A visionary with heart

In his youth, Dr. Robert Bryant never imagined he’d one day become a NASA scientist with an abundance of patents and awards. But thanks to the combination of his personal ethics, willful self-determination, and an encouraging word from an educator, Bryant went on to exceed his own expectations, develop technology for life-saving equipment, and has been inducted into the 2023 class of the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

15 min read

Each month, our Journeys of Innovation series tells the stories of inventors or entrepreneurs who have made a positive difference in the world. This month, Candace Mundt-Bates's story focuses on Dr. Robert Bryant, a NASA scientist who discovered a unique polymer that would go on to change the lives of heart patients around the world and lead to his induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Do you know an innovator or entrepreneur with an interesting story?

“Don't tie your destiny to anybody else except yourself,” said NASA scientist Robert Bryant, sitting in his wood-paneled office at the NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, as fighter jet engines roared in the background.

That doesn’t mean to be uncooperative or to isolate yourself, Bryant clarified.

“What that means is develop your skills, use them to the point where others appreciate what you're doing, but never tie your destiny to somebody else because you're turning over your self-worth to these other people,” he added.

Evidence of this point of view can be found next to Bryant’s office front door: a depiction of a rōnin. In feudal Japan, rōnin were wandering, masterless samurai who put their military knowledge and swordsmanship to use as independent mercenaries and guards.

Rōnin, an offshoot of the famous samurai of feudal Japan, were controversial figures during that time, but NASA scientist Robert Bryant said he admires their insistence on independence and self-determination. The term is written using two Japanese characters: "floating" and "man."

(Jay Premack/USPTO)

He chose that drawing because he admires the rōnin’s persistence to become the master of their own destiny, he said.

Using his unique outlook, Bryant has made a career of determining his own destiny despite professional and personal hurdles and has positively impacted millions of people with his innovative solutions to modern-day problems. He has more than 30 patents and peer-reviewed journal articles and has written more than 100 technical papers ranging from small and lightweight power amplifiers to magnetic and mechanical properties of molded iron particle cores.

It was Bryant’s perspective on a special polymer that would move its use from the troposphere to inside the human body.

In the 1990s, while conducting research for NASA’s High Speed Civil Transport (HSCT) project — think an American version of the British Concorde supersonic airliner — Bryant noticed that an experimental polymer behaved abnormally: despite being exposed to extreme temperatures, it remained soluble when it should have precipitated into a powder, which was completely unexpected for this class of polymers. After repeated successful experiments, the Langley Research Center-Soluble Imide (LaRC-SI) was born. This polymer is a durable and flexible thermoplastic that can be fabricated into very thin films and coatings, molded into solid objects, and is biologically non-reactive and solvent resistant.

At that time, he said his leadership didn’t see its use for HSCT when compared to the many other polymers screened for the aircraft and was thus not chosen for the project.

But Bryant knew this polymer had potential, even if others couldn’t see it.

“I had a particular technology that I thought was extremely good in the many ways it could be processed, but I wasn't running the show,” he said.

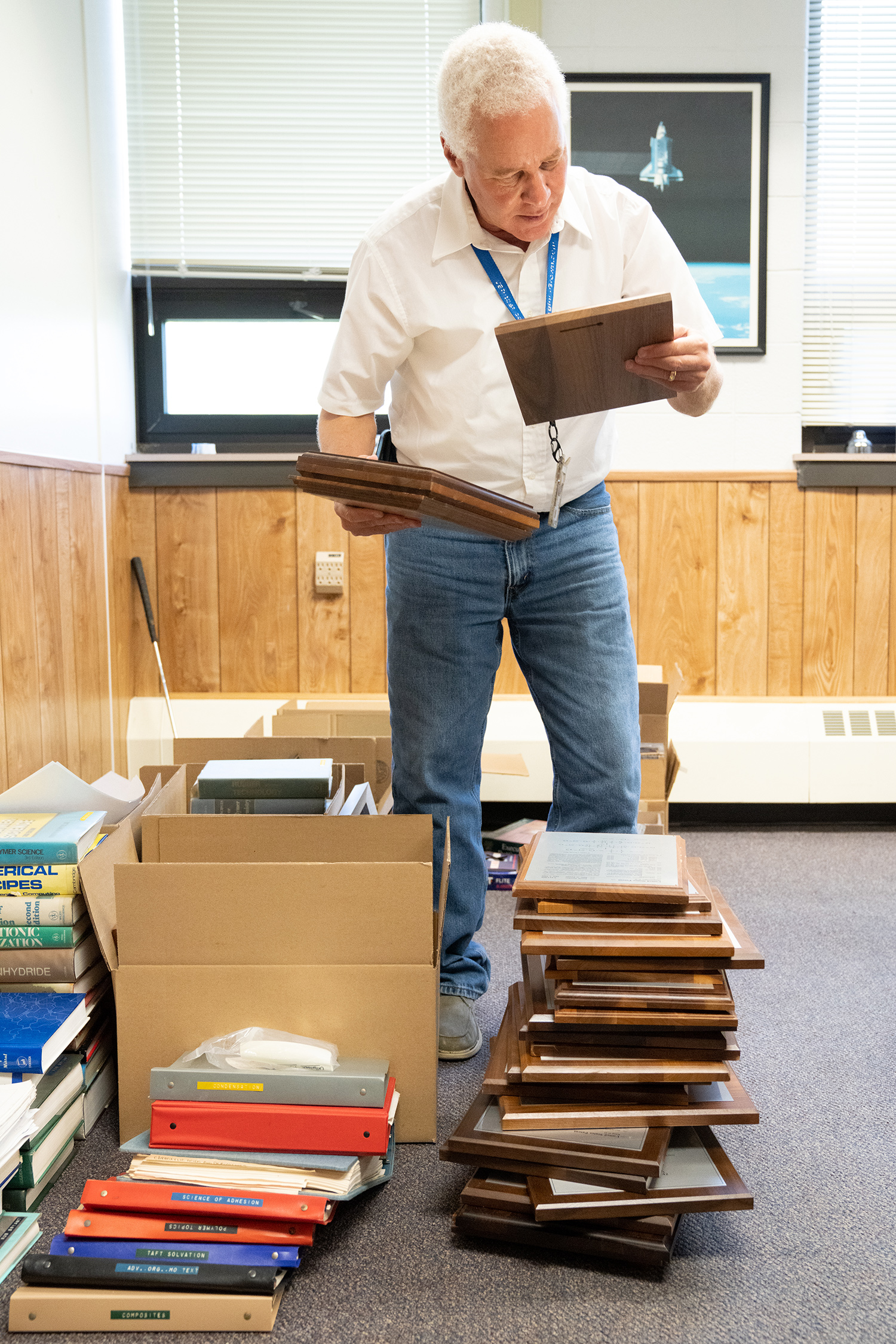

Over his three decade career, Robert Bryant has been awarded more than 30 patents. Here he peruses his commemorative patent plaques that are stacked knee-high in his office at the NASA Langley Research Center in Virginia.

(Jay Premack/USPTO)

During this period, the federal government worked to incentivize manufacturers in the United States to start producing specialty chemicals important to NASA’s research that were previously sourced from foreign countries. The objective of this shift was to enable the agency’s scientists to fine-tune the formulas and methods for developing materials on a small scale, so companies could commercialize products more efficiently.

Bryant believed his new technology could meet part of this strategic need.

Despite pushback from colleagues and leadership due to manpower needed for the original HSCT project, he forged ahead by securing discretionary funding that would allow him and his team to work independently on LaRC-SI.

After pouring countless hours and funding into creating the LaRC-SI polymer, Bryant was determined to see it go to market and prove its value. This was especially important to him as his work was financed by the American taxpayer, a fact that motivated Bryant to find ways for his work to be utilized, even if the trajectory of the project shifted drastically.

“When you start something, you gotta finish it – that was my attitude,” he said.

The team would find success in the medical device market, and its value for countless patients would be priceless.

Bryant recalled the medical industry seeing his research team’s strict test protocols for their polymer as a form of risk reduction. They seized on the opportunity to test it for their own pacemaker technology. Due to its thin, flexible, and biologically non-reactive properties, the thermoplastic is ideal to use as insulation around the wires that are used to control the pacemaker. After the polymer was approved in Europe, rigorously tested and improved for its new medical use, it also received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2010.

Since then, more than half a million heart patients have benefited from the technology.

Bryant’s ability to envision what others cannot has been aided by his perseverance in overcoming the literal visual limitations imposed by oculocutaneous albinism type 2, a genetic condition of the eyes. It wasn’t until he was in his 40s that he received an official diagnosis from an optometrist.

“From being a little kid, all the way up until then, I had no idea,” he said. “I think everybody has heard the term ‘wobbly eyes.’ You run across somebody whose eyes shake – that’s what mine do.”

Bryant describes the visual limitation as like seeing the world in two dimensions rather than three dimensions, also known as monocular vision.

“For me, the world is like if you go to a movie theater. I look at the world – I’m not in the world.”

The condition had an enormous impact on Bryant’s school years and childhood.

“School was horrible for me,” he said. “I would just ignore everything or poke the kid next to me. I wasn’t paying attention because there’s nothing to pay attention to when you can’t see.”

Despite lacking interest, Bryant never failed to turn in an assignment regardless of how bad the grade might be.

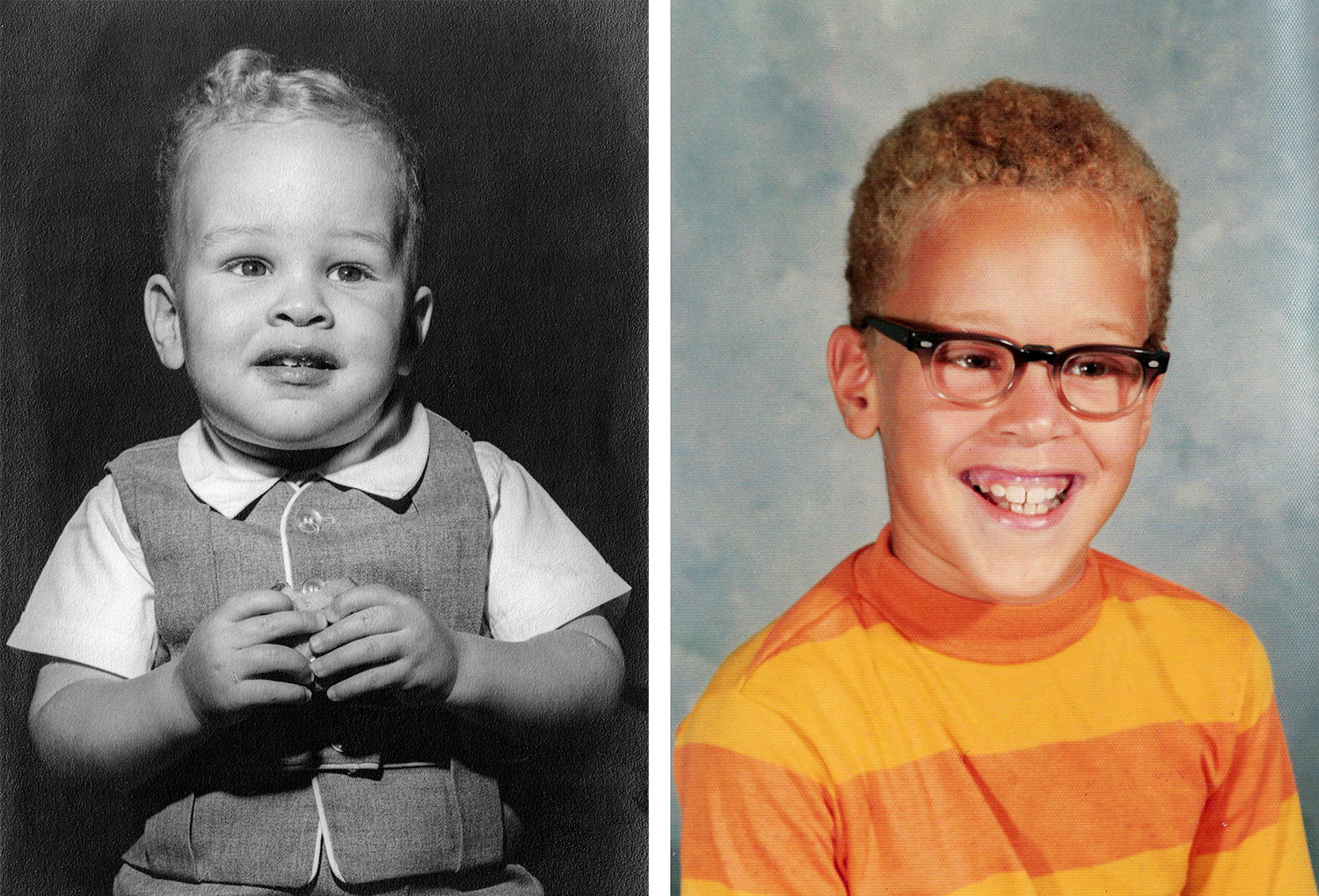

At left, Robert Bryant at 2 years old posing for a photo with a cookie that his mother said she had to give him so he would cooperate. On the right, Bryant at 9 years old, posing for a school photo, now with glasses. He described himself in his younger years as a “bad student” who passed time in class by being disruptive since he couldn’t see what he was supposed to be learning.

(Photos courtesy of Robert Bryant)

“If you say you’re going to do it, do it,” he said, relating that he routinely witnessed his parents – a university professor and a librarian – follow through on difficult tasks.

Outside of school, Bryant’s condition also impacted his ability to enjoy many childhood traditions. Sports involving balls and other activities that required depth perception were a no-go. Instead, he turned to building LEGO sets, taking apart and putting back together different items around the house, and spending time in nature.

While his report card was less than impressive, he did have one remarkable accomplishment in his youth – becoming an Eagle Scout.

“As a scout, I always liked being outdoors and doing all these different physical types of activities,” Bryant said. “It takes a long time to become an Eagle Scout, usually about four or five years in general, so you have a lot of opportunities to quit. I’m not going to kid around, some of it was sort of a pain in the behind, but when you’ve already run 90 yards of a 100-yard race, there’s a lot of pain you can put up with in that last 10 yards.”

Beyond the new rank and praise, Bryant noted that when he became an Eagle Scout, younger scouts started looking up to him.

“You get all kinds of nice things and recognition, but I think the real point of it is that the younger ones that you have led as you’ve gone up through the ranks see what you go through,” he said. “It inspires them to do the same thing, because they realize that they can do it too.”

Bryant applies the work ethic he honed through adolescent experiences like scouting to his preferred physical aspects of science. He continues to favor tinkering and work that is hands-on over tackling formulas and theories and said he considers himself in that middle area between the farmer, where the pigs are raised, and the market, where the sausage is sold.

“I am focusing on the side of the manufacturer, the stuff that gets under your fingernails,” he said. “No one can computationally model themselves out of having a heart attack. You’ve gotta have surgeons, and you’ve gotta have the tools, and somebody has to make them.”

A NASA research intern prepares to seal a panel so it can be tested under specific temperature and pressure settings. These panels may be used as a part for aircraft, spacecraft, and test specimens.

(Jay Premack/USPTO)

After more than three decades of tinkering, Bryant has now transitioned into more of a mentorship role at Langley, tasked with inspiring future innovators at NASA and beyond. His day-to-day work now includes regularly interacting with and providing guidance to interns and employees on apprenticeships. One of the main lessons he tries to teach is to not waste time by repeating the mistakes of those who came before you.

Bryant recalled an interaction with a former student that spoke to this notion.

After providing the student instructions for an experiment, Bryant predicted the student’s meandering pathway toward success. The first attempt wouldn’t work because he wouldn’t follow the directions; the second effort would fail because he’d try to find a shortcut; the third time, the student would follow the directions to show how the experiment wouldn’t have worked even with Bryant’s instructions. That time, the student found success... and humility.

After the student admitted to the missteps, Bryant chuckled and provided some perspective.

“You have no idea how many times I actually performed this experiment... before it actually worked,” he said at the time, acknowledging his own difficult path to finding the right recipe for success.

This summer at Poquoson Elementary in the Norfolk area of Virginia, Bryant continued his work with students, but this group was considerably younger.

In June, he shared his passion for invention with future innovators at Camp Invention, a STEM summer camp program for K-6 students coordinated by the National Inventors Hall of Fame (NIHF) in partnership with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, and hosted by schools across the country. Campers learned about biomimicry and genetics, designed and engineered their own mini skate parks, built a musical instrument, and explored intellectual property and business strategy ideas.

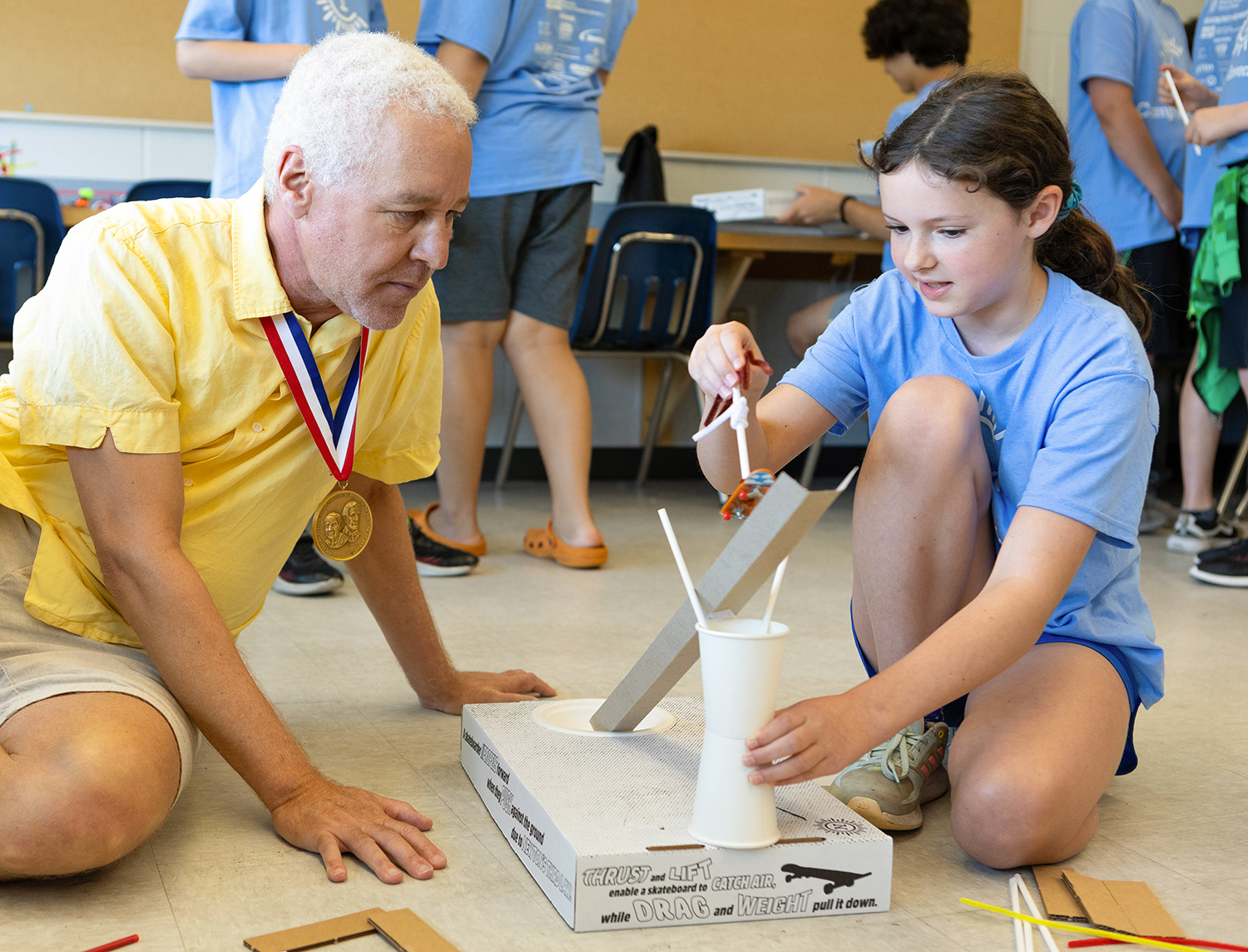

A young Camp Invention participant shows NASA scientist Robert Bryant her mini finger-board skate park that she designed, engineered, and built. Activities like these help campers learn about physics, invention, and the art of design.

(Courtesy of Debbie Leanne Portraits)

During his visit with campers, Bryant focused on instilling a practice of writing, drawing, and journaling – because it’s easier to change a drawing than something you’ve built.

“There's something about writing that connects your thoughts and focuses them on what you're doing. And when you lie to yourself on pencil and paper, which you will do because you are a human, you'll cross it out. You’ll say, ‘no, that's not what I mean,’ and it helps you really focus and get through things,” he said, adding that he was inspired to start journaling by his own daughter.

Bryant observed that the students at Camp Invention were completely engaged in the interactive learning process and motivated to do the work without regular assignments like book reports. Reflecting on his own independent path in science, he noted that the students were encouraged to work through their projects because they were able to understand the importance of the process and weren’t limited to strict parameters along the way.

“They were all doing their own thing, and there wasn't a wrong way to do anything," he said. “What I've seen with this program is that really helps the kids a lot in terms of self-esteem [and coming up with their own] ideas.”

Although Camp Invention didn’t exist when Bryant was in school, he did receive the self-esteem boost he needed from one memorable professor while completing undergraduate courses at Valparaiso University in Indiana with an undecided major.

The encounter came after he determinedly studied for the American Chemical Society Organic Chemistry Test and received one of the highest scores in the country and top grades in his class. In a speech he gave at Valparaiso in 2022, Bryant said he studied for this test out of anger because he found out that other students would go up to the professor after taking quizzes and tests and try to negotiate for a better grade – a thought that never occurred to him, as he considered it cheating. He said this made him want to show them all up.

After unexpectedly excelling at the test, Bryant was encouraged by the class instructor, Professor Gilbert Cooke, to pursue a career in chemistry.

“He was probably one of the first people who ever came up to me and said, ‘you’ve got some sort of talent,’” Bryant shared. “That helped me put a lot more effort into [school], because even if you’re doing well all the time, if nobody says anything, you really don’t know. So, you do have to get recognition every once in a while from somebody who is an expert in that particular area.”

Replicating that positive experience, Bryant routinely motivates the people on his teams in the test lab, taking time to talk through problems and by ensuring they receive credit for their work.

“A lot of the publications that I have and the patents, most of them [list] more than me because I make sure that people get credit or acknowledgement for what they do,” he said. “I think that really helps them, especially when they’re working hard, and they see their work being reflected in something other than ‘thank you.’”

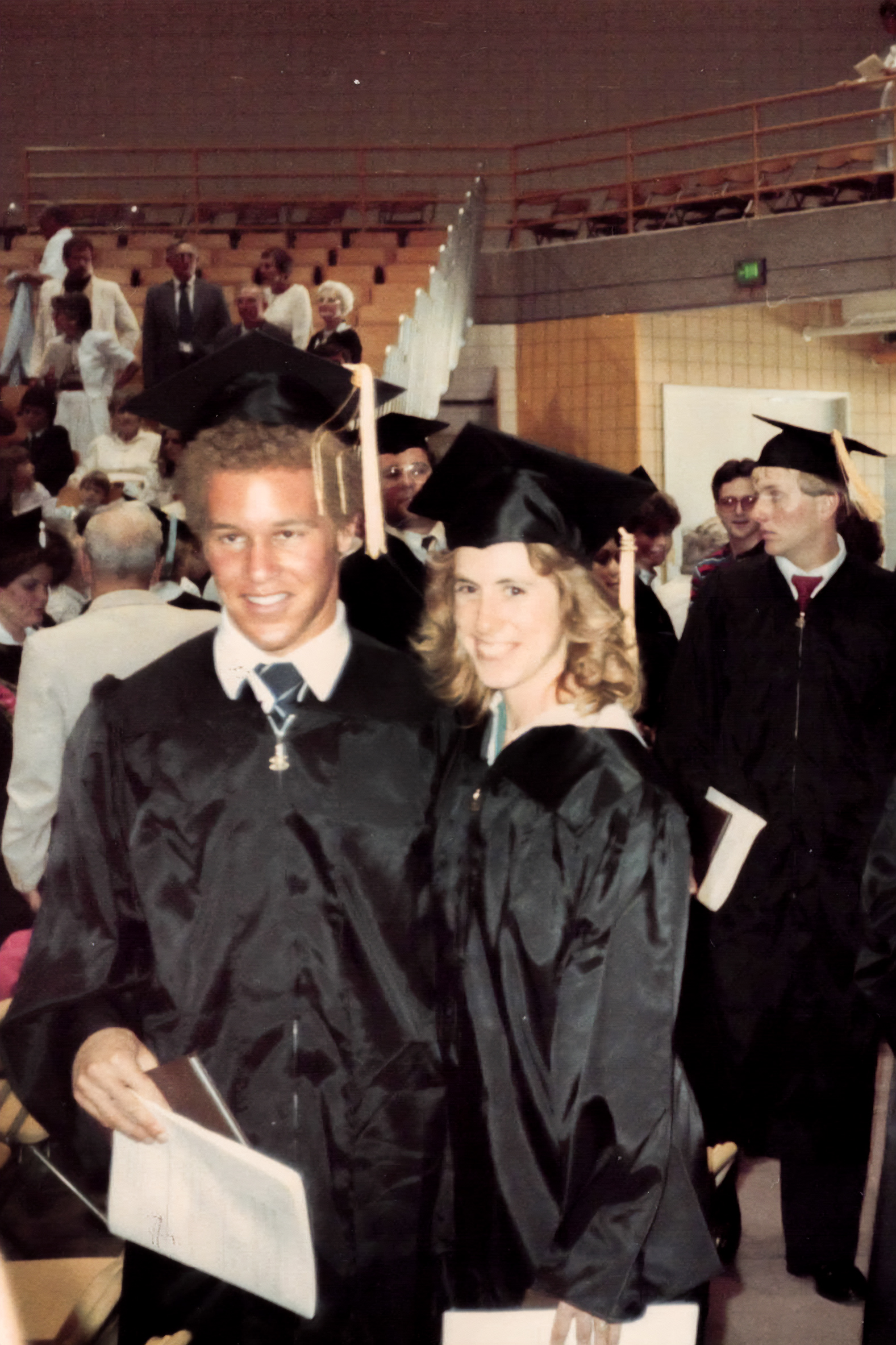

Robert Bryant, left, with his future wife, Joy, at their college graduation ceremony at Valparaiso University in Indiana. Both chemists, each has left their mark in innovation- Robert as an inventor and Joy as a patent attorney and author of "Protecting Your Ideas: The Inventor's Guide to Patents" which helps readers understand the patent process.

(Courtesy of Robert Bryant)

Outside of the test lab, Bryant himself credits one person specifically for helping him achieve his many accolades: his wife, Joy.

Not only was she the one who told Bryant why students were going up to the professor after class – the catalyst that led him to study so hard for the test that would propel his professional career – she is also a patent attorney who has routinely helped him through the process of protecting his intellectual property.

Joy was a freshman, and he was a sophomore when they met. Bryant recalled that they didn’t particularly like one another at first, but she was dating his best friend, and they were both studying chemistry, so they crossed paths regularly. Eventually, the pair bonded, and they started dating. Bryant clarified that there was no issue with the best friend, who was part of their wedding.

Upon deciding to start a family, Joy moved out of the laboratory to focus on intellectual property at the College of William and Mary, earned her law degree on a patent agent track program, and became the patent attorney for many of Bryant's patents.

He said that Joy’s background allows her to understand what he’s created and how or if it is patentable.

“She has a saying that has turned out to be extremely true… she says inventors very often don't know what they've invented,” Bryant said, giving an example of an inventor thinking they invented a doorknob, but for patenting purposes and constructing claims, it is really a type of handle.

Joy’s unique perspective has pulled him out of a sort of tunnel vision he has when thinking of the things he’s invented and has empowered him to focus more on the claims that are required for patentability, he added.

In addition to sharing a love for chemistry, they both naturally have a passion for cooking, which Bryant quipped is chemistry that you’re allowed to eat.

“I’m always going to say my wife [is the better cook] because I have a feeling that she’s going to see this one day,” he joked. “I’m more of the meat cook. She’s more of the everything else cook. That’s how we keep out of each other's hair.”

No doubt in part thanks to the ongoing professional and loving support of his wife, Bryant has had a momentous career that continues to reach new heights. He’s been inducted into the NASA Inventors Hall of Fame and the Space Foundation’s Space Technology Hall of Fame, and in October of 2023 he will be officially inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame (NIHF) – which is celebrating its 50th anniversary. He humbly acknowledged his place among more than 600 inventors who have made history with their work.

“I think it’s one of the highest recognitions for inventors,” Bryant said. “It’s just a very wonderful place to be. I know all these people have had their own particular stories… and I think it’s a very relatable group, so I’m very honored to be a member of it.”

Despite all his successes, Bryant still sees himself as moving across stumbling blocks. He said he still has trouble reading the fine print in his textbooks. He pointed to a magnifying glass that aids him when his glasses are no longer enough.

“The struggles are still there, but you know everybody has struggles,” he said. “Mine are always larger in my own eyes, but they're not larger in the context of everything.”

“People have all kinds of things they’re always overcoming. I figure I’m one of the many, not one of the few."

Robert Bryant pauses briefly during a tour of Langley’s Measurement Systems Laboratory (MSL) a state-of-the-art research facility for developing, testing, and implementing new sensor technologies.

(Jay Premack/USPTO)

Credits

Produced by the USPTO’s Office of the Chief Communications Officer. For feedback or questions, please contact inventorstories@uspto.gov.

Story by Candace Mundt-Bates. Additional contributions from Whitney Pandil-Eaton, Jay Premack, Eric Atkisson, Jon Abboud, and Jennifer McIntosh. Special thanks to Robert Bryant, David Meade, Rini Paiva, Gregory Lovas, and the staffs at NASA and the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

References

Bryant, Robert. Interview by Candace Mundt-Bates. June 15, 2023.

Bryant, Robert. Interview by Candace Mundt-Bates. July 7, 2023.

“Camp Invention.” National Inventors Hall of Fame. https://www.invent.org/programs/camp-invention

“Robert Bryant.” ReasearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Robert-Bryant-11

“Robert Bryant: LaRC-SI (Langley Research Center-Soluble Imide).” National Inventors Hall of Fame. https://www.invent.org/inductees/robert-bryant

Valparaiso University Career & Alumni Network. “My Valpo Story: Robert Bryant ’85, ’19H.” YouTube video, 1:18:29. October 29, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IaI9KE6EUjA&t=72s