Artificial intelligence for all

Beyond the buzzwords and hype about artificial intelligence (AI), scientist Natalia Bilenko works to develop AI tools that are transparent and usable for everyday people.

She focuses on capturing and codifying human knowledge by collaborating with scientists and individuals from a variety of backgrounds and aims to advance AI without replicating human biases and stereotypes.

12 min read

Each month, our Journeys of Innovation series tells the stories of inventors or entrepreneurs who have made a positive difference in the world. This month, we focus on scientist Natalia Bilenko's journey.

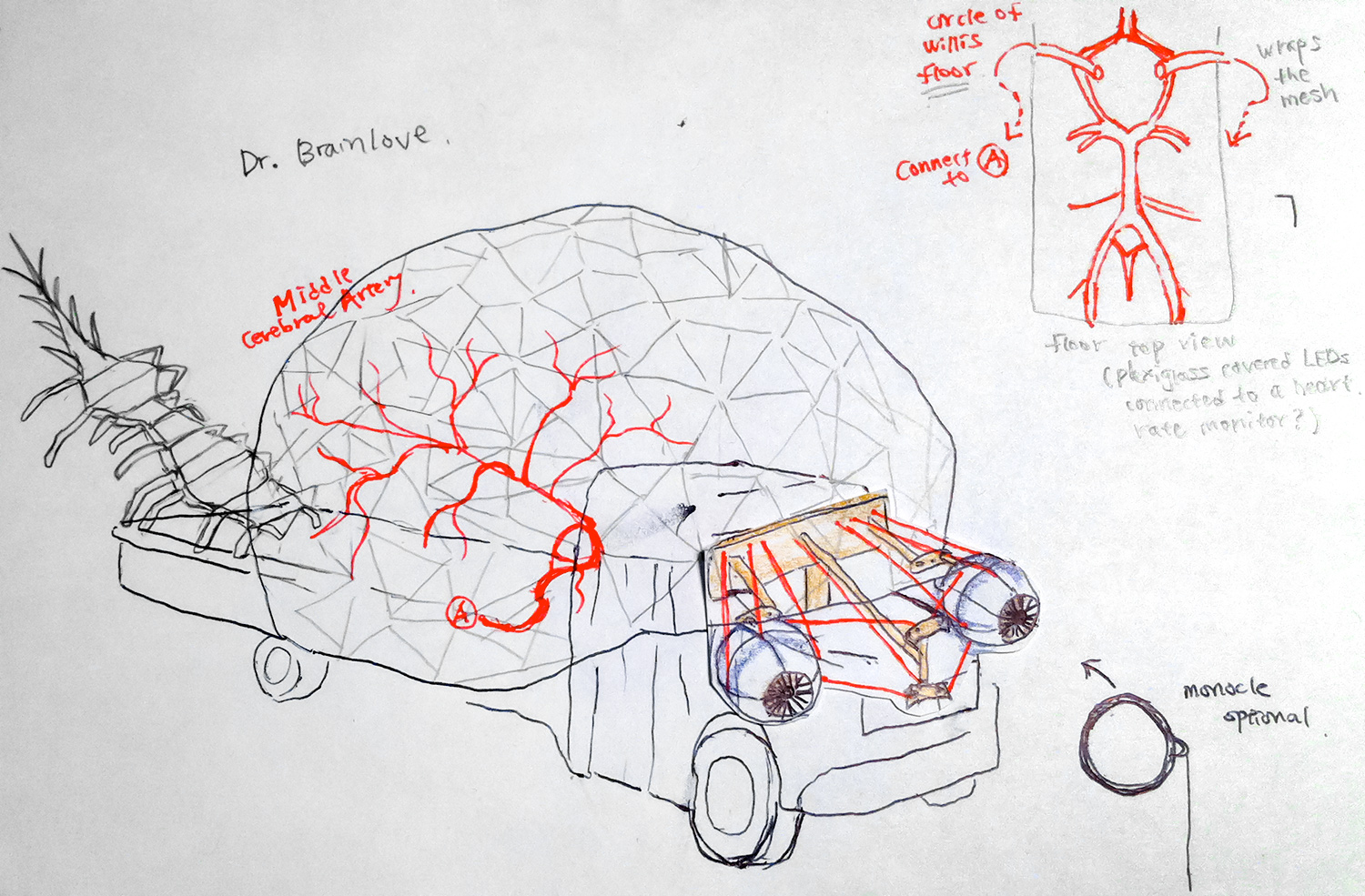

Out in the darkness of the Nevada desert, people clamber over a silver metal structure as it lights up the night with flashing multi-colored lights. It’s part rave and part science exhibit, a school-bus-sized feat of engineering glowing on the dusty playa. Called Dr. Brainlove, it’s one of the art cars of the Burning Man Festival, a drivable, surrealist piece created specifically for this yearly event focused on community, art, and self-expression. Even at a distance, the geometric jungle gym structure quite clearly resembles a human brain. The Atlantic magazine called Dr. Brainlove “the most Burning Man thing ever,” even more so than the soaring wooden "temples" that spring up overnight in the desert only to be purposely lit on fire, the temporary semicircular encampment lined with streets called “freak show” and “hanky panky,” or attendees cosplaying as aliens, faeries, and cyberpunks.

Dr. Brainlove rolls through the desert at Burning Man. (Photo courtesy of Tom Bishop)

An early sketch of Dr. Brainlove drawn by Asako Miyakawa. (Image courtesy of Asako Miyakawa)

But Dr. Brainlove is more than a colorful addition to a far-out festival. It aims to stop attendees in their tracks, encourages them to consider how their own brains constantly process information, and hopefully inspires them to learn more about neuroscience. The actual brain behind Dr. Brainlove belongs to scientist Natalia Bilenko, who volunteered her own MRI brain scans to the project team of over 100 scientists, engineers, and artists that created this rolling art installation.

“Thinking about art as a medium for communication of technology and making technology more accessible, that has always appealed to me,” says Bilenko.

In addition to the large but not exactly street-legal Dr. Brainlove vehicle, she helped engineer a smaller four-foot version, called “MiniBrainlove,” which debuted at the Bay Area Science Festival in 2014, and brought a tabletop version (“MicroBrainlove”) to the SXSW festival in Austin, Texas. Bilenko says these efforts are all about encouraging community engagement and participation at the intersection of art and science.

She also co-created an exhibit for the San Francisco Exploratorium called Cognitive Technologies, the world's first interactive exhibit to use real-time brain activity. The interdisciplinary project brought together artists and scientists to create an environment for the public that would demystify the “black box” of what’s happening in the human brain. Visitors experimented with cutting-edge scientific tools to understand and extend the human mind. Attendees could use hand gestures to explore a 3D model of a brain created from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data, or they could don an electroencephalography (EEG) cap and control a mechanical arm using only their mind. “I can’t help but feel like I’ve just watched magic happen,” wrote a reporter who visited the exhibit.

Bilenko (left) and exhibit co-creator James Gao (right) demonstrate how visitors could interact with their exhibit at the Cognitive Technologies exhibit at the San Francisco Exploratorium. Attendees could use gestures to explore the data on the screen. (Photo courtesy of Anja Ulfeldt and the Cognitive Tech group)

Bilenko examines a prototype of Dr. Brainlove, an interactive art car modeled on scans of her own brain. (Photo courtesy of Asako Miyakawa)

The desire to understand unseen processes has always interested Bilenko. As a child, she was fascinated with chemistry and studied chemical formulas to better understand what was occurring inside living organisms and in the natural world around her. When she was a teenager, she emigrated from Russia to the United States with her parents and had to navigate the usual challenges of high school while also adapting to a new country and culture. Although she had studied English in school in Russia, “there was discomfort with spoken language that took a while to get over,” she says. Around that time, she became interested in language processing and neuroscience as she noticed that formulas and models could not explain everything she experienced and observed.

“What jumps to mind is this word 'ambiguity,'” she says.

In college at Brown University, she worked in a neural linguistics lab, studying how the brain interprets ambiguous words like “stable,” which can mean either a shelter for horses or a description of something that doesn't change.

“That was the seed for me: thinking about how language is a model of the world, and we have different ways of understanding.” But, she quickly points out, “the problem with models is that they are static representations. The world is not as simple as any model, and it’s constantly changing.”

Natalia Bilenko (far left) moderates a discussion with panelists Morgan Klaus Scheuerman (speaking), Hannah Wallach (right), and Vivienne Ming (far right) discuss “Algorithmic inequity and the impacts on the queer community and beyond.” (Photo courtesy of Raphael Gontijo Lopes )

Her interest in mental models led her to the field of artificial intelligence (AI), which seeks to train computers to create models that make meaning from information and draw conclusions as effectively as humans. For decades, computers were limited to performing simple tasks with clear rules. Computers struggled to interpret new types of data, and they were easily derailed by ambiguous information or items that fit into several categories. Advances in AI aim to change this, allowing computers to provide ever more sophisticated data back to humans. One of the most difficult challenges in AI is computer vision – a subfield of artificial intelligence that trains computers to identify and recognize people and objects. For example, a computer can be trained to recognize that two photographs – one showing a person with a beard and long hair, the other showing a person with no beard and short hair — are in fact, both images of humans.

“I tend to find my personal and professional interests in the spaces between art and technology. Identifying as queer is part of that,” says Bilenko, who identifies as queer and non-binary. “Also being an immigrant, that is part of my experience as well -- being in that in-between place.”

Bilenko (center, with microphone) explains the MicoBrainlove art piece to interviewer Mario Milicevic at a SXSW event in Austin, Texas. (Courtesy of IEEE)

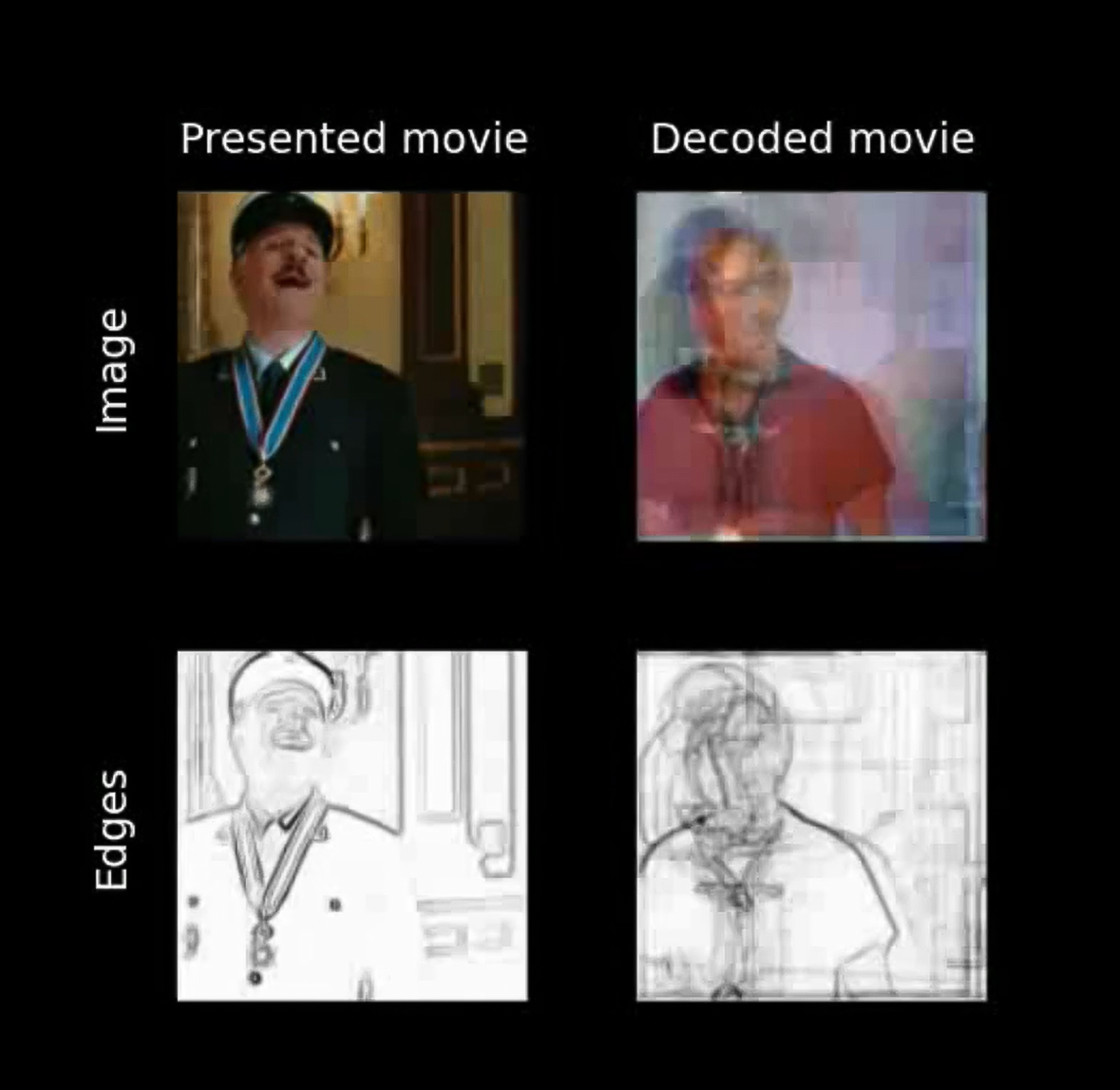

Bilenko, Valkyrie Savage, and Berkeley Professor Jack Gallant built off of earlier work in computer vision to train artificial intelligence algorithms to reconstruct images that participants had seen, based on what areas of their brains were activated. Although blurry and imperfect, the images the AI produced were surprisingly close to the original images.

As a graduate student in neuroscience at the University of California at Berkeley, Bilenko met students Asako Miyakawa and James Gao, who would become co-creators of Dr. Brainlove and the Cognitive Technologies exhibit. She became a researcher in Professor Jack Gallant’s lab, collaborating with him on a project to train a computer to reconstruct a person’s visual experience by interpreting EEG signals from the brain. The researchers created a computer algorithm that could interpret the brain impulses, match them against visuals collected from thousands of hours of YouTube videos, and generate movies that illustrate likely images based on the impulses.

To outside observers, the results looked freakishly like computer-assisted mind reading. While the resulting visualizations were hazy, the work made a big splash in the tech community. It even prompted Mark Zuckerberg to declare that in the future “you’re going to be able to capture a thought.” With his usual techno-optimism, Facebook’s founder envisioned a time when “what you’re thinking or feeling in its ideal and perfect form in your head, [you will] be able to share that with the world in a format where [others can] get that.”

Bilenko herself takes a much more pragmatic view: “the mind leaps very quickly to what it could be, but there are a lot of uncomfortable possible possibilities as well,” she says. She is quick to point out that the visually striking findings came from participants who consented to hours and hours of research, and that everyone’s brain is different, so the brain decoding only works if it has been calibrated to each person individually.

"There are some grand ideas about what AI could be in the future, and it's important for technologists like me to think about the impacts and repercussions of our work,” she says.

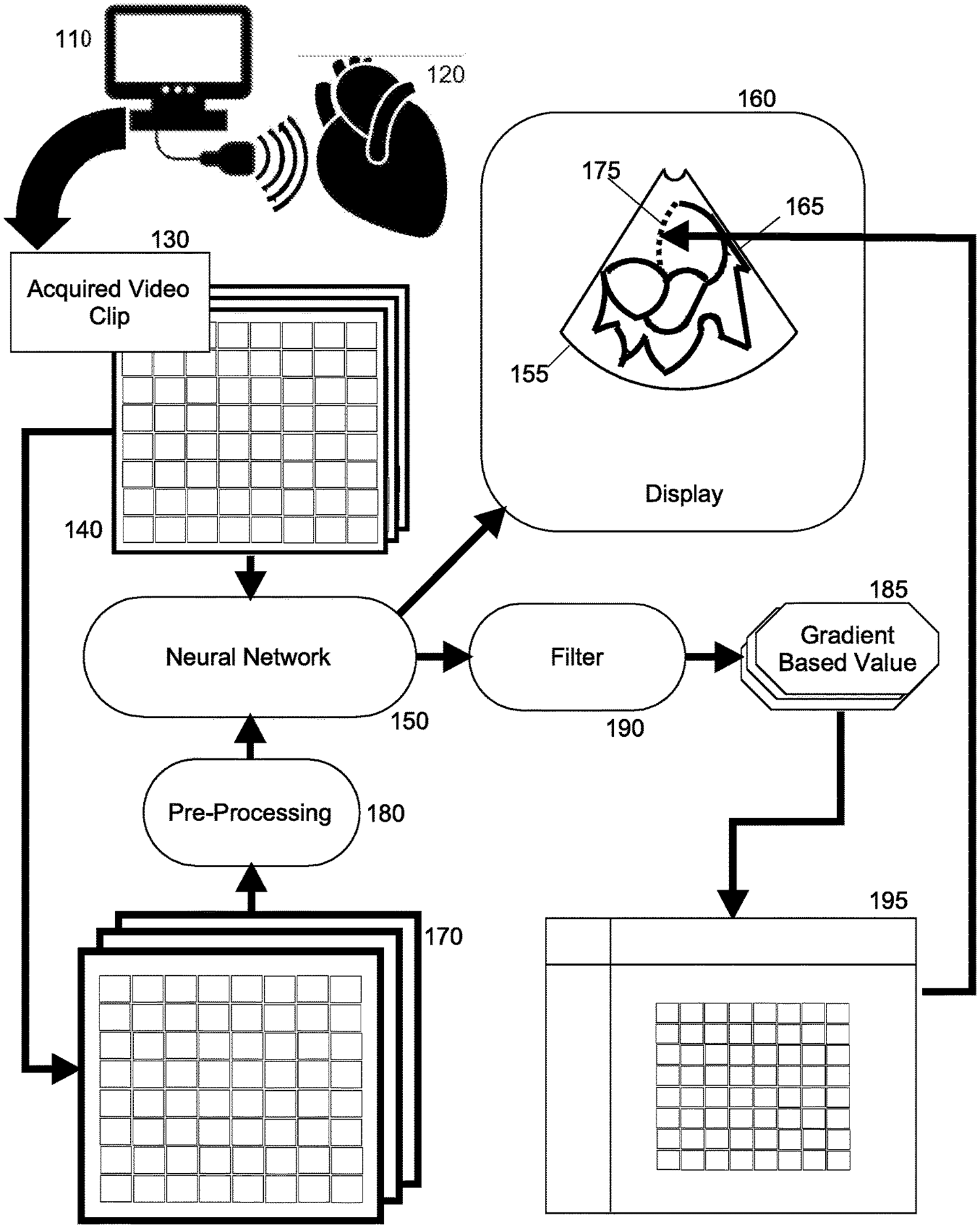

After graduating from Berkeley, Bilenko turned her AI skills to a more pressing present-day concern: better screening for heart problems. Moving from the academic lab into industry was important to Bilenko because private companies tend to focus on bringing the immediate, practical applications of new technologies to market. Having been exposed early to science and medicine thanks to her grandfathers – one was an inventor and professor of nanoelectronics, the other a surgeon – her new job drew on her interest in artificial intelligence, healthcare, and innovation. She joined an eight-person medical device company called Bay Labs (now known as Caption Health), which employs AI to make ultrasound scanners easier to use.

Drawing from U.S. Patent no. 1,093,7156 for "Saliency mapping of imagery during artificially intelligent image classification," co-invented by Bilenko and her colleagues when she worked at Caption Health.

“Ultrasound-based imaging is really important for early detection,” says Bilenko. “But because people have to be highly trained to use the technology, it’s really costly, and it’s often a problem to get the proper checkups and diagnosis.”

The team of engineers at the company met with experienced medical professionals to understand what the experts look for when scanning the heart for problems. They fed the computers reams of visual data from different machines, both clear images and very poor ones.

They trained the computers to assess the visuals from the scanners, created an interface that gave real-time guidance to operators on positioning the scanner and confirming if the image captured was clear, and developed a method to sift through the thousands of images captured during the hour-long exam to identify the best ones for medical specialists to review.

This new technology could help catch heart problems early and could be particularly impactful for people who live in rural areas far away from experienced cardiologists and ultrasound technicians.

“The goal was to create a tool so someone who was not necessarily a fully trained tech could do a checkup that might indicate if a patient should be redirected to a professional, similar to taking your blood pressure,” says Bilenko.

The research resulted in three patents for Bilenko and her co-inventors, and the Caption Health AI-guided scanner was named one of the “100 Best Inventions of 2021” by Time Magazine. With heart disease being the leading cause of death in the United States, the work is both cutting edge and potentially lifesaving. Her research also led to two more patents on related technologies, making her a named inventor on five patents before the age of 37.

Caption Health's cardiac scanner uses AI to provide real-time feedback to the scanning technician on the quality of the images being collected. The yellow and green indicators in the top left of the scanning screen help technicians confirm they are capturing clear and useful images. (Photo courtesy of Caption Health)

As a visible role model in the AI community and an organizer of Queer in AI, Bilenko works to ensure the field welcomes all scientists to contribute their ideas and perspectives. (Photo courtesy of Rachel Kalmar)

“I think that a lot of my approach to working with technology is motivated by how to avoid the non-benevolent uses of technology. And there can be a lot of dangers to AI in particular.”

The lack of diversity among AI practitioners is a known challenge. Another is the absence of participation and input from those outside the field who might be affected by the technology. While Bilenko’s short purple pixie haircut wasn’t particularly notable amongst the diverse team that brought Dr. Brainlove to Burning Man, it did cause her to stand out when she attended scientific conferences.

“AI is a profession that excludes a lot of people from participating, and that’s a huge problem,” she says. Chatting with a handful of non-binary and queer scientists among the thousands attending a key research conference in the field, they brainstormed how to address these issues. The result was “Queer in AI,” a group to support queer researchers and raise awareness of issues in AI and machine learning that might disproportionately affect the queer community. They took their inspiration from other newly created groups like Women in AI (founded in 2016) and Black in AI (founded in 2017).

“A lot of the motivation I had for starting the organization Queer in AI with other folks, it was about some of these impacts of technology on people who are marginalized – both in society in general and in access to these technologies.”

Queer in AI found that most queer scientists they surveyed do not feel completely welcome in the field, partially due to a lack of a visible community and role models. Since then, Queer in AI members have worked to become a more visible presence in the larger AI community, returning to that conference and others each year to host social gatherings, lead mentoring sessions, and give research talks. The group has created a scholarship fund to help students apply to graduate school in AI and worked to raise awareness of concerns within the queer sub-community of the larger AI community. Through their original research and advocacy, they encourage and highlight new findings to address various concerns, such as the ethical use of AI, privacy and safety, and how binary-based model assumptions can harm members of the queer community. Bilenko notes that algorithm development requires a large volume of data, and sometimes older data includes assumptions based on stereotypes, which then reinforces biased decision making.

“It’s not just wrong, but wrong in ways that harm those that are already the most marginalized.”

Queer in AI organizers, from left to right: Raphael Gontijo Lopes, William Agnew, and Natalia Bilenko prepare materials for the Queer in AI workshop at the 2019 NeurIPS Conference.

The group organizes community building activities and workshops, and provides scholarships for students interested in graduate work in artificial intelligence. (Photo courtesy of Raphael Gontijo Lopes)

Through art cars, public exhibits, inventing new medical tools, and now advocacy, Bilenko has worked to bring others into the process of technology development and meaning-making. She views others, including people who provided the personal data that informs the models, as co-creators in an AI-augmented future. She is particularly inspired by concepts such as design justice, which lays out a vision to make marginalized communities central in the development of new technologies, helping to dismantle structural inequality. With experience developing creative ways for non-scientists to explore and understand how AI works, “there’s a way design can be participatory and people can participate in work that may affect them later on.”

“The technologies are not really separate from the politics and environment in which they are created,” says Bilenko, making it all-important that everyone is given opportunities to help co-create the future of AI.

Credits

Produced by the USPTO’s Office of the Chief Communications Officer. For feedback or questions, please contact inventorstories@uspto.gov.

Story by Laura Larrimore. Contributions from Megan Miller, Rebekah Oakes, and Eric Atkisson. Special thanks to Natalia Bilenko, Tom Bishop, the staff at IEEE, Rachel Kalmar, Raphael Gontijo Lopes, Asako Miyakawa, and Anja Ulfeldt.

The photo at the top of this page shows Bilenko assembling the metal struts and sensors that form Dr.Brainlove. Photo courtesy of Rachel Kalmar.

References

Bos, Sascha. "This is Your Brain on Science." East Bay Express. February, 18, 2015. https://eastbayexpress.com/this-is-your-brain-on-science-1/.

Black in AI. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://blackinai.github.io/#/.

“Caption AI Product Demo | AI-Guided Ultrasound System.” Caption Health. YouTube video, 1:45, April 19, 2021. https://youtu.be/URmb72IA4b4.

Cognitive Technologies. Accessed May 31, 2022. http://www.explorecogtech.com/.

Costanza-Chock, Sasha. Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. Boston: MIT Press, 2020.

Dr.Brainlove. Accessed May 31, 2022. http://www.drbrainlove.org/.

Gallant, Jack, Natalia Bilenko, Valkyrie Savage. “Using Image Processing to Improve Reconstruction of Movies from Brain Activity.” Vimeo video, 1:30. June 7, 2016. https://vimeo.com/169779284.

LaFrance, Adrienne. “The Most Burning Man Thing Ever.” The Atlantic, July 14, 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/07/colossal-brain-s….

Queer in AI. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://sites.google.com/view/queer-in-ai/.

“The Best Inventions of 2021: Sonograms Made Simpler | Caption AI,” Time Magazine. November 10, 2021. https://time.com/collection/best-inventions-2021/6112557/caption-ai/.

Women in AI. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://www.womeninai.co/.