Beyond Baker’s list: Black innovation then and now

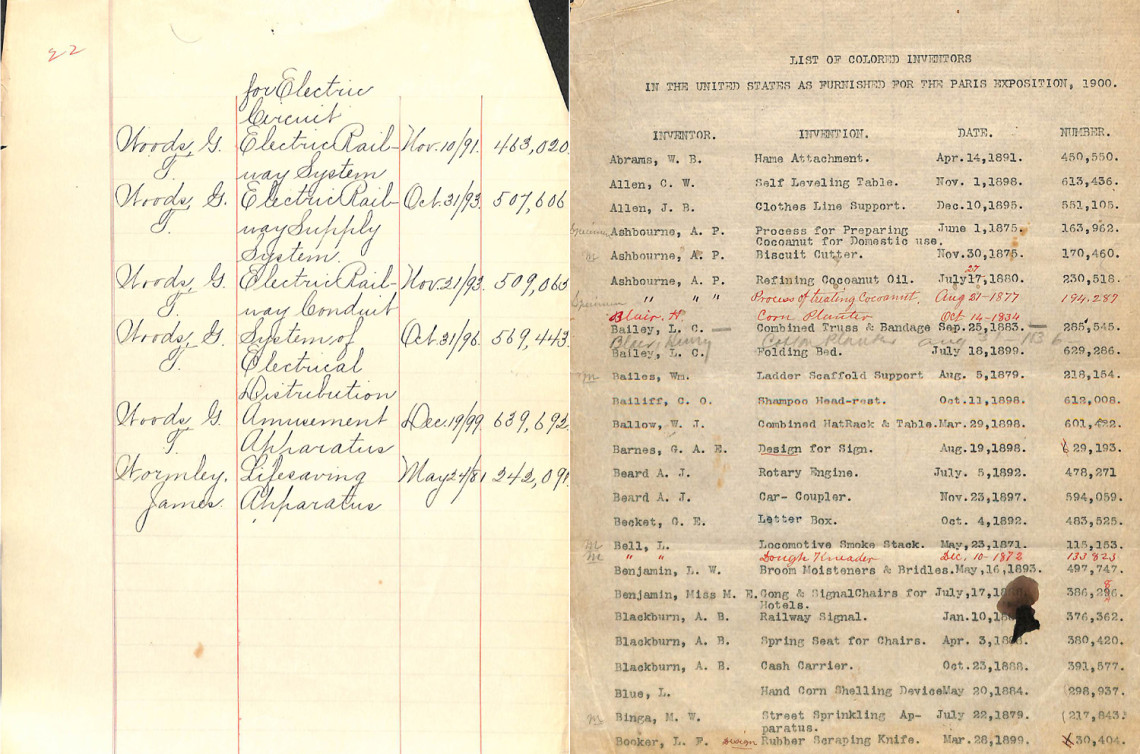

In the 1880s, second assistant patent examiner Henry E. Baker took on a project that would become his legacy: compiling the first list of African American patent holders. Over the next few decades, Baker’s list would grow to several hundred entries, an immense repository of contributions by Black inventors to the technological progress of humanity and a powerful record of the public quest for racial equality at the turn of the 20th century.

Thanks to Baker's tireless research, we have at our fingertips a vast repository of Black innovation throughout early U.S. history. Keep reading to learn how the inventors on Baker's List have been changing the world for generations as creators, disruptors, and trailblazers in their respective industries, and how Black excellence in invention continues today.

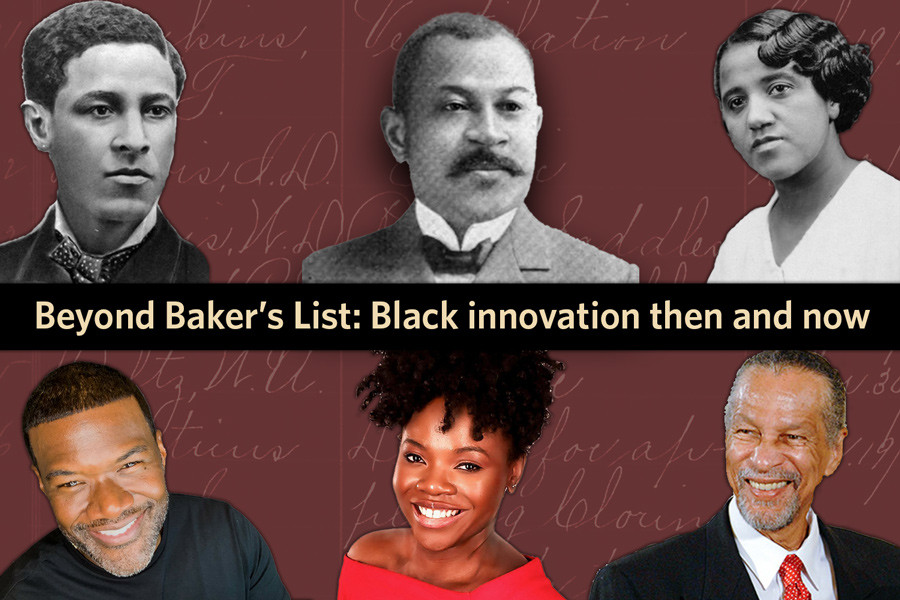

Left to right: Jan Matzeliger, Henry Baker, Marjorie Stewart Joyner (top), Cornell Conaway, Tope Mitchell, James West (bottom)

One of the inventors on Baker's List was Jan Matzeliger, who in 1883 changed the shoe industry forever with his automatic lasting machine. Born in Dutch Guiana (now Suriname), Matzeliger immigrated to the United States at the age of 20 and took a job operating a shoe-stitching machine. After watching the work of hand lasters at the factory, he set out to make the process of joining the sole to the upper part of the shoe more efficient. Matzeliger built his first model out of wooden cigar boxes, elastic, and wire, a prototype so complex that patent examiners had to see it in operation to understand how it worked. Matzeliger's invention could produce 700 pairs of shoes per day, up from 50, making quality shoes widely affordable for the first time.

About 15 years later, in 1898, Lyda D. Newman received a patent for a hairbrush with fine synthetic bristles and an inner chamber that trapped dust and dirt. Reflecting expertise collected from her career as a hairdresser in New York City, Newman's invention paved the way for other Black innovators to further revolutionize the hair-care industry, including 2023 National Inventors Hall of Fame inductee Marjorie Stewart Joyner.

Newman's innovative mind blazed a trail for others to follow in many important areas. In the 1910s, she led efforts by the Woman Suffrage Party (WSP) to involve Black women in the struggle for the vote. Having built a grassroots suffrage campaign in her Manhattan neighborhood of San Juan Hill, she was approached to lead the effort for women's suffrage among Black New Yorkers in 1915. The New York Times and other papers took notice of some of Newman's strategies, including providing a daycare at WSP headquarters in San Juan Hill so that mothers wouldn't have to choose between childcare and political involvement.

Lyda Newman's 1898 patent for a hairbrush. One of the few women inventors on Baker's list, Newman overcame the dual obstacles of racism and sexism in receiving a patent.

Studying Baker's list reveals inventor after inventor whose experiences helped them identify and solve problems, building upon existing products and innovations with their ideas. Alfred Cralle, a porter in a Pittsburgh hotel, invented the one-handed ice cream scoop still in use today. Sarah Boone, a dressmaker from New Haven, Connecticut, patented an improved ironing board shaped specifically for bodices and sleeves. If you use a lawn-mower attachment to collect grass clippings, you have Daniel Johnson of Kansas City, Missouri to thank. And, the eye protector patented by Powell Johnson of Barton, Alabama helped firefighters and furnace workers protect their eyesight from the bright glare of the fire.

The triumphs of these individuals reflect a time where, as the nation industrialized, more Americans were inventing than ever before. But Black innovators faced numerous challenges, including racist attitudes that prevented commercialization of their products. “We can never know the whole story,” Henry Baker lamented in his notes, as many inventors chose not to reveal their race, fearing it would harm the commercial value of their invention.

Progress was hard-fought and uneven. Nevertheless, the inventors on Baker's list laid the foundation for today's change-makers, some of whom joined us this month to tell their stories during our Black Innovation & Entrepreneurship programs:

- Dissatisfied with the workout grip devices available on the market, Cornell “Chico” Conaway started Gainz Sportsgear after designing and patenting Load N Lock Grips, which are longer and thicker than traditional grips.

- With over 250 patents, Jim West, a winner of the National Medal of Technology and Innovation, is best known for his invention of the electret microphone, technology that represents 90% of the microphones produced annually and found in everyday items like your cell phone.

- Tope Mitchell used her PhD in sociology to found Reflekt Me, a company that hyper-personalizes eCommerce sites to create inclusive communities, allowing fashion and beauty brands to engage with 100% of their digital buyers.

During our final Black Innovation & Entrepreneurship event of 2023 on February 24, we premiered the documentary short "America's Ingenuity," created in partnership with the National Inventors Hall of Fame (NIHF). The film focuses on Richard F. America, one of the youngest Black inventors on Baker's list, and features an interview with his son. We also announced the USPTO will rename its Public Search Facility after Henry Baker, honoring both his dedicated career as a civil servant and his contributions to the historical record.

In the film “America's Ingenuity,” Richard F. America Jr., shares memories of his father, including information about his inventions, activism, and career as a public servant.

As we learn more about the inventors on Baker's list, we will continue to share their unique stories. In the style of Henry Baker, we are also using crowdsourcing to learn as much as we can. Here's how you can help us document and recognize the history of Black innovation:

- If you are the descendant of a Black inventor, or know of a past innovator who lived or worked in your community, please reach out to historian@uspto.gov.

- Nominate a world-changing innovator to receive the National Medal of Technology and Innovation, the nation's highest honor for technological achievement.

- Consider nominating an inventor to be included in a future class of the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

We can never know the whole story, but by studying and expanding on Baker's work, we can get a much fuller picture of the Black creators, trailblazers, and disruptors who helped invent modern America. We are proud to honor these innovation heroes.

For more information about upcoming events for innovators, visit our Innovation events for all page.