A strong will

In 1883, Harriet Williams Russell Strong—a graduate of Miss Mary Atkin’s Young Ladies Seminary, mother of four, and recent widow—became the sole owner of a California ranch on the brink of financial ruin.

Her will to learn saved her ranch and led to several patents. Later, her advocacy to Congress would forever change how water is managed in the western United States.

6 min read

Each month, our Journeys of Innovation series tells the story of an inventor or entrepreneur whose groundbreaking innovation has made a positive difference in the world. Delve into the past to learn about one of history’s great innovators.

The terrible news traveled across the continent, reaching Harriet Strong in Philadelphia just as a new treatment for her lifelong spinal issues was showing promise: Her husband had once again lost money in a business venture, a “salted” mine this time. But this latest failure proved insurmountable for Charles Strong, and in its wake he’d taken his own life. Harriet wrote her four daughters, aged 10 to 14, at home in Whittier, California. They urged her to complete her course of medical treatment. After several more months, her health improved, Harriet steeled herself and returned to Whittier, determined to defend the family’s 220-acre Rancho del Fuerte—the ranch of the strong—from her deceased husband’s circling creditors.

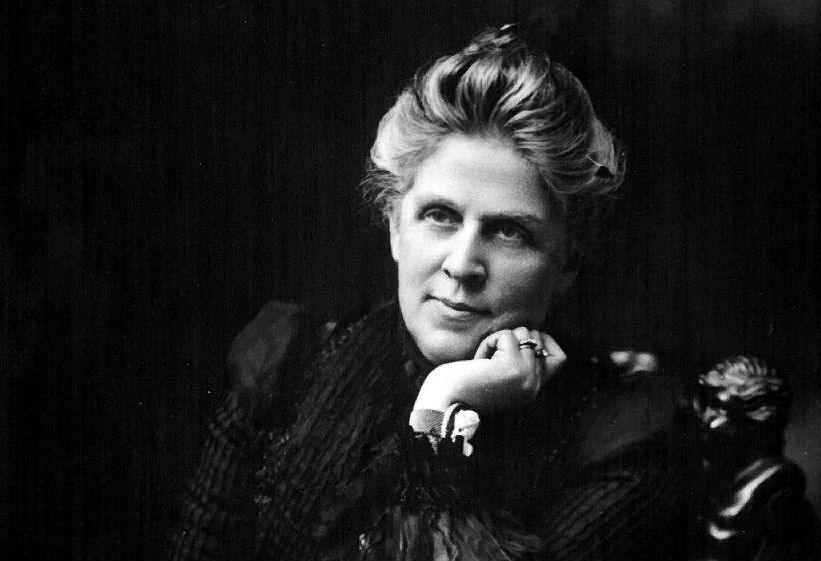

(Top image) Harriet Williams Russell Strong. (Bottom image) Harriet Strong surrounded by her daughters Mary, Georgina, Nelle, and Hattie (both circa 1900). Courtesy of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Though untrained for her new role and still requiring frequent bedrest, Harriet threw herself into learning all she could about the business of agriculture. She voraciously read through scientific books and journals while enlisting the help of other local ranchers who could answer her questions about water, soil, crops, and marketing. “I had the courage of ignorance and plenty of determination to back it up,” she would later say.

Walnuts, Harriet learned, were among the most profitable of crops, and so 150 acres were planted on the ranch. But walnuts also required copious amounts of water and time to mature, so she needed a plan to generate income in the interim; she found it in a plant native to South America. Between the rows of walnut trees, she seeded fast-growing Argentine pampas grass.

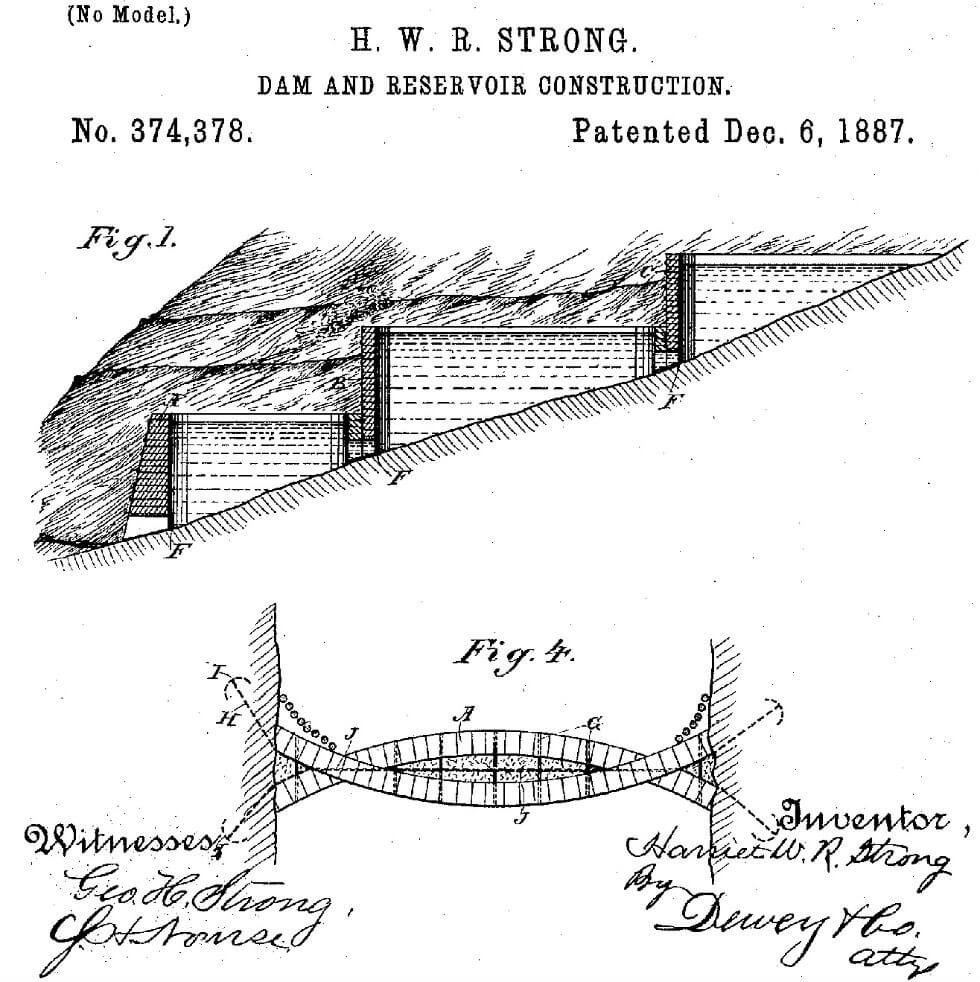

The new walnut trees were thirsty, and so sometimes—to borrow from a popular adage—invention is actually a mother’s necessity. To mitigate flash floods that regularly devastated the Los Angeles basin and capture the storm water for later agricultural use, Harriet designed elaborate irrigation and water control systems. She created a series of ascending dams that helped store water while also acting as a reinforcement for the dam above it. Starting in 1887, she patented several inventions for dam and reservoir construction and irrigation systems.

Harriet Strong’s patent for “Dam and Reservoir Construction,” issued in 1887. Strong ultimately became the named inventor on five U.S. patents.

Her irrigation and water conservation inventions allowed walnuts to flourish in the semi-arid Southern California soil, and within five years Harriet would have the largest walnut farm in the United States, earning her the nickname “Walnut Queen of Whittier.”

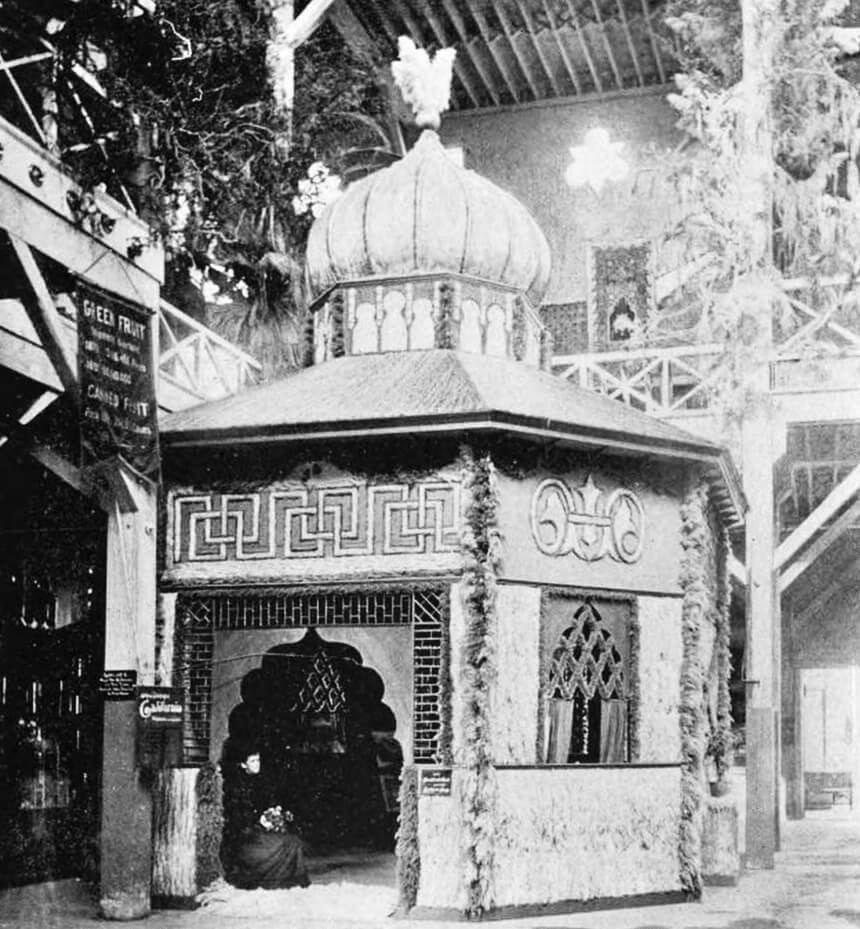

The final report of the World’s Fair described the lavish “novel decorations” of the palace, including an American flag and rugs made of the grass, noting that “the effect was rich in the extreme” (1894). Courtesy of the California State Office, accessed from Google Books.

Faddish and lucrative, pampas plumes sold wholesale for 4 cents (about a dollar today), and were used as an economical alternative to the bird feathers adorning the elaborate Victorian hats of the day. And when the fancy hat craze faded, she found new markets for her pampas grass by convincing the organizers of the 1892 and 1896 Democratic and Republican national conventions to purchase her plumes dyed in red, white, and blue, to wave proudly on the convention floors.

Harriet traveled to the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1893, where she won two medals for her inventions and drummed up publicity for her crops by designing and building, with her daughters’ help, the award-winning Pampas Plume Palace, made almost entirely of the grass.

Her now-profitable farm, which she had successfully defended from foreclosure, made Harriet a wealthy woman, but her drive for self-preservation had strengthened into a force for social change. During the fair, she spoke at a congress on business training for women, urging them to learn all they could. “When the majority of women understand the business methods of the world,” she said, “they will be asked to assist in the affairs of government.”

Harriet became an ardent supporter of women’s voting rights and was a member of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, speaking alongside Susan B. Anthony at events and even hosting her for a visit to Rancho del Fuerte in 1895.

Crops in the California Imperial Valley, circa 1919. This unique image medium, known as a “lantern slide,” was used in early 20th century visual instruction. Courtesy of Oregon State University Special Collections.

As she often told women’s business groups, Harriet’s participation in government came alongside her success in business. She was the force behind the Los Angeles Flood Control Act of 1915 and held public office on the flood control board before women even had the right to vote in California. In 1918, she became the first woman delegate at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce convention.

During World War I, Harriet advocated for a national irrigation system. She traveled to Washington, D.C., to present Congress with a plan to dam the Colorado River at the lower end of the Grand Canyon to help control floods, conserve water, generate electricity, and provide irrigation to farms that would enable America to send enough food abroad to support the Allied armies and the civilian victims of war. “The distressed world has become our world,” she wrote.

Congress rejected her plan as the war ended, but Harriet was convinced that it had merit and was only rejected because, as she said, “It was thought of by a woman.”

History would prove her right.

“…she had the brains to think up a way out and the courage and perseverance to carry her ideas to completion.”

Following Harriet’s tragic death in a car accident in 1926, some of her most transformative ideas became reality. The Hoover Dam was approved by Congress in 1928 and completed in 1935. That act also mandated the All-American Canal, based on Harriet’s ideas, which began construction in 1942 and is now the world’s largest irrigation canal, carrying water from the Colorado River into California’s Imperial Valley.

The Hoover Dam today. Courtesy of U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Photo by Alexander Stephens.

Today, California remains the United States’ leading agricultural producer, growing a third of the nation’s vegetables and two-thirds of its fruits and nuts. The Hoover Dam is still one of the country’s largest hydroelectric plants, generating electricity for 1.3 million people. Her foresight and entrepreneurship may have rescued her family from tragedy, but Harriet Strong changed the face—and sustenance—of our country for the better with her innovations in water movement and crop irrigation.

References

Alpern, Sara. "Harriet Williams Russell Strong: Inventor and California Businesswoman Extraordinaire." Southern California Quarterly 87, no. 3 (2005) 223-268.

Hattie Strong to Harriet Strong, February 9, 1883. Cited in Alpern, 233.

Marovich, Lisa A. “Let Her Have Brains Too.” Business and Economic History 27, no. 1 (1998): 150.

“Successful Women,” December 25, 1904. Box 18, folder of clippings, Strong Papers. Cited in Alpern, 235.

Rasmussen, Cecilia. “‘Walnut Queen’ Broke Lots of New Ground.” Los Angeles Times, February 28, 1999.

Strong, Harriet Williams Russell. “Can the United States Feed the World?” The New American Woman 2, no. 11 (1917): 3-4. Cited in Alpern, 256.