Of courage and caution

Two accidents brought inventor Garrett Morgan into the national spotlight, but it was his determination, resourcefulness, and dedication to public service that made him a success. By patenting and marketing his smoke hood and traffic signal, Morgan saved lives. Throughout his career, he found innovative ways to make his community a better place for all.

19 min read

Each month, our Journeys of Innovation series tells the stories of inventors or entrepreneurs who have made a positive difference in the world. This month, Rebekah Oakes' story focuses on Garrett Morgan, who was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for his safety-related patents for a smoke hood and traffic signal.

Do you know an innovator or entrepreneur with an interesting story?

In the early morning hours of July 25, 1916, Garrett Morgan awoke to the incessant ringing of the telephone. On the line was Cleveland’s police department. There had been a disaster at the new West Side waterworks, and they needed Morgan’s help.

Through frantic explanations, a picture of the situation began to emerge. An explosion left a work crew trapped underground, four miles out into Lake Erie, buried under hundreds of feet of mud and debris. Two previous rescue parties had succumbed to the dangerous natural gas filling the tunnel. Time was quickly running out.

Within the hour, Morgan and his brother Frank reached the entrance to the tunnel with around twenty of Morgan’s patented safety hoods. Confident in his product and driven to save lives, Morgan donned the fabric smoke hood and led the third rescue party down the tunnel. Thanks to his invention, Morgan and the other rescuers were able to find eight survivors in a disaster that took 20 lives.

Morgan was a hero, but the response to his daring rescue mission, both in town and across the country, was uneven.

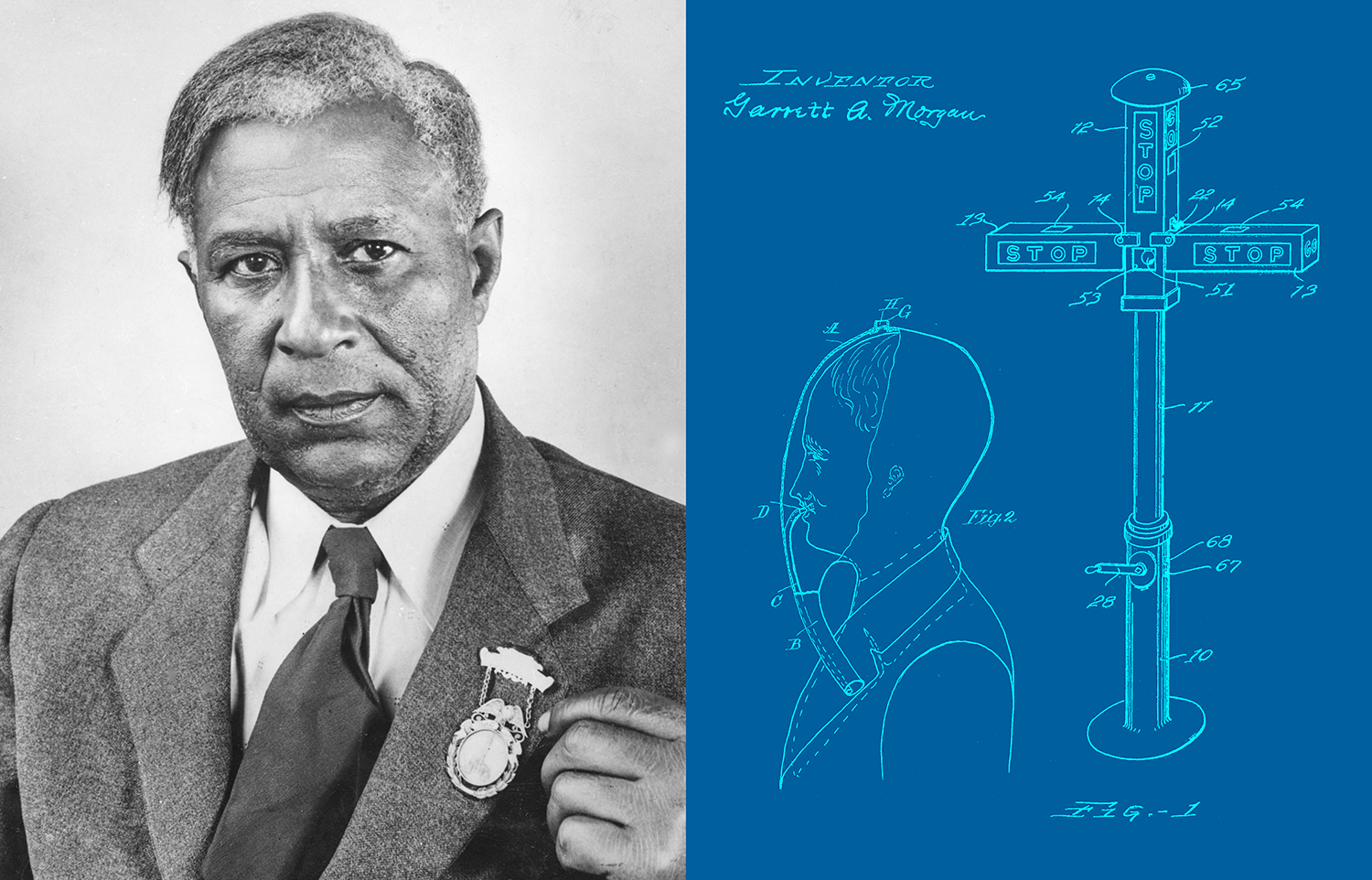

Garrett Morgan, undated.

(Courtesy of Western Reserve Historical Society)

He was awarded medals for bravery from a Cleveland civic association and the International Association of Fire Engineers but was denied the monetary compensation that other rescuers received. Four white men who participated in the tunnel rescue were awarded medals by the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission, but the city refused to support Morgan’s nomination for the same. A number of fire departments placed new orders for the safety hood, while some Southern cities canceled theirs after learning the inventor was Black- a fact that Morgan purposefully hid from the public prior to the disaster.

Today, Garrett Morgan is one of the most well-known African American inventors of the early 20th century, but during his era he faced pervasive and systemic racism both in his professional and personal life.

Born to Sidney and Eliza Morgan around 1877, Garrett Morgan grew up in the hamlet of Paris, Kentucky. One of several children in a rural community, Morgan’s early life did not afford many opportunities for formal education. With only six years of schooling, he moved across the Ohio River to Cincinnati at the age of 14. With a portion of his wages, he hired a tutor and continued his education.

The turn of the 20th century was a time of great change for Morgan. He moved to Cleveland, Ohio in 1895, taking a position sweeping floors at a dry goods factory for $5 per week. This job introduced him to an industrial environment vastly different from the agricultural community in which he’d grown up. Navigating all the challenges and opportunities that came with a major metropolitan city, Morgan made the transition from wage worker to entrepreneur and business owner within a decade.

Garrett Morgan’s Cleveland was a city on the rise. The city’s lifeblood was its location, nestled on the shores of Lake Erie. The ease of transporting goods propelled Cleveland to the status of a major manufacturing city following the Civil War. Readily available jobs in the city’s industrial sector attracted immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe, as well as African Americans from the rural South, transforming Cleveland into a cultural melting pot. The population increased exponentially, and the city invested in architecture, parks, and the arts.

This time period afforded more opportunities for Black entrepreneurs and business owners than ever before. Morgan moved to Cleveland on the early cusp of the Great Migration, a mass movement of African Americans from the rural South to cities in the North and West. Wage work in these cities opened up new consumer bases, and Black entrepreneurs eagerly marketed products to these emerging communities.

Cleveland doubled in population between 1900 and 1920, growing to the nation’s fifth-largest city.

(Courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library)

Morgan’s next career move was into Cleveland’s thriving garment industry. He took up a position with the H. Black Company, a major manufacturer of women’s suits and cloaks. Looking to increase efficiencies in his new trade, Morgan designed a belt fastener for sewing machines and sold it for $150.

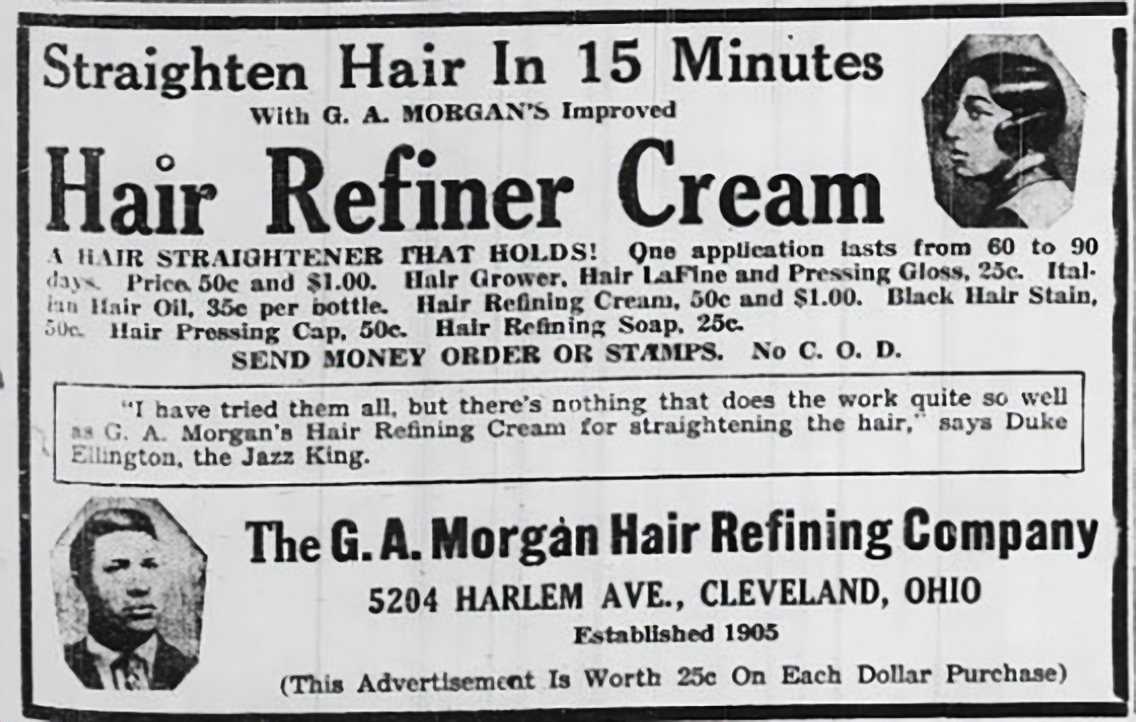

Morgan advertised his hair refiner cream extensively to Black customers in African American-run newspapers.

(Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

Sewing machine improvement also indirectly led to the product that would launch his longest-running business venture: the G.A. Morgan Hair Refining Company. While experimenting with a liquid that prevented a sewing needle from burning fabric, Morgan realized it could also straighten hair. Reformulating it into a hair-refining cream, he joined an already thriving market targeting African American consumers. Barbers and hairdressers represented nearly half of Black business owners and professionals in the first decade of the 20th century, and the need for products suitable for Black hair brought a lot of innovation (and money) into the field of cosmetics. Advertisements for his product proclaimed ease of use, affordability, and fast-acting results.

It was through the garment industry that Morgan met Mary Hasek. The Hasek family had immigrated to the United States from Bohemia (modern day Czech Republic) in 1893, becoming part of Cleveland’s growing and thriving immigrant community. The 1900 census listed Mary as a sewer in a tailor shop, an occupation commonly held by immigrant women at the time. Sometime prior to 1908, Garrett and Mary fell in love.

However, their relationship presented them with an immediate challenge: Garrett was Black, and Mary was white.

As an interracial couple at a time when segregation was becoming more common and white supremacist violence was on the rise, Garrett and Mary faced discrimination from their employers and even from family. According to their granddaughter, Sandra Morgan, Morgan’s employer gave him an ultimatum: end his relationship with Mary or be fired. He quit instead, and Mary soon followed suit. After they married, Mary’s father petitioned the Catholic bishop and had her excommunicated from the Catholic church, and her siblings had to visit her in secret to maintain a relationship.

The Morgans persevered and soon became partners in business as well as life. Following their forced exits from their jobs, Garrett and Mary put their skills in the textile industry and entrepreneurial spirit to use and opened Morgan’s Cut Rate Ladies Clothing Store. They eventually employed 32 workers. An article in the Kansas City Advocate described that Morgan “takes great pleasure in giving his wife a great deal of the credit for the [results] that he has attained.”

By 1910, Morgan owned a house at 5202 Harlem Avenue in Cleveland, an address that would appear on advertisements for his hair refining company for decades. By 1920, the family of two had expanded to five. Garrett and Mary raised their three sons, John, Garrett Jr., and Cosmo, in the Harlem Avenue home. Morgan lived there for the rest of his life.

Already the owner of two successful businesses, he turned his attention to another area of interest: public safety.

Morgan modeling his safety hood. He received two patents for his “breathing device” in 1914: U.S. Patent no. 1,090,936 and U.S. Patent no. 1,113,675.

(Courtesy of Cleveland Memory/Cleveland Press Collection/The Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University)

Having worked in Cleveland’s bustling factories, Morgan knew first-hand just how dangerous industrial buildings could be for workers and firefighters alike. Volatile chemicals resulted in frequent explosions. Tufts of cotton and other fibrous materials filled the floors of garment warehouses, kindling for potential fires. Cramped working conditions in multi-level buildings made emergency escape for factory workers difficult. In 1911, a tragedy in New York threw these hazards into sharp relief. A fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company killed 146 garment workers, mostly young immigrant women, like Mary Morgan had been just a few years prior.

Morgan identified one consistent issue with industrial fires. Due to heavy, often chemical-laden smoke, firefighters were not able to enter the buildings and rescue any survivors without becoming victims themselves. With his first patented invention, he sought to change that.

In 1914, Morgan was granted two patents for his “breathing device,” a smoke hood that was both practical and innovative. The invention consisted of a hood with a hanging air tube attached, relying on the idea that the most noxious of smoke and fumes would rise to the top of a space. The tube allowed a firefighter to breath the cleaner air from near the floor, or momentarily placed through an open window. A valve at the top of the hood “permits the foul air in the hood to escape as fresh air is driven into the hood.” The device allowed firefighters, or workers in other poorly ventilated spaces, to enter a smoke-filled space for a period of time without suffocating.

The smoke hood was a commercial success. A fire chief in Yonkers, New York was “so impressed with the Morgan Safety hood” that he ordered six for use in his fire department following a demonstration. Firefighters in Connecticut cited its light weight and simple construction as positives; the hood allowed them to move around easily, with their hands and feet unencumbered. Morgan was awarded first prize for safety hood at a 1914 exposition of safety and sanitation in New York City. A Kansas newspaper declared the Morgan National Safety Hood and Smoke Protector one of “the best types on the market.”

Like many inventors, Morgan took an active role in marketing his product. But unlike his white peers, he had to take racial prejudice into consideration when developing his commercial marketing strategy.

In the early 20th century, inventors commonly gave public demonstrations and personally appeared on advertisements for their products. Exhibitions and road shows were primary methods of bringing an invention to market, particularly for a product like Morgan’s, where efficacy could mean the difference between life and death. For Black inventors looking to sell to interracial audiences, however, these public demonstrations were a barrier to success. Not only were inventions often segregated at large exhibitions and trade shows based on the race or gender of the inventor, but some white consumers would outright refuse to purchase products if they knew the inventor was Black.

Morgan came up with a solution to sell his product. First, he listed prominent white businessmen in Cleveland as executives on the letterhead for his new company, the National Safety Device Company. For public appearances, he hired a white man to act as the primary salesman while he conducted the actual demonstration of its effectiveness. Morgan even adopted an alias: George Mason, a Native American assistant who would demonstrate the smoke hood. A Times-Picayune article from 1914 describes Morgan, identified as “Big Chief” Mason, testing the smoke hood in a fire fueled by a horrifically smelling mixture of tar, sulfur, formaldehyde, and manure.

Ads like this one, featuring a well-dressed white actor modeling Morgan’s product, were a common marketing strategy for African American inventors.

(Courtesy of Google Books)

“The smoke was thick enough to strangle an elephant,” the New Orleans newspaper reported, “but Mason lingered around in the suffocating atmosphere for a full twenty minutes and experienced no inconvenience.” Instead of the face of the invention, Morgan would be the one to prove its worth.

Morgan’s absence in advertisements for his safety hood stands in marked contrast with those for his hair refiner cream. Newspaper and magazine advertisements for his earliest business venture span decades. Consistently listing Morgan’s name and home address, the ads feature African American faces, including Morgan himself. One ad from 1933 even features a quote from Jazz musician Duke Ellington, proclaiming, “I have tried them all, but there’s nothing that does the work quite so well as G.A. Morgan’s Hair Refining Cream for straightening hair.”

What explains the difference between these distinct marketing strategies? In a word, the audience. Morgan was trying to sell his hair refiner cream directly to Black consumers, whereas prospective buyers for his safety hood were primarily white fire chiefs and government officials.

At the root of Morgan’s motivations for inventing was a desire to solve problems and help people. To do that he made the difficult, intentional choice to separate invention from inventor.

“He couldn’t help himself when he saw a problem. He had a humanitarian spirit that needed to help."

His determination to save lives meant he would not remain anonymous forever.

The incident that led the Cleveland police department to call on Garrett Morgan in July of 1916 was the consequence of rapid population growth and a city struggling to keep up. In addition to its importance to transportation, Lake Erie had been the source of fresh water for Cleveland’s citizens since 1856. As the population expanded, so did pollution in the lake, and the city constructed its first waterworks tunnel in 1874. These tunnels were designed to extend from the shore to water intake “cribs,” sometimes miles out into the lake, where the water was untainted by pollution. A second tunnel, then a third, proved inadequate as Cleveland’s population grew by hundreds of thousands every decade. In 1910, with typhoid fever on the rise, a fourth tunnel was authorized, one that would eventually extend four miles out into the lake.

This photo of Morgan at the tunnel disaster appeared in the Cleveland Gazette, one of the few publications to give Morgan credit for the rescue.

(Courtesy of Cleveland Memory/Cleveland Press Collection/The Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University)

Work began in 1914. This was difficult and dangerous work for the laborers; 33 workers had died during the construction of the previous tunnel. At first, safety had seemingly improved on the new project, but that all changed on July 25, 1916. Natural gas vented up from the lakebed and somehow caught fire, trapping a work crew under hundreds of feet of detritus, miles from shore. Using his safety hood, Morgan and members of the third rescue party were able to successfully retrieve eight trapped workers. Although Garrett Morgan took care to conceal his identity from consumers nationally, Clevelanders had long known who was the true inventor of Morgan’s National Safety Hood. His daring rescue would shed light on the racial hypocrisy of the times.

According to one article in The Monitor, an African American run newspaper, Cleveland mayor Henry Davis was the “the last man to shake Morgan’s hand before he went down… and the first man to congratulate him when he returned.” The mayor was highly aware of Morgan’s role in the rescue, yet his reluctance to publicly honor him led Morgan to write him a letter containing the forthright statement, “I am not a well-educated man; however, I have a Ph.D. from the school of hard knocks and cruel treatment.”

Morgan was a hero. But he was still a Black man facing pervasive and systemic racism.

"I have a Ph.D. from the school of hard knocks and cruel treatment."

Unlike the largest news organs of the time, Garrett Morgan’s career was well-documented in African American-run newspapers across the country long before the tunnel disaster. The New York Age covered a 1915 meeting between Morgan and bankers from J.P. Morgan, Co. regarding a potential recommendation of the safety hood for use by the British Army, already embroiled in the conflict of the First World War. In a glowing article entitled “A Man of worth To the Race,” the Kansas City Advocate commended Morgan’s “wonderful inventive brain together with remarkable business ability.” The 1916 piece goes on to declare, “All the more credit is due to him when we consider the fact that he has accomplished so much without the learning of books, but with the teaching as he has well chosen to put it himself, to the college of hard knocks.” The Monitor centered on Morgan in their reporting of the tunnel disaster, while many other newspapers failed to mention him at all.

Morgan had long been involved in organizing for the Black community in Cleveland as a co-founder of the Cleveland Association of Colored Men nearly a decade before the tunnel disaster. But perhaps this dichotomy in press coverage spurred one of Morgan’s next civic-minded projects. In 1920, he founded a weekly newspaper, the Cleveland Call.

The unfair treatment following the tunnel disaster left bitterness, but Morgan continued his work. In 1918, with the United States entering the war in Europe, the Denver Star reported that Morgan received an order for safety hoods from the U.S. Navy. They were to be used to equip warships still under construction, and the newspaper declared it a “racial success.”

While continuing to grow his existing businesses, Morgan soon turned his inventive mind to a different challenge: the public safety issues stemming from traffic.

Inexperienced drivers and varied forms of transport created traffic nightmares in the early decades of the 20th century.

(Courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library)

In the early 1920s, automobile travel was still a luxury, which meant that vehicles shared the roads with pedestrians, horse-drawn carriages, bicycles, and even streetcars. Traffic laws and infrastructure were slow to catch up with this emerging technology, and busy city intersections became increasingly hazardous. The fact that most drivers were new and inexperienced added fuel to the (quite literal) potential for fire. This was such a concern that newspapers routinely printed practical driving advice such as “the good driver watches the road far in advance of his car,” and “obey to the letter all traffic signs and signals.” Unfortunately, one of the issues was a lack of standardized signals altogether.

Sometime in the early 1920s, Morgan was driving with two of his young sons in the car. The Morgans witnessed a collision between an automobile and a horse-drawn cart at an intersection, resulting in a young girl being ejected from the carriage and an injured horse needing to be humanely euthanized in the street. Ever the problem-solver, Morgan turned his attention to preventing incidents like this from happening.

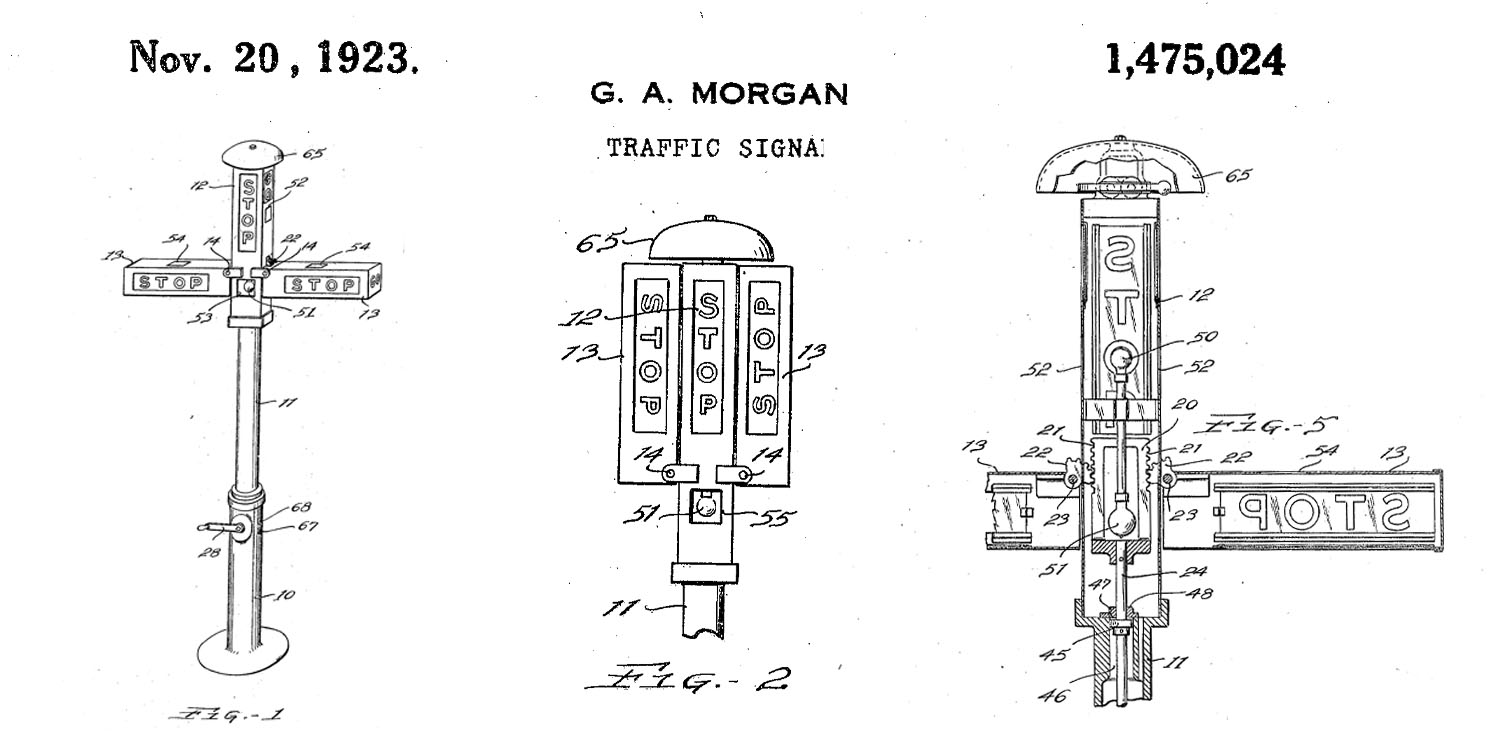

On November 20, 1923, he was granted a patent for his improved traffic signal. Made up of movable arms that could be adjusted with a hand-crank, the signal could be maneuvered into different positions to indicate if traffic (vehicular and pedestrian) should “stop” or “go” from a given direction. It also contained a step in-between, which would stop traffic in all directions, clearing an intersection. He wrote in his patent that this option would help in “avoiding accidents which frequently occur by reason of the over-anxiety of the waiting drivers to start as the signal to proceed is a given.” This caution signal was a significant improvement over previous traffic signal designs.

Morgan intended for his traffic signal to be more visible than the police officer typically present at busy intersections.

(Courtesy of Western Reserve Historical Society)

Just like with his safety hood, Morgan recognized the need for a public demonstration to tempt prospective customers. He chose to install his first traffic signal in Willoughby, Ohio, a more rural community than Cleveland that still had a large enough intersection to demonstrate the invention’s necessity. After this public demonstration, representatives from General Electric became interested in the technology and purchased the rights to his patent for $40,000.

In practice, Morgan’s traffic signal was complex and did not see widespread use, especially as electric traffic signals soon replaced mechanical ones. But today, we are very familiar with the most significant part of Morgan’s invention; we call it the caution, or “yellow” light.

The contract with General Electric was life-changing, even for an already successful entrepreneur like Morgan.

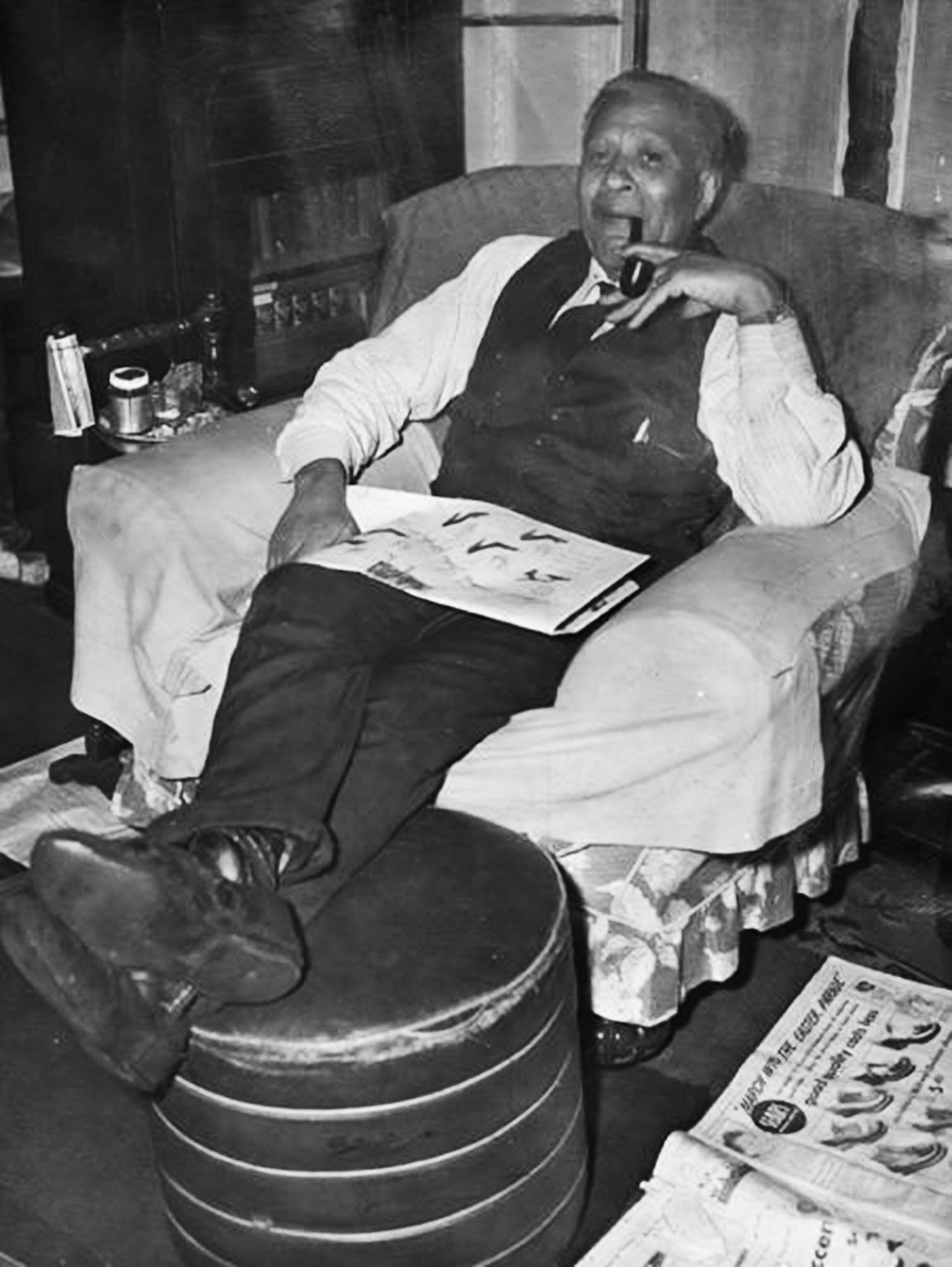

Garrett Morgan, 1948.

(Courtesy of Cleveland Memory/Cleveland Press Collection/The Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University)

“He was able to relax a little bit,” Sandra Morgan explained. “He was able to pursue other activities that were more civic-oriented.”

Relaxation, in this case, meant ensuring others had the opportunity to relax as well. He bought 250 acres of land and founded the Wakeman Country Club, where African Americans could get away from the city and enjoy recreational activities. Cities in the early 20th century were places of opportunity, but they could also be loud, smelly, and dusty. Since Black citizens were often barred from established country retreats, Morgan created a place that all could enjoy. The country club featured activities like dancing and horseback riding, attracting patrons as far away as Pittsburgh.

In his later years, Morgan continued to innovate and serve his community. He invented a self-extinguishing cigarette to prevent fires caused by people smoking in bed. In a campaign for city council in 1931 that he ultimately lost, he used the photo of the tunnel rescue on fliers denoting his scientific prowess and success as an inventor. He reinvested in his hair care line, and in 1956, he received his final patent for a de-curling comb that he claimed was economical to manufacture and easy to use.

Morgan’s dedication to his community, and family, was unquestioned. He invested in his children’s education, affording them opportunities unavailable to him in his youth. And Garrett and Mary hosted dinner for their family in their Cleveland home every Sunday evening. Attendance was mandatory, no excuses.

When asked about her grandfather’s legacy, Sandra Morgan answered with a laugh, “There was no slack in this man's army… everyone understood the mission. You are educated, you go to school, you are involved civically, you exhibit leadership as much as you can.”

After a protracted illness, Morgan died at the Cleveland Clinic on July 27, 1963.

A half-century after the Waterworks Tunnel Disaster, a young Sandra Morgan brought her grandfather’s safety hood into her kindergarten class for show and tell, teaching a new generation of Clevelanders about this exceptional inventor.

“I understood that he was a very special person and had brought something special to the world."

Credits

Produced by the USPTO’s Office of the Chief Communications Officer. For feedback or questions, please contact inventorstories@uspto.gov.

Story by Rebekah Oakes. Contributions by Whitney Pandil-Eaton and Eric Atkisson. Special thanks to Sandra Morgan, Western Reserve Historical Society, the Cleveland Public Library, Cleveland State University, and the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Image of Morgan with his medal for bravery at the beginning of the story is courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library.

References

Alabama Tribune (Montgomery, Alabama): “Garrett Morgan, Hero and Traffic Light Inventer [sic], Dies” (August 8, 1963).

Atlantic City Press (Atlantic City, New Jersey): “Garrett A. Morgan, Inventor of Gas Mask” (July 30, 1963).

Cook, Lisa D. “Overcoming Discrimination by Consumers during the Age of Segregation: The Example of Garrett Morgan,” Business History Review (Summer 2012): 211-234.

The Dallas Express (Dallas, Texas): “Cleveland Call Suspends Publication” (December 20, 1922).

The Denver Star (Denver, Colorado): “Interesting News Concerning the Race” (March 9, 1918).

DeLuca, Leo, “Black Inventor Garrett Morgan Saved Countless Lives with Gas Mask and Improved Traffic Lights,” Scientific American (February 25, 2021).

DePalma, Ralph, The Newark Leader (Newark, New Jersey): “The Art of Driving” (April 9, 1926).

Dubelko, Jim, “The 1916 Waterworks Tunnel Disaster,” Cleveland Historical, accessed September 12, 2023, https://clevelandhistorical.org/items/show/736.

Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut): “Demonstration of Fire Helmet” (September 24, 1914).

Hintz, Eric S. American Independent Inventors in an Era of Corporate R&D. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2021.

The Herald Statesman (Yonkers, New York): “New Style Helmets for Local Fire Fighters” (September 12, 1914.

Kansas City Advocate (Kansas City, Kansas): “A Man of worth To the Race” (April 21, 1916).

The McPherson Daily Republican (McPherson, Kansas): “Get Smoke Helmets” (January 7, 1918).

The Monitor (Omaha, Nebraska): “Colored Hero At Cleveland Disaster” (August 5, 1916).

The New York Age (New York, New York): “Inventor of Smoke Helmet in New York” (May 6, 1915).

The Pittsburgh Courier (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania): “Inventor of Traffic Light Dies” (August 17, 1963).

Sandra Morgan (granddaughter of Garrett Morgan), interview by Rebekah Oakes, October 6, 2023.

Sluby, Patricia Carter. The Inventive Spirit of African Americans. Westport: Praegar, 2004.

The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana): “Day Given Over to Sight-Seeing by the Firemen” (October 22, 1914).

U.S. Census records for Paris, Bourbon County, Kentucky (1880) and Cleveland, Cuyahoga County, Ohio (1900, 1910, 1920, 1930).

Washington, Roxanne, The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio): “Descendants of Cleveland’s 1916 Waterworks Tunnel disaster meet for the first time” (July 25, 1916).

The Weekly Echo (Meridian, Mississippi): “Cleveland Ohio News: A Surprise birthday party” (February 24, 1933).

The Yonkers Statesman (Yonkers, New York): “Test of Two Smoke Helmets” (September 12, 1914).