2111 Claim Interpretation; Broadest Reasonable Interpretation [R-10.2019]

CLAIMS MUST BE GIVEN THEIR BROADEST REASONABLE INTERPRETATION IN LIGHT OF THE SPECIFICATIONDuring patent examination, the pending claims must be “given their broadest reasonable interpretation consistent with the specification.” The Federal Circuit’s en banc decision in Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1316, 75 USPQ2d 1321, 1329 (Fed. Cir. 2005) expressly recognized that the USPTO employs the “broadest reasonable interpretation” standard:

The Patent and Trademark Office (“PTO”) determines the scope of claims in patent applications not solely on the basis of the claim language, but upon giving claims their broadest reasonable construction “in light of the specification as it would be interpreted by one of ordinary skill in the art.” In re Am. Acad. of Sci. Tech. Ctr., 367 F.3d 1359, 1364[, 70 USPQ2d 1827, 1830] (Fed. Cir. 2004). Indeed, the rules of the PTO require that application claims must “conform to the invention as set forth in the remainder of the specification and the terms and phrases used in the claims must find clear support or antecedent basis in the description so that the meaning of the terms in the claims may be ascertainable by reference to the description.” 37 CFR 1.75(d)(1).

See also In re Suitco Surface, Inc., 603 F.3d 1255, 1259, 94 USPQ2d 1640, 1643 (Fed. Cir. 2010); In re Hyatt, 211 F.3d 1367, 1372, 54 USPQ2d 1664, 1667 (Fed. Cir. 2000).

Patented claims are not given the broadest reasonable interpretation during court proceedings involving infringement and validity, and can be interpreted based on a fully developed prosecution record. In contrast, an examiner must construe claim terms in the broadest reasonable manner during prosecution as is reasonably allowed in an effort to establish a clear record of what applicant intends to claim. Thus, the Office does not interpret claims when examining patent applications in the same manner as the courts. In re Morris, 127 F.3d 1048, 1054, 44 USPQ2d 1023, 1028 (Fed. Cir. 1997); In re Zletz, 893 F.2d 319, 321-22, 13 USPQ2d 1320, 1321-22 (Fed. Cir. 1989).

Because applicant has the opportunity to amend the claims during prosecution, giving a claim its broadest reasonable interpretation will reduce the possibility that the claim, once issued, will be interpreted more broadly than is justified. In re Yamamoto, 740 F.2d 1569, 1571 (Fed. Cir. 1984); In re Zletz, 893 F.2d 319, 321, 13 USPQ2d 1320, 1322 (Fed. Cir. 1989) (“During patent examination the pending claims must be interpreted as broadly as their terms reasonably allow.”); In re Prater, 415 F.2d 1393, 1404-05, 162 USPQ 541, 550-51 (CCPA 1969) (Claim 9 was directed to a process of analyzing data generated by mass spectrographic analysis of a gas. The process comprised selecting the data to be analyzed by subjecting the data to a mathematical manipulation. The examiner made rejections under 35 U.S.C. 101 and 35 U.S.C. 102. In the 35 U.S.C. 102 rejection, the examiner explained that the claim was anticipated by a mental process augmented by pencil and paper markings. The court agreed that the claim was not limited to using a machine to carry out the process since the claim did not explicitly set forth the machine. The court explained that “reading a claim in light of the specification, to thereby interpret limitations explicitly recited in the claim, is a quite different thing from ‘reading limitations of the specification into a claim,’ to thereby narrow the scope of the claim by implicitly adding disclosed limitations which have no express basis in the claim.” The court found that applicant was advocating the latter, i.e., the impermissible importation of subject matter from the specification into the claim.). See also In re Morris, 127 F.3d 1048, 1054-55, 44 USPQ2d 1023, 1027-28 (Fed. Cir. 1997) (The court held that the USPTO is not required, in the course of prosecution, to interpret claims in applications in the same manner as a court would interpret claims in an infringement suit. Rather, the “PTO applies to verbiage of the proposed claims the broadest reasonable meaning of the words in their ordinary usage as they would be understood by one of ordinary skill in the art, taking into account whatever enlightenment by way of definitions or otherwise that may be afforded by the written description contained in applicant’s specification.”).

The broadest reasonable interpretation does not mean the broadest possible interpretation. Rather, the meaning given to a claim term must be consistent with the ordinary and customary meaning of the term (unless the term has been given a special definition in the specification), and must be consistent with the use of the claim term in the specification and drawings. Further, the broadest reasonable interpretation of the claims must be consistent with the interpretation that those skilled in the art would reach. In re Cortright, 165 F.3d 1353, 1359, 49 USPQ2d 1464, 1468 (Fed. Cir. 1999) (The Board’s construction of the claim limitation “restore hair growth” as requiring the hair to be returned to its original state was held to be an incorrect interpretation of the limitation. The court held that, consistent with applicant’s disclosure and the disclosure of three patents from analogous arts using the same phrase to require only some increase in hair growth, one of ordinary skill would construe “restore hair growth” to mean that the claimed method increases the amount of hair grown on the scalp, but does not necessarily produce a full head of hair.). Thus the focus of the inquiry regarding the meaning of a claim should be what would be reasonable from the perspective of one of ordinary skill in the art. In re Suitco Surface, Inc., 603 F.3d 1255, 1260, 94 USPQ2d 1640, 1644 (Fed. Cir. 2010); In re Buszard, 504 F.3d 1364, 84 USPQ2d 1749 (Fed. Cir. 2007). In Buszard, the claim was directed to a flame retardant composition comprising a flexible polyurethane foam reaction mixture. 504 F.3d at 1365, 84 USPQ2d at 1750. The Federal Circuit found that the Board’s interpretation that equated a “flexible” foam with a crushed “rigid” foam was not reasonable. Id. at 1367, 84 USPQ2d at 1751. Persuasive argument was presented that persons experienced in the field of polyurethane foams know that a flexible mixture is different than a rigid foam mixture. Id. at 1366, 84 USPQ2d at 1751.

See MPEP § 2173.02 for further discussion of claim interpretation in the context of analyzing claims for compliance with 35 U.S.C. 112(b) or pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 112, second paragraph.

2111.01 Plain Meaning [R-07.2022]

[Editor Note: This MPEP section is applicable to all applications. For applications subject to the first inventor to file (FITF) provisions of the AIA, the relevant time is "before the effective filing date of the claimed invention". For applications subject to pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102, the relevant time is "at the time of the invention". Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1313, 75 USPQ2d 1321, 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2005). See also MPEP § 2150 et seq. Many of the court decisions discussed in this section involved applications or patents subject to pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102. These court decisions may be applicable to applications and patents subject to AIA 35 U.S.C. 102 but the relevant time is before the effective filing date of the claimed invention and not at the time of the invention.]

I. THE WORDS OF A CLAIM MUST BE GIVEN THEIR “PLAIN MEANING” UNLESS SUCH MEANING IS INCONSISTENT WITH THE SPECIFICATIONUnder a broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI), words of the claim must be given their plain meaning, unless such meaning is inconsistent with the specification. The plain meaning of a term means the ordinary and customary meaning given to the term by those of ordinary skill in the art at the relevant time. The ordinary and customary meaning of a term may be evidenced by a variety of sources, including the words of the claims themselves, the specification, drawings, and prior art. However, the best source for determining the meaning of a claim term is the specification - the greatest clarity is obtained when the specification serves as a glossary for the claim terms. The words of the claim must be given their plain meaning unless the plain meaning is inconsistent with the specification. In re Zletz, 893 F.2d 319, 321, 13 USPQ2d 1320, 1322 (Fed. Cir. 1989) (discussed below); Chef America, Inc. v. Lamb-Weston, Inc., 358 F.3d 1371, 1372, 69 USPQ2d 1857 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (Ordinary, simple English words whose meaning is clear and unquestionable, absent any indication that their use in a particular context changes their meaning, are construed to mean exactly what they say. Thus, “heating the resulting batter-coated dough to a temperature in the range of about 400oF to 850oF” required heating the dough, rather than the air inside an oven, to the specified temperature.).

The presumption that a term is given its ordinary and customary meaning may be rebutted by the applicant by clearly setting forth a different definition of the term in the specification. In re Morris, 127 F.3d 1048, 1054, 44 USPQ2d 1023, 1028 (Fed. Cir. 1997) (the USPTO looks to the ordinary use of the claim terms taking into account definitions or other “enlightenment” contained in the written description); But c.f. In re Am. Acad. of Sci. Tech. Ctr., 367 F.3d 1359, 1369, 70 USPQ2d 1827, 1834 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (“We have cautioned against reading limitations into a claim from the preferred embodiment described in the specification, even if it is the only embodiment described, absent clear disclaimer in the specification.”). When the specification sets a clear path to the claim language, the scope of the claims is more easily determined and the public notice function of the claims is best served.

II. IT IS IMPROPER TO IMPORT CLAIM LIMITATIONS FROM THE SPECIFICATION“Though understanding the claim language may be aided by explanations contained in the written description, it is important not to import into a claim limitations that are not part of the claim. For example, a particular embodiment appearing in the written description may not be read into a claim when the claim language is broader than the embodiment.” Superguide Corp. v. DirecTV Enterprises, Inc., 358 F.3d 870, 875, 69 USPQ2d 1865, 1868 (Fed. Cir. 2004). See also Liebel-Flarsheim Co. v. Medrad Inc., 358 F.3d 898, 906, 69 USPQ2d 1801, 1807 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (discussing recent cases wherein the court expressly rejected the contention that if a patent describes only a single embodiment, the claims of the patent must be construed as being limited to that embodiment); E-Pass Techs., Inc. v. 3Com Corp., 343 F.3d 1364, 1369, 67 USPQ2d 1947, 1950 (Fed. Cir. 2003) (“Interpretation of descriptive statements in a patent’s written description is a difficult task, as an inherent tension exists as to whether a statement is a clear lexicographic definition or a description of a preferred embodiment. The problem is to interpret claims ‘in view of the specification’ without unnecessarily importing limitations from the specification into the claims.”); Altiris Inc. v. Symantec Corp., 318 F.3d 1363, 1371, 65 USPQ2d 1865, 1869-70 (Fed. Cir. 2003) (Although the specification discussed only a single embodiment, the court held that it was improper to read a specific order of steps into method claims where, as a matter of logic or grammar, the language of the method claims did not impose a specific order on the performance of the method steps, and the specification did not directly or implicitly require a particular order). See also subsection IV, below. When an element is claimed using language falling under the scope of 35 U.S.C. 112(f) or pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 112, 6th paragraph (often broadly referred to as means- (or step-) plus- function language), the specification must be consulted to determine the structure, material, or acts corresponding to the function recited in the claim, and the claimed element is construed as limited to the corresponding structure, material, or acts described in the specification and equivalents thereof. In re Donaldson, 16 F.3d 1189, 29 USPQ2d 1845 (Fed. Cir. 1994) (see MPEP § 2181- MPEP § 2186).

In Zletz,supra, the examiner and the Board had interpreted claims reading “normally solid polypropylene” and “normally solid polypropylene having a crystalline polypropylene content” as being limited to “normally solid linear high homopolymers of propylene which have a crystalline polypropylene content.” The court ruled that limitations, not present in the claims, were improperly imported from the specification. See also In re Marosi, 710 F.2d 799, 802, 218 USPQ 289, 292 (Fed. Cir. 1983) (“'[C]laims are not to be read in a vacuum, and limitations therein are to be interpreted in light of the specification in giving them their ‘broadest reasonable interpretation.'” (quoting In re Okuzawa, 537 F.2d 545, 548, 190 USPQ 464, 466 (CCPA 1976)). The court looked to the specification to construe “essentially free of alkali metal” as including unavoidable levels of impurities but no more.).

III. “PLAIN MEANING” REFERS TO THE ORDINARY AND CUSTOMARY MEANING GIVEN TO THE TERM BY THOSE OF ORDINARY SKILL IN THE ART“[T]he ordinary and customary meaning of a claim term is the meaning that the term would have to a person of ordinary skill in the art in question at the time of the invention, i.e., as of the effective filing date of the patent application.” Phillips v. AWH Corp.,415 F.3d 1303, 1313, 75 USPQ2d 1321, 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc); Sunrace Roots Enter. Co. v. SRAM Corp., 336 F.3d 1298, 1302, 67 USPQ2d 1438, 1441 (Fed. Cir. 2003); Brookhill-Wilk 1, LLC v. Intuitive Surgical, Inc., 334 F.3d 1294, 1298 67 USPQ2d 1132, 1136 (Fed. Cir. 2003) (“In the absence of an express intent to impart a novel meaning to the claim terms, the words are presumed to take on the ordinary and customary meanings attributed to them by those of ordinary skill in the art.”).

The ordinary and customary meaning of a term may be evidenced by a variety of sources, including the words of the claims themselves, the specification, drawings, and prior art. However, the best source for determining the meaning of a claim term is the specification – the greatest clarity is obtained when the specification serves as a glossary for the claim terms. See, e.g., In re Abbott Diabetes Care Inc., 696 F.3d 1142, 1149-50, 104 USPQ2d 1337, 1342-43 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (construing the term “electrochemical sensor” as “devoid of external connection cables or wires to connect to a sensor control unit” to be consistent with “the language of the claims and the specification”); In re Suitco Surface, Inc., 603 F.3d 1255, 1260-61, 94 USPQ2d 1640, 1644 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (construing the term “material for finishing the top surface of the floor” to mean “a clear, uniform layer on the top surface of a floor that is the final treatment or coating of a surface” to be consistent with “the express language of the claim and the specification”); Vitronics Corp. v. Conceptronic Inc., 90 F.3d 1576, 1583, 39 USPQ2d 1573, 1577 (Fed. Cir. 1996) (construing the term “solder reflow temperature” to mean “peak reflow temperature” of solder rather than the “liquidus temperature” of solder in order to remain consistent with the specification).

It is also appropriate to look to how the claim term is used in the prior art, which includes prior art patents, published applications, trade publications, and dictionaries. Any meaning of a claim term taken from the prior art must be consistent with the use of the claim term in the specification and drawings. Moreover , when the specification is clear about the scope and content of a claim term, there is no need to turn to extrinsic evidence for claim interpretation. 3M Innovative Props. Co. v. Tredegar Corp., 725 F.3d 1315, 1326-28, 107 USPQ2d 1717, 1726-27 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (holding that “continuous microtextured skin layer over substantially the entire laminate” was clearly defined in the written description, and therefore, there was no need to turn to extrinsic evidence to construe the claim). See also Seabed Geosolutions (US) Inc. v. Magseis FF LLC, 8 F.4th 1285, 1290, 2021 USPQ2d 848 (Fed. Cir. 2021) (finding that where the intrinsic evidence (i.e., the claims, written description and prosecution history) clearly supports a claim interpretation, it is unnecessary to resort to extrinsic evidence.).

IV. APPLICANT MAY BE OWN LEXICOGRAPHER AND/OR MAY DISAVOW CLAIM SCOPEThe only exceptions to giving the words in a claim their ordinary and customary meaning in the art are (1) when the applicant acts as their own lexicographer; and (2) when the applicant disavows or disclaims the full scope of a claim term in the specification. To act as their own lexicographer, the applicant must clearly set forth a special definition of a claim term in the specification that differs from the plain and ordinary meaning it would otherwise possess. The specification may also include an intentional disclaimer, or disavowal, of claim scope. In both of these cases, “the inventor’s intention, as expressed in the specification, is regarded as dispositive.” Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1316 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc). See also Starhome GmbH v. AT&T Mobility LLC, 743 F.3d 849, 857, 109 USPQ2d 1885, 1890-91 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (holding that the term “gateway” should be given its ordinary and customary meaning of “a connection between different networks” because nothing in the specification indicated a clear intent to depart from that ordinary meaning); Thorner v. Sony Computer Entm’t Am. LLC, 669 F.3d 1362, 1367-68, 101 USPQ2d 1457, 1460 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (The asserted claims of the patent were directed to a tactile feedback system for video game controllers comprising a flexible pad with a plurality of actuators “attached to said pad.” The court held that the claims were not limited to actuators attached to the external surface of the pad, even though the specification used the word “attached” when describing embodiments affixed to the external surface of the pad but the word “embedded” when describing embodiments affixed to the internal surface of the pad. The court explained that the plain and ordinary meaning of “attached” includes both external and internal attachments. Further, there is no clear and explicit statement in the specification to redefine “attached” or disavow the full scope of the term.).

A.LexicographyAn applicant is entitled to be their own lexicographer and may rebut the presumption that claim terms are to be given their ordinary and customary meaning by clearly setting forth a definition of the term that is different from its ordinary and customary meaning(s) in the specification at the relevant time. See In re Paulsen, 30 F.3d 1475, 1480, 31 USPQ2d 1671, 1674 (Fed. Cir. 1994) (holding that an inventor may define specific terms used to describe invention, but must do so “with reasonable clarity, deliberateness, and precision” and, if done, must “‘set out his uncommon definition in some manner within the patent disclosure’ so as to give one of ordinary skill in the art notice of the change” in meaning) (quoting Intellicall, Inc. v. Phonometrics, Inc., 952 F.2d 1384, 1387-88, 21 USPQ2d 1383, 1386 (Fed. Cir. 1992)).

Where an explicit definition is provided by the applicant for a term, that definition will control interpretation of the term as it is used in the claim. Toro Co. v. White Consolidated Industries Inc., 199 F.3d 1295, 1301, 53 USPQ2d 1065, 1069 (Fed. Cir. 1999) (meaning of words used in a claim is not construed in a “lexicographic vacuum, but in the context of the specification and drawings”). Thus, if a claim term is used in its ordinary and customary meaning throughout the specification, and the written description clearly indicates its meaning, then the term in the claim has that meaning. Old Town Canoe Co. v. Confluence Holdings Corp., 448 F.3d 1309, 1317, 78 USPQ2d 1705, 1711 (Fed. Cir. 2006) (The court held that “completion of coalescence” must be given its ordinary and customary meaning of reaching the end of coalescence. The court explained that even though coalescence could theoretically be “completed” by halting the molding process earlier, the specification clearly intended that completion of coalescence occurs only after the molding process reaches its optimum stage.).

However, it is important to note that any special meaning assigned to a term “must be sufficiently clear in the specification that any departure from common usage would be so understood by a person of experience in the field of the invention.” Multiform Desiccants Inc. v. Medzam Ltd., 133 F.3d 1473, 1477, 45 USPQ2d 1429, 1432 (Fed. Cir. 1998). See also Process Control Corp. v. HydReclaim Corp., 190 F.3d 1350, 1357, 52 USPQ2d 1029, 1033 (Fed. Cir. 1999) and MPEP § 2173.05(a).

In some cases, the meaning of a particular claim term may be defined by implication, that is, according to the usage of the term in the context in the specification. See Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1320-21, 75 USPQ2d 1321, 1332 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc); Vitronics Corp. v. Conceptronic Inc., 90 F.3d 1576, 1583, 39 USPQ2d 1573, 1577 (Fed. Cir. 1996). But where the specification is ambiguous as to whether the inventor used claim terms inconsistent with their ordinary meaning, the ordinary meaning will apply. Merck & Co. v. Teva Pharms. USA, Inc., 395 F.3d 1364, 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s construction of the claim term “about” as “exactly.” The appellate court explained that a passage in the specification the district court relied upon for the definition of “about” was too ambiguous to redefine “about” to mean “exactly” in clear enough terms. The appellate court held that “about” should instead be given its plain and ordinary meaning of “approximately.”).

B.DisavowalApplicant may also rebut the presumption of plain meaning by clearly disavowing the full scope of the claim term in the specification. Disavowal, or disclaimer of claim scope, is only considered when it is clear and unmistakable. See SciMed Life Sys., Inc. v. Advanced Cardiovascular Sys., Inc., 242 F.3d 1337, 1341, 58 USPQ2d 1059, 1063 (Fed.Cir.2001) (“Where the specification makes clear that the invention does not include a particular feature, that feature is deemed to be outside the reach of the claims of the patent, even though the language of the claims, read without reference to the specification, might be considered broad enough to encompass the feature in question.”); see also In re Am. Acad. Of Sci. Tech Ctr., 367 F.3d 1359, 1365-67 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (refusing to limit claim term “user computer” to only “single-user computers” even though “some of the language of the specification, when viewed in isolation, might lead a reader to conclude that the term . . . is meant to refer to a computer that serves only a single user, the specification as a whole suggests a construction that is not so narrow”). But, in some cases, disavowal of a broader claim scope may be made by implication, such as where the specification contains only disparaging remarks with respect to a feature and every embodiment in the specification excludes that feature. In re Abbott Diabetes Care Inc., 696 F.3d 1142, 1149-50, 104 USPQ2d 1337, 1342-43 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (holding that the broadest reasonable interpretation of the claim term “electrochemical sensor” does not include a sensor having “external connection cables or wires” because the specification “repeatedly, consistently, and exclusively depict[s] an electrochemical sensor without external cables or wires while simultaneously disparaging sensors with external cables or wires”). But see In re Clarke, 809 Fed. Appx. 787, 794, 2020 USPQ2d 10253 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (“The doctrine of prosecution history estoppel is inapplicable during prosecution. Instead the doctrine is applicable only to issued patents.”) (emphasis in the original). If the examiner believes that the broadest reasonable interpretation of a claim is narrower than what the words of the claim otherwise suggest as the result of implicit disavowal in the specification, then the examiner should make the interpretation clear on the record.

See also MPEP § 2173.05(a).

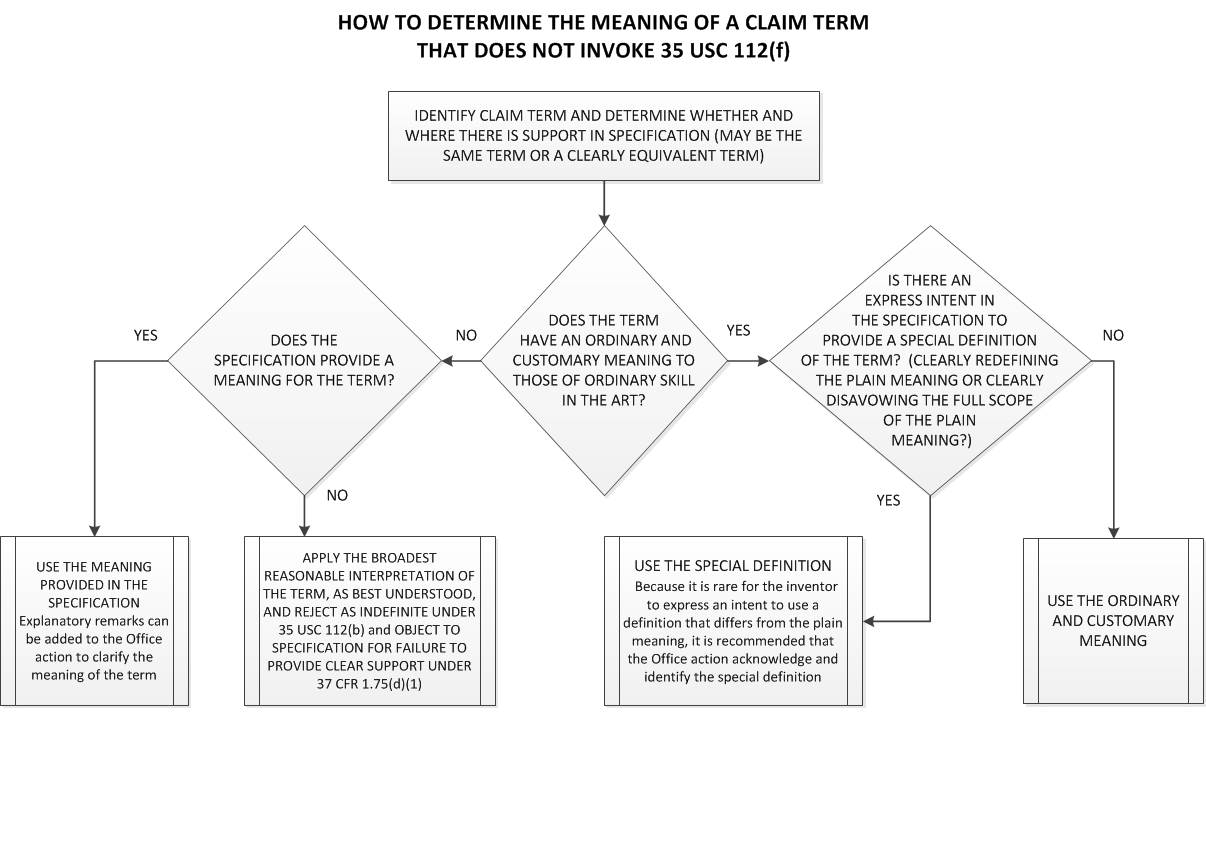

V. SUMMARY OF DETERMINING THE MEANING OF A CLAIM TERM THAT DOES NOT INVOKE 35 U.S.C. 112(f)This flow chart indicates the decisions an examiner would follow in order to ascertain the proper claim interpretation based on the plain meaning definition of BRI. With each decision in the flow chart, a different path may need to be taken to conclude whether plain meaning applies or a special definition applies.

The first question is to determine whether a claim term has an ordinary and customary meaning to those of ordinary skill in the art. If so, then the examiner should check the specification to determine whether it provides a special definition for the claim term. If the specification does not provide a special definition for the claim term, the examiner should apply the ordinary and customary meaning to the claim term. If the specification provides a special definition for the claim term, the examiner should use the special definition. However, because there is a presumption that claim terms have their ordinary and customary meaning and the specification must provide a clear and intentional use of a special definition for the claim term to be treated as having a special definition, an Office action should acknowledge and identify the special definition in this situation.

Moving back to the first question, if a claim term does not have an ordinary and customary meaning, the examiner should check the specification to determine whether it provides a meaning to the claim term. If no reasonably clear meaning can be ascribed to the claim term after considering the specification and prior art, the examiner should apply the broadest reasonable interpretation to the claim term as it can be best understood. Also, the claim should be rejected under 35 U.S.C. 112(b) and the specification objected to under 37 CFR 1.75(d).

If the specification provides a meaning for the claim term, the examiner should use the meaning provided by the specification. It may be appropriate for an Office action to acknowledge and identify the special definition in this situation.

2111.02 Effect of Preamble [R-07.2022]

The determination of whether a preamble limits a claim is made on a case-by-case basis in light of the facts in each case; there is no litmus test defining when a preamble limits the scope of a claim. Catalina Mktg. Int’l v. Coolsavings.com, Inc., 289 F.3d 801, 808, 62 USPQ2d 1781, 1785 (Fed. Cir. 2002). See id. at 808-10, 62 USPQ2d at 1784-86 for a discussion of guideposts that have emerged from various decisions exploring the preamble’s effect on claim scope, as well as a hypothetical example illustrating these principles.

“[A] claim preamble has the import that the claim as a whole suggests for it.” Bell Communications Research, Inc. v. Vitalink Communications Corp., 55 F.3d 615, 620, 34 USPQ2d 1816, 1820 (Fed. Cir. 1995). “If the claim preamble, when read in the context of the entire claim, recites limitations of the claim, or, if the claim preamble is ‘necessary to give life, meaning, and vitality’ to the claim, then the claim preamble should be construed as if in the balance of the claim.” Pitney Bowes, Inc. v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 182 F.3d 1298, 1305, 51 USPQ2d 1161, 1165-66 (Fed. Cir. 1999). See also Jansen v. Rexall Sundown, Inc., 342 F.3d 1329, 1333, 68 USPQ2d 1154, 1158 (Fed. Cir. 2003) (In considering the effect of the preamble in a claim directed to a method of treating or preventing pernicious anemia in humans by administering a certain vitamin preparation to “a human in need thereof,” the court held that the claims’ recitation of a patient or a human “in need” gives life and meaning to the preamble’s statement of purpose.). Kropa v. Robie, 187 F.2d 150, 152, 88 USPQ 478, 481 (CCPA 1951) (A preamble reciting “[a]n abrasive article” was deemed essential to point out the invention defined by claims to an article comprising abrasive grains and a hardened binder and the process of making it. The court stated “it is only by that phrase that it can be known that the subject matter defined by the claims is comprised as an abrasive article. Every union of substances capable inter alia of use as abrasive grains and a binder is not an ‘abrasive article.’” Therefore, the preamble served to further define the structure of the article produced.).

I. PREAMBLE STATEMENTS LIMITING STRUCTUREAny terminology in the preamble that limits the structure of the claimed invention must be treated as a claim limitation. See, e.g., Corning Glass Works v. Sumitomo Elec. U.S.A., Inc., 868 F.2d 1251, 1257, 9 USPQ2d 1962, 1966 (Fed. Cir. 1989) (The determination of whether preamble recitations are structural limitations can be resolved only on review of the entirety of the application “to gain an understanding of what the inventors actually invented and intended to encompass by the claim” as drafted without importing "'extraneous' limitations from the specification."); Pac-Tec Inc. v. Amerace Corp., 903 F.2d 796, 801, 14 USPQ2d 1871, 1876 (Fed. Cir. 1990) (determining that preamble language that constitutes a structural limitation is actually part of the claimed invention). See also In re Stencel, 828 F.2d 751, 4 USPQ2d 1071 (Fed. Cir. 1987) (The claim at issue was directed to a driver for setting a joint of a threaded collar; however, the body of the claim did not directly include the structure of the collar as part of the claimed article. The examiner did not consider the preamble, which did set forth the structure of the collar, as limiting the claim. The court found that the collar structure could not be ignored. While the claim was not directly limited to the collar, the collar structure recited in the preamble did limit the structure of the driver. “[T]he framework - the teachings of the prior art - against which patentability is measured is not all drivers broadly, but drivers suitable for use in combination with this collar, for the claims are so limited.” Id. at 1073, 828 F.2d at 754.).

II. PREAMBLE STATEMENTS RECITING PURPOSE OR INTENDED USEThe claim preamble must be read in the context of the entire claim. The determination of whether preamble recitations are structural limitations or mere statements of purpose or use “can be resolved only on review of the entirety of the [record] to gain an understanding of what the inventors actually invented and intended to encompass by the claim” as drafted without importing "'extraneous' limitations from the specification." Corning Glass Works, 868 F.2d at 1257, 9 USPQ2d at 1966. If the body of a claim fully and intrinsically sets forth all of the limitations of the claimed invention, and the preamble merely states, for example, the purpose or intended use of the invention, rather than any distinct definition of any of the claimed invention’s limitations, then the preamble is not considered a limitation and is of no significance to claim construction. Shoes by Firebug LLC v. Stride Rite Children’s Grp., LLC, 962 F.3d 1362, 2020 USPQ2d 10701 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (The court found that the preamble in one patent’s claim is limiting but is not in a related patent); Pitney Bowes, Inc. v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 182 F.3d 1298, 1305, 51 USPQ2d 1161, 1165 (Fed. Cir. 1999). See also Rowe v. Dror, 112 F.3d 473, 478, 42 USPQ2d 1550, 1553 (Fed. Cir. 1997) (“where a patentee defines a structurally complete invention in the claim body and uses the preamble only to state a purpose or intended use for the invention, the preamble is not a claim limitation”); Kropa v. Robie, 187 F.2d at 152, 88 USPQ2d at 480-81 (preamble is not a limitation where claim is directed to a product and the preamble merely recites a property inherent in an old product defined by the remainder of the claim); STX LLC. v. Brine, 211 F.3d 588, 591, 54 USPQ2d 1347, 1350 (Fed. Cir. 2000) (holding that the preamble phrase “which provides improved playing and handling characteristics” in a claim drawn to a head for a lacrosse stick was not a claim limitation). Compare Jansen v. Rexall Sundown, Inc., 342 F.3d 1329, 1333-34, 68 USPQ2d 1154, 1158 (Fed. Cir. 2003) (In a claim directed to a method of treating or preventing pernicious anemia in humans by administering a certain vitamin preparation to “a human in need thereof,” the court held that the preamble is not merely a statement of effect that may or may not be desired or appreciated, but rather is a statement of the intentional purpose for which the method must be performed. Thus the claim is properly interpreted to mean that the vitamin preparation must be administered to a human with a recognized need to treat or prevent pernicious anemia.); Nantkwest , Inc. v. Lee, 686 Fed. App'x 864, 867 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (nonprecedential) (The court found that the preamble phrase “treating a cancer” “’require[s] lysis of many cells, in order to accomplish the goal of treating cancer’ and not merely lysing one or a few cancer cells.”); In re Cruciferous Sprout Litig., 301 F.3d 1343, 1346-48, 64 USPQ2d 1202, 1204-05 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (A claim at issue was directed to a method of preparing a food rich in glucosinolates wherein cruciferous sprouts are harvested prior to the 2-leaf stage. The court held that the preamble phrase “rich in glucosinolates” helps define the claimed invention, as evidenced by the specification and prosecution history, and thus is a limitation of the claim (although the claim was anticipated by prior art that produced sprouts inherently “rich in glucosinolates”)).

During examination, statements in the preamble reciting the purpose or intended use of the claimed invention must be evaluated to determine whether or not the recited purpose or intended use results in a structural difference (or, in the case of process claims, manipulative difference) between the claimed invention and the prior art. If so, the recitation serves to limit the claim. See, e.g., In re Otto, 312 F.2d 937, 938, 136 USPQ 458, 459 (CCPA 1963) (The claims were directed to a core member for hair curlers and a process of making a core member for hair curlers. The court held that the intended use of hair curling was of no significance to the structure and process of making.); In re Sinex, 309 F.2d 488, 492, 135 USPQ 302, 305 (CCPA 1962) (statement of intended use in an apparatus claim did not distinguish over the prior art apparatus). To satisfy an intended use limitation which is limiting, a prior art structure which is capable of performing the intended use as recited in the preamble meets the claim. See, e.g., In re Schreiber, 128 F.3d 1473, 1477, 44 USPQ2d 1429, 1431 (Fed. Cir. 1997) (anticipation rejection affirmed based on Board’s factual finding that the reference dispenser (a spout disclosed as useful for purposes such as dispensing oil from an oil can) would be capable of dispensing popcorn in the manner set forth in appellant’s claim 1 (a dispensing top for dispensing popcorn in a specified manner)) and cases cited therein. See also MPEP § 2112 - MPEP § 2112.02.

However, a “preamble may provide context for claim construction, particularly, where … that preamble’s statement of intended use forms the basis for distinguishing the prior art in the patent’s prosecution history.” Metabolite Labs., Inc. v. Corp. of Am. Holdings, 370 F.3d 1354, 1358-62, 71 USPQ2d 1081, 1084-87 (Fed. Cir. 2004). The patent claim at issue was directed to a two-step method for detecting a deficiency of vitamin B12 or folic acid, involving (i) assaying a body fluid for an “elevated level” of homocysteine, and (ii) “correlating” an “elevated” level with a vitamin deficiency. Id. at 1358-59, 71 USPQ2d at 1084. The court stated that the disputed claim term “correlating” can include comparing with either an unelevated level or elevated level, as opposed to only an elevated level because adding the “correlating” step in the claim during prosecution to overcome prior art tied the preamble directly to the “correlating” step. Id. at 1362, 71 USPQ2d at 1087. The recitation of the intended use of “detecting” a vitamin deficiency in the preamble rendered the claimed invention a method for “detecting,” and, thus, was not limited to detecting “elevated” levels. Id.

See also Catalina Mktg. Int’l, 289 F.3d at 808-09, 62 USPQ2d at 1785 (“[C]lear reliance on the preamble during prosecution to distinguish the claimed invention from the prior art transforms the preamble into a claim limitation because such reliance indicates use of the preamble to define, in part, the claimed invention.…Without such reliance, however, a preamble generally is not limiting when the claim body describes a structurally complete invention such that deletion of the preamble phrase does not affect the structure or steps of the claimed invention.” Consequently, “preamble language merely extolling benefits or features of the claimed invention does not limit the claim scope without clear reliance on those benefits or features as patentably significant.”). In Poly-America LP v. GSE Lining Tech. Inc., 383 F.3d 1303, 1310, 72 USPQ2d 1685, 1689 (Fed. Cir. 2004), the court stated that “a ‘[r]eview of the entirety of the ’047 patent reveals that the preamble language relating to ‘blown-film’ does not state a purpose or an intended use of the invention, but rather discloses a fundamental characteristic of the claimed invention that is properly construed as a limitation of the claim.’” Compare Intirtool, Ltd. v. Texar Corp., 369 F.3d 1289, 1294-96, 70 USPQ2d 1780, 1783-84 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (holding that the preamble of a patent claim directed to a “hand-held punch pliers for simultaneously punching and connecting overlapping sheet metal” was not a limitation of the claim because (i) the body of the claim described a “structurally complete invention” without the preamble, and (ii) statements in prosecution history referring to “punching and connecting” function of invention did not constitute “clear reliance” on the preamble needed to make the preamble a limitation).

2111.03 Transitional Phrases [R-07.2022]

The transitional phrases “comprising”, “consisting essentially of” and “consisting of” define the scope of a claim with respect to what unrecited additional components or steps, if any, are excluded from the scope of the claim. The determination of what is or is not excluded by a transitional phrase must be made on a case-by-case basis in light of the facts of each case.

I. COMPRISINGThe transitional term “comprising”, which is synonymous with “including,” “containing,” or “characterized by,” is inclusive or open-ended and does not exclude additional, unrecited elements or method steps. See, e.g., Mars Inc. v. H.J. Heinz Co., 377 F.3d 1369, 1376, 71 USPQ2d 1837, 1843 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (“[L]ike the term ‘comprising,’ the terms ‘containing’ and ‘mixture’ are open-ended.”). Invitrogen Corp. v. Biocrest Manufacturing, L.P., 327 F.3d 1364, 1368, 66 USPQ2d 1631, 1634 (Fed. Cir. 2003) (“The transition ‘comprising’ in a method claim indicates that the claim is open-ended and allows for additional steps.”); Genentech, Inc. v. Chiron Corp., 112 F.3d 495, 501, 42 USPQ2d 1608, 1613 (Fed. Cir. 1997) (“Comprising” is a term of art used in claim language which means that the named elements are essential, but other elements may be added and still form a construct within the scope of the claim.); Moleculon Research Corp.v.CBS, Inc., 793 F.2d 1261, 229 USPQ 805 (Fed. Cir. 1986); In re Baxter, 656 F.2d 679, 686, 210 USPQ 795, 803 (CCPA 1981); Ex parte Davis, 80 USPQ 448, 450 (Bd. App. 1948) (“comprising” leaves “the claim open for the inclusion of unspecified ingredients even in major amounts”). In Gillette Co. v. Energizer Holdings Inc., 405 F.3d 1367, 1371-73, 74 USPQ2d 1586, 1589-91 (Fed. Cir. 2005), the court held that a claim to “a safety razor blade unit comprising a guard, a cap, and a group of first, second, and third blades” encompasses razors with more than three blades because the transitional phrase “comprising” in the preamble and the phrase “group of” are presumptively open-ended. “The word ‘comprising’ transitioning from the preamble to the body signals that the entire claim is presumptively open-ended.” Id. In contrast, the court noted the phrase “group consisting of” is a closed term, which is often used in claim drafting to signal a “Markush group” that is by its nature closed. Id. The court also emphasized that reference to “first,” “second,” and “third” blades in the claim was not used to show a serial or numerical limitation but instead was used to distinguish or identify the various members of the group. Id.

II. CONSISTING OFThe transitional phrase “consisting of” excludes any element, step, or ingredient not specified in the claim. In re Gray, 53 F.2d 520, 11 USPQ 255 (CCPA 1931); Ex parte Davis, 80 USPQ 448, 450 (Bd. App. 1948) (“consisting of” defined as “closing the claim to the inclusion of materials other than those recited except for impurities ordinarily associated therewith”). But see Norian Corp. v. Stryker Corp., 363 F.3d 1321, 1331-32, 70 USPQ2d 1508, 1516 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (holding that a bone repair kit "consisting of" claimed chemicals was infringed by a bone repair kit including a spatula in addition to the claimed chemicals because the presence of the spatula was unrelated to the claimed invention). A claim which depends from a claim which “consists of” the recited elements or steps cannot add an element or step.

When the phrase “consists of” appears in a clause of the body of a claim, rather than immediately following the preamble, there is an “exceptionally strong presumption that a claim term set off with ‘consisting of’ is closed to unrecited elements.” Multilayer Stretch Cling Film Holdings, Inc. v. Berry Plastics Corp., 831 F.3d 1350, 1359, 119 USPQ2d 1773, 1781 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (a layer “selected from the group consisting of” specific resins is closed to resins other than those listed). However, the “consisting of” phrase limits only the element set forth in that clause; other elements are not excluded from the claim as a whole. Mannesmann Demag Corp.v.Engineered Metal Products Co., 793 F.2d 1279, 230 USPQ 45 (Fed. Cir. 1986). See also In re Crish, 393 F.3d 1253, 73 USPQ2d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (The claims at issue “related to purified DNA molecules having promoter activity for the human involucrin gene (hINV).” Id., 73 USPQ2d at 1365. In determining the scope of applicant’s claims directed to “a purified oligonucleotide comprising at least a portion of the nucleotide sequence of SEQ ID NO:1 wherein said portion consists of the nucleotide sequence from … to 2473 of SEQ ID NO:1, and wherein said portion of the nucleotide sequence of SEQ ID NO:1 has promoter activity,” the court stated that the use of “consists” in the body of the claims did not limit the open-ended “comprising” language in the claims (emphases added). Id. at 1257, 73 USPQ2d at 1367. The court held that the claimed promoter sequence designated as SEQ ID NO:1 was obtained by sequencing the same prior art plasmid and was therefore anticipated by the prior art plasmid which necessarily possessed the same DNA sequence as the claimed oligonucleotides. Id. at 1256 and 1259, 73 USPQ2d at 1366 and 1369. The court affirmed the Board’s interpretation that the transition phrase “consists” did not limit the claims to only the recited numbered nucleotide sequences of SEQ ID NO:1 and that “the transition language ‘comprising’ allowed the claims to cover the entire involucrin gene plus other portions of the plasmid, as long as the gene contained the specific portions of SEQ ID NO:1 recited by the claim[s].” Id. at 1256, 73 USPQ2d at 1366.).

A claim element defined by selection from a group of alternatives (a Markush grouping; see MPEP § 2117 and § 2173.05(h)) requires selection from a closed group “consisting of” (rather than “comprising” or “including”) the alternative members. Abbott Labs. v. Baxter Pharmaceutical Products Inc., 334 F.3d 1274, 1280, 67 USPQ2d 1191, 1196-97 (Fed. Cir. 2003). If the claim element is intended to encompass combinations or mixtures of the alternatives set forth in the Markush grouping, the claim may include qualifying language preceding the recited alternatives (such as “at least one member” selected from the group), or within the list of alternatives (such as “or mixtures thereof”). Id. In the absence of such qualifying language there is a presumption that the Markush group is closed to combinations or mixtures. See Multilayer Stretch Cling Film Holdings, Inc. v. Berry Plastics Corp., 831 F.3d 1350, 1363-64, 119 USPQ2d 1773, 1784-85 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (presumption that Markush grouping does not encompass mixtures of listed resins overcome by intrinsic evidence in a dependent claim and the specification).

III. CONSISTING ESSENTIALLY OFThe transitional phrase “consisting essentially of” limits the scope of a claim to the specified materials or steps “and those that do not materially affect the basic and novel characteristic(s)” of the claimed invention. In re Herz, 537 F.2d 549, 551-52, 190 USPQ 461, 463 (CCPA 1976) (emphasis in original) (Prior art hydraulic fluid required a dispersant which appellants argued was excluded from claims limited to a functional fluid “consisting essentially of” certain components. In finding the claims did not exclude the prior art dispersant, the court noted that appellants’ specification indicated the claimed composition can contain any well-known additive such as a dispersant, and there was no evidence that the presence of a dispersant would materially affect the basic and novel characteristic of the claimed invention. The prior art composition had the same basic and novel characteristic (increased oxidation resistance) as well as additional enhanced detergent and dispersant characteristics.). “A ‘consisting essentially of’ claim occupies a middle ground between closed claims that are written in a ‘consisting of’ format and fully open claims that are drafted in a ‘comprising’ format.” PPG Industries v. Guardian Industries, 156 F.3d 1351, 1354, 48 USPQ2d 1351, 1353-54 (Fed. Cir. 1998). See also Atlas Powder v. E.I. duPont de Nemours & Co., 750 F.2d 1569, 224 USPQ 409 (Fed. Cir. 1984); In re Janakirama-Rao, 317 F.2d 951, 137 USPQ 893 (CCPA 1963); Water Technologies Corp. vs. Calco, Ltd., 850 F.2d 660, 7 USPQ2d 1097 (Fed. Cir. 1988). For the purposes of searching for and applying prior art under 35 U.S.C. 102 and 103, absent a clear indication in the specification or claims of what the basic and novel characteristics actually are, “consisting essentially of” will be construed as equivalent to “comprising.” See, e.g., PPG, 156 F.3d at 1355, 48 USPQ2d at 1355 (“PPG could have defined the scope of the phrase ‘consisting essentially of’ for purposes of its patent by making clear in its specification what it regarded as constituting a material change in the basic and novel characteristics of the invention.”). See also AK Steel Corp. v. Sollac, 344 F.3d 1234, 1240-41, 68 USPQ2d 1280, 1283-84 (Fed. Cir. 2003) (Applicant’s statement in the specification that “silicon contents in the coating metal should not exceed about 0.5% by weight” along with a discussion of the deleterious effects of silicon provided basis to conclude that silicon in excess of 0.5% by weight would materially alter the basic and novel properties of the invention. Thus, “consisting essentially of” as recited in the preamble was interpreted to permit no more than 0.5% by weight of silicon in the aluminum coating.); In re Janakirama-Rao, 317 F.2d 951, 954, 137 USPQ 893, 895-96 (CCPA 1963). If an applicant contends that additional steps or materials in the prior art are excluded by the recitation of “consisting essentially of,” applicant has the burden of showing that the introduction of additional steps or components would materially change the characteristics of the claimed invention. In re De Lajarte, 337 F.2d 870, 143 USPQ 256 (CCPA 1964). See also Ex parte Hoffman, 12 USPQ2d 1061, 1063-64 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1989) (“Although ‘consisting essentially of’ is typically used and defined in the context of compositions of matter, we find nothing intrinsically wrong with the use of such language as a modifier of method steps. . . [rendering] the claim open only for the inclusion of steps which do not materially affect the basic and novel characteristics of the claimed method. To determine the steps included versus excluded the claim must be read in light of the specification. . . . [I]t is an applicant’s burden to establish that a step practiced in a prior art method is excluded from his claims by ‘consisting essentially of’ language.”).

IV. OTHER TRANSITIONAL PHRASESTransitional phrases such as “having” must be interpreted in light of the specification to determine whether open or closed claim language is intended. See, e.g., Lampi Corp. v. American Power Products Inc., 228 F.3d 1365, 1376, 56 USPQ2d 1445, 1453 (Fed. Cir. 2000) (interpreting the term “having” as open terminology, allowing the inclusion of other components in addition to those recited); Crystal Semiconductor Corp. v. TriTech Microelectronics Int’l Inc., 246 F.3d 1336, 1348, 57 USPQ2d 1953, 1959 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (term “having” in transitional phrase “does not create a presumption that the body of the claim is open”); Regents of the Univ. of Cal. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 119 F.3d 1559, 1573, 43 USPQ2d 1398, 1410 (Fed. Cir. 1997) (in the context of a cDNA having a sequence coding for human PI, the term “having” still permitted inclusion of other moieties). The transitional phrase “composed of” has been interpreted in the same manner as either “consisting of” or “consisting essentially of,” depending on the facts of the particular case. See AFG Industries, Inc. v. Cardinal IG Company, 239 F.3d 1239, 1245, 57 USPQ2d 1776, 1780-81 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (based on specification and other evidence, “composed of” interpreted in same manner as “consisting essentially of”); In re Bertsch, 132 F.2d 1014, 1019-20, 56 USPQ 379, 384 (CCPA 1942) (“Composed of” interpreted in same manner as “consisting of”; however, the court further remarked that “the words ‘composed of’ may under certain circumstances be given, in patent law, a broader meaning than ‘consisting of.’”).

2111.04 “Adapted to,” “Adapted for,” “Wherein,” “Whereby,” and Contingent Clauses [R-10.2019]

I. “ADAPTED TO,” “ADAPTED FOR,” “WHEREIN," and "WHEREBY”Claim scope is not limited by claim language that suggests or makes optional but does not require steps to be performed, or by claim language that does not limit a claim to a particular structure. However, examples of claim language, although not exhaustive, that may raise a question as to the limiting effect of the language in a claim are:

- (A) “adapted to” or “adapted for” clauses;

- (B) “wherein” clauses; and

- (C) “whereby” clauses.

The determination of whether each of these clauses is a limitation in a claim depends on the specific facts of the case. See, e.g., Griffin v. Bertina, 285 F.3d 1029, 1034, 62 USPQ2d 1431 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (finding that a “wherein” clause limited a process claim where the clause gave “meaning and purpose to the manipulative steps”). In In re Giannelli, 739 F.3d 1375, 1378, 109 USPQ2d 1333, 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2014), the court found that an "adapted to" clause limited a machine claim where "the written description makes clear that 'adapted to,' as used in the [patent] application, has a narrower meaning, viz., that the claimed machine is designed or constructed to be used as a rowing machine whereby a pulling force is exerted on the handles." In Hoffer v. Microsoft Corp., 405 F.3d 1326, 1329, 74 USPQ2d 1481, 1483 (Fed. Cir. 2005), the court held that when a “‘whereby’ clause states a condition that is material to patentability, it cannot be ignored in order to change the substance of the invention.” Id. However, the court noted that a “‘whereby clause in a method claim is not given weight when it simply expresses the intended result of a process step positively recited.’” Id. (quoting Minton v. Nat’l Ass’n of Securities Dealers, Inc., 336 F.3d 1373, 1381, 67 USPQ2d 1614, 1620 (Fed. Cir. 2003)).

II. CONTINGENT LIMITATIONSThe broadest reasonable interpretation of a method (or process) claim having contingent limitations requires only those steps that must be performed and does not include steps that are not required to be performed because the condition(s) precedent are not met. For example, assume a method claim requires step A if a first condition happens and step B if a second condition happens. If the claimed invention may be practiced without either the first or second condition happening, then neither step A or B is required by the broadest reasonable interpretation of the claim. If the claimed invention requires the first condition to occur, then the broadest reasonable interpretation of the claim requires step A. If the claimed invention requires both the first and second conditions to occur, then the broadest reasonable interpretation of the claim requires both steps A and B.

The broadest reasonable interpretation of a system (or apparatus or product) claim having structure that performs a function, which only needs to occur if a condition precedent is met, requires structure for performing the function should the condition occur. The system claim interpretation differs from a method claim interpretation because the claimed structure must be present in the system regardless of whether the condition is met and the function is actually performed.

See Ex parte Schulhauser, Appeal 2013-007847 (PTAB April 28, 2016) for an analysis of contingent claim limitations in the context of both method claims and system claims. In Schulhauser, both method claims and system claims recited the same contingent step. When analyzing the claimed method as a whole, the PTAB determined that giving the claim its broadest reasonable interpretation, “[i]f the condition for performing a contingent step is not satisfied, the performance recited by the step need not be carried out in order for the claimed method to be performed” (quotation omitted). Schulhauser at 10. When analyzing the claimed system as a whole, the PTAB determined that “[t]he broadest reasonable interpretation of a system claim having structure that performs a function, which only needs to occur if a condition precedent is met, still requires structure for performing the function should the condition occur.” Schulhauser at 14. Therefore "[t]he Examiner did not need to present evidence of the obviousness of the [ ] method steps of claim 1 that are not required to be performed under a broadest reasonable interpretation of the claim (e.g., instances in which the electrocardiac signal data is not within the threshold electrocardiac criteria such that the condition precedent for the determining step and the remaining steps of claim 1 has not been met);" however to render the claimed system obvious, the prior art must teach the structure that performs the function of the contingent step along with the other recited claim limitations. Schulhauser at 9, 14.

See also MPEP § 2143.03.

2111.05 Functional and Nonfunctional Descriptive Material [R-07.2022]

USPTO personnel must consider all claim limitations when determining patentability of an invention over the prior art. In re Gulack, 703 F.2d 1381, 1385, 217 USPQ 401, 403-04 (Fed. Cir. 1983). Since a claim must be read as a whole, USPTO personnel may not disregard claim limitations that include printed matter. See Id. at 1384, 217 USPQ at 403; see also Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 191, 209 USPQ 1, 10 (1981). The first step of the printed matter analysis is the determination that the limitation in question is in fact directed toward printed matter. “Our past cases establish a necessary condition for falling into the category of printed matter: a limitation is printed matter only if it claims the content of information.” See In re DiStefano, 808 F.3d 845, 848, 117 USPQ2d 1265, 1267 (Fed. Cir. 2015). “[O]nce it is determined that the limitation is directed to printed matter, [the examiner] must then determine if the matter is functionally or structurally related to the associated physical substrate, and only if the answer is ‘no’ is the printed matter owed no patentable weight.” Id. at 850, 117 USPQ2d at 1268. If a new and nonobvious functional relationship between the printed matter and the substrate does exist, the examiner should give patentable weight to printed matter. See In re Lowry, 32 F.3d 1579, 1583-84, 32 USPQ2d 1031, 1035 (Fed. Cir. 1994); In re Ngai, 367 F.3d 1336, 70 USPQ2d 1862 (Fed. Cir. 2004); In re Gulack, 703 F.2d 1381, 1385, 217 USPQ 401, 403-04 (Fed. Cir. 1983). The rationale behind the printed matter cases, in which, for example, written instructions are added to a known product, has been extended to method claims in which an instructional limitation is added to a method known in the art. Similar to the inquiry for products with printed matter thereon, in such method cases the relevant inquiry is whether a new and nonobvious functional relationship with the known method exists. See In re DiStefano, 808 F.3d 845, 117 USPQ2d 1265 (Fed. Cir. 2015); In re Kao, 639 F.3d 1057, 1072-73, 98 USPQ2d 1799, 1811-12 (Fed. Cir. 2011); King Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Eon Labs Inc., 616 F.3d 1267, 1279, 95 USPQ2d 1833, 1842 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

I. DETERMINING WHETHER A FUNCTIONAL RELATIONSHIP EXISTS BETWEEN PRINTED MATTER AND ASSOCIATED SUBSTRATETo be given patentable weight, the printed matter and associated product must be in a functional relationship. A functional relationship can be found where the printed matter performs some function with respect to the product to which it is associated. See Lowry, 32 F.3d at 1584, 32 USPQ2d at 1035 (citing Gulack, 703 F.2d at 1386, 217 USPQ at 404). For instance, indicia on a measuring cup perform the function of indicating volume within that measuring cup. See In re Miller, 418 F.2d 1392, 1396, 164 USPQ 46, 49 (CCPA 1969). A functional relationship can also be found where the product performs some function with respect to the printed matter to which it is associated. For instance, where a hatband places a string of numbers in a certain physical relationship to each other such that a claimed algorithm is satisfied due to the physical structure of the hatband, the hatband performs a function with respect to the string of numbers. See Gulack, 703 F.2d at 1386-87, 217 USPQ at 405.

B.Evidence Against a Functional RelationshipWhere a product merely serves as a support for printed matter, no functional relationship exists. These situations may arise where the claim as a whole is directed towards conveying a message or meaning to a human reader independent of the supporting product. For example, a hatband with images displayed on the hatband but not arranged in any particular sequence was found to only serve as support and display for the printed matter. See Gulack, 703 F.2d at 1386, 217 USPQ at 404. Another example in which a product merely serves as a support would occur for a deck of playing cards having images on each card. See In re Bryan, 323 Fed. App'x 898 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (unpublished). In Bryan the applicant asserted that the printed matter allowed the cards to be “collected, traded, and drawn”; “identify and distinguish one deck of cards from another”; and “enable[] the card to be traded and blind drawn”. However, the court found that these functions do not pertain to the structure of the apparatus and were instead drawn to the method or process of playing a game. See also Ex parte Gwinn, 112 USPQ 439, 446-47 (Bd. Pat. App. & Int. 1955), in which the invention was directed to a set of dice by means of which a game may be played. The claims differed from the prior art solely by the printed matter in the dice. The claims were properly rejected on prior art because there was no new feature of physical structure and no new relation of printed matter to physical structure. For example, a claimed measuring tape having electrical wiring information thereon, or a generically claimed substrate having a picture of a golf ball thereupon, would lack a functional relationship as the claims as a whole are directed towards conveying wiring information (unrelated to the measuring tape) or an aesthetically pleasing image (unrelated to the substrate) to the reader. Additionally, where the printed matter and product do not depend upon each other, no functional relationship exists. For example, in a kit containing a set of chemicals and a printed set of instructions for using the chemicals, the instructions are not related to that particular set of chemicals. In re Ngai, 367 F.3d at 1339, 70 USPQ2d at 1864.

II. FUNCTIONAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PRINTED MATTER AND ASSOCIATED SUBSTRATE MUST BE NEW AND NONOBVIOUSOnce a functional relationship between the product and associated printed matter is found, the investigation shifts to the determination of whether the relationship is new and nonobvious. For example, a claim to a color-coded indicia on a container in which the color indicates the expiration date of the container may give rise to a functional relationship. The claim may, however, be anticipated by prior art that reads on the claimed invention, or by a combination of prior art that teaches the claimed invention.

III. MACHINE-READABLE MEDIAWhen determining the scope of a claim directed to a computer-readable medium containing certain programming, the examiner should first look to the relationship between the programming and the intended computer system. Where the programming performs some function with respect to the computer with which it is associated, a functional relationship will be found. For instance, a claim to computer-readable medium programmed with attribute data objects that perform the function of facilitating retrieval, addition, and removal of information in the intended computer system, establishes a functional relationship such that the claimed attribute data objects are given patentable weight. See Lowry, 32 F.3d at 1583-84, 32 USPQ2d at 1035.

However, where the claim as a whole is directed to conveying a message or meaning to a human reader independent of the intended computer system, and/or the computer-readable medium merely serves as a support for information or data, no functional relationship exists. For example, a claim to a memory stick containing tables of batting averages, or tracks of recorded music, utilizes the intended computer system merely as a support for the information. Such claims are directed toward conveying meaning to the human reader rather than towards establishing a functional relationship between recorded data and the computer.

A claim directed to a computer readable medium storing instructions or executable code that recites an abstract idea must be evaluated for eligibility under 35 U.S.C. 101. See MPEP § 2106.