A solar life

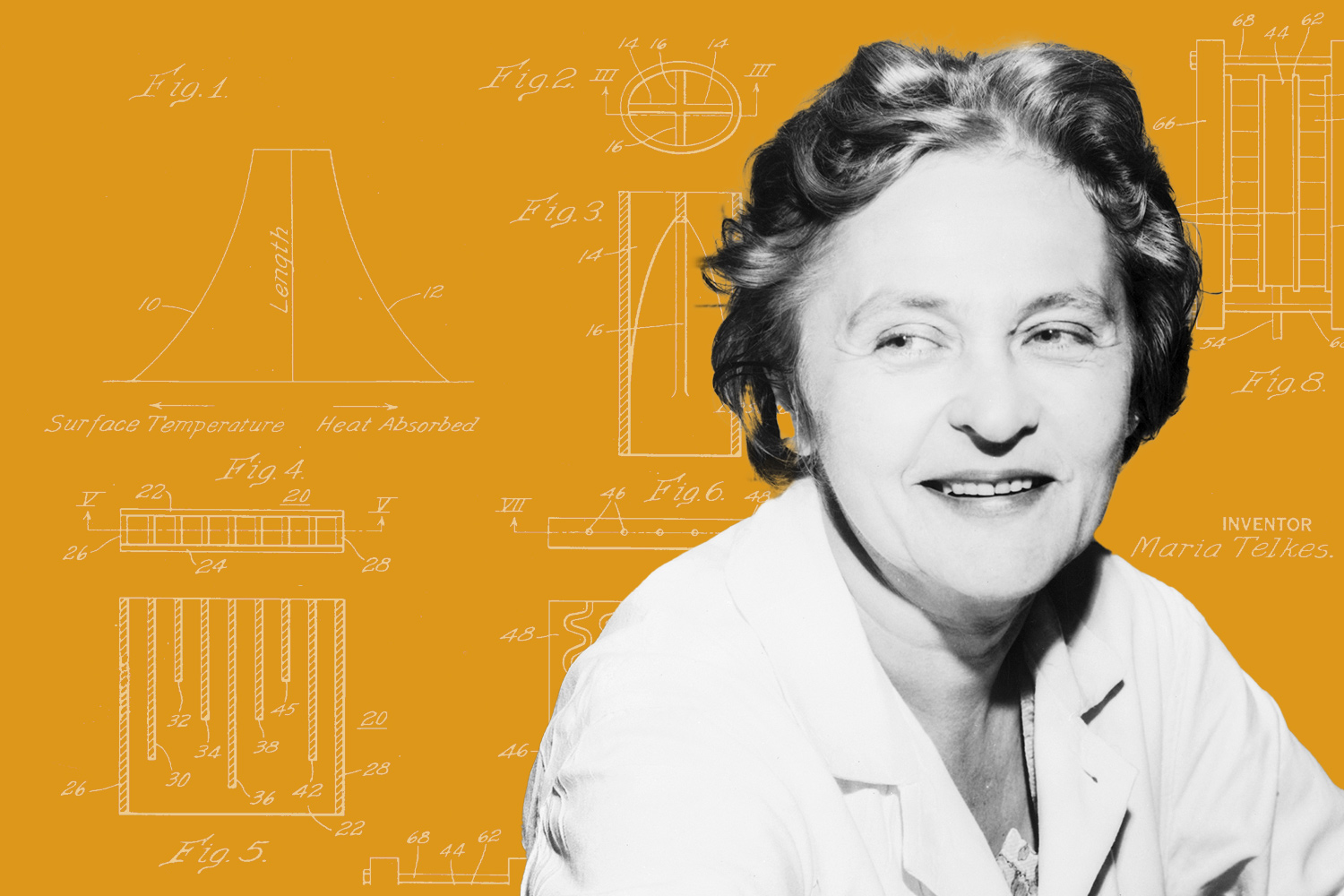

Known as the “Sun Queen” for her lifelong promotion of solar heating, Maria Telkes was a press-friendly public intellectual who appeared on TV and in countless newspaper stories and magazine articles, but she struggled to have her aspirations and work taken seriously by her colleagues and collaborators throughout her career.

23 min read

Each month, our Journeys of Innovation series tells the stories of inventors or entrepreneurs who have made a positive difference in the world. This month, Axel Alfaro-Hernandez's story focuses on Dr. Maria Telkes, an avid advocate for solar heating who used the media to promote its use despite pushback from colleagues.

Do you know an innovator or entrepreneur with an interesting story?

With a prism-shaped aluminum box tucked under her arm, 54-year-old scientist Maria Telkes walks across the campus of New York University (NYU) toward a group of faculty members and students who had gathered outside under the mid-day sun. Making her way to the center of the group, she sets the box down, slips on four shiny metal sheets and pops in some burger patties. Soon, the fat from the burgers begins to sizzle, the meaty aroma wafts outward, and the surrounding stomachs start to rumble. Thirty-five minutes later, crispy brown burgers await the hungry crowd — cooked entirely by the sun.

Lunchtime.

“It will bake, broil, roast, and toast. Everything except whistle,” Dr. Telkes joked to a journalist about this latest invention of hers, the solar oven.

At this point in her career, in 1955, Telkes was called “The Sun Queen” for a reason. The public had watched her promote solar energy in TV shows and read about her work in print. Now, after decades of speaking theoretically about the usefulness of the sun, she enjoyed showing off the tangible benefits of solar energy — cooking food using nothing but the sun.

Telkes’ solar oven was something different from her previous work, but it had drawn her closer than ever to her vision of the future — one of universally accessible and affordable energy — that had led her to the United States in the first place.

Born in Hungary, Telkes developed an interest in chemistry as a child. At age 11, a school experiment she observed led her to set up a “laboratory” inside her parents’ garden-house in Budapest. Telkes’ at-home experimentation, including one ”loud but harmless explosion,” was thankfully tolerated by her amused parents. Her passion for science eventually led her to pursue higher education despite the fact that only 14% of university students in Hungary were women.

As a freshman at the University of Budapest, Telkes read a book on alternative energy sources that ignited her lifelong fascination with solar energy and defined her career moving forward.

“The book explained that the usual energy sources have geographical limitations, especially in the less-developed tropical regions, but the sun is directly overhead in the tropics, and you do not have to explore for it,” she recalled later.

She pictured a day when people in developing countries would have access to free energy to satisfy their basic needs, and she wanted to make it a reality.

Telkes obtained a doctoral degree in physical chemistry in 1924 and served as an instructor for a time at the university before immigrating to the United States — then a leader in solar energy research. In 1928, she took a job as a biophysicist at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, a nonprofit academic medical center founded just seven years prior.

For nearly a decade, Telkes assisted surgeon, scientist, and clinic co-founder Dr. George Washington Crile with projects like using dead organic matter to create synthetic cells that could theoretically help scientists better understand cancer cells.

It was there that she had her first encounters with the media. Initially attracted by the foundation’s research, journalistic focus quickly shifted away from the science to the superficial — an indication of things to come.

In 1932, syndicated columnist Arthur Brisbane, described by newspaper editors at the time as “the most highly paid and most widely read editorial writer in the world,” traveled to the clinic to write about Telkes’ workplace.

Instead of focusing on the work Telkes and her colleagues were doing on the cellular level, Brisbane’s column commented at length on Telkes’ physical attributes, disposition, and his failed attempt to charm the scientist.

Brisbane describes Telkes as a “youthful and beautiful Hungarian highbrow” with a “deep voice” but does not similarly describe her male counterparts’ physical characteristics, reflecting the deeply engrained gender biases of the time.

Throughout her life, Telkes would encounter this double standard when dealing with journalists, who would describe her as an “attractive blonde,” “a noted and attractive Hungarian scientist,” “a burn-haired scientist,” and “vivacious and charming but completely inaccessible.” Not one to be deterred, as she demonstrated many times in life, Telkes learned to leverage these, at best, superficial, interactions into vital experiences and insights more generally about the press and media, that would help her promote her work and vision later in her career.

Maria Telkes labeled this picture from 1953 "Leaving MIT." Her demeanor in the picture contrasts with her usual cheerful disposition. She would overcome objections from colleagues throughout her career to become a pioneer in solar energy. She was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2012.

(Courtesy of Maria Telkes Papers, Design and the Arts Special Collections, Arizona State University Library)

During her employment at the Cleveland Clinic, Telkes continued her work on solar energy in her free time by developing a device called a thermopile to convert sunlight into electricity. By 1934, her work had caught enough attention that one newspaper named her one of the most interesting women of the year. Telkes was the only scientist recognized, alongside more conventional celebrities like athletes, socialites, and child actress Shirley Temple.

In 1937 — the year she became an American citizen — Telkes moved on to Westinghouse, where she landed a role as a research engineer working on turning heat into electricity. While there, in April 1938, she heard about a new initiative at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the Solar Energy Conversion Project. The project aimed to bring together the best scientists working on solar energy, and Telkes was immediately intrigued. It was the type of ambitious program she might have pictured when reading about American solar energy experiments as a student in Hungary.

Telkes wrote to university leaders and asked them for the opportunity to interview. However, she did not trust that her growing reputation would be enough to get her the job. When she wasn’t offered a position, she traveled to Massachusetts and presented her thermopile prototype to the all-male committee, which she estimated to be ten times more efficient at turning sunlight into power than any existing technology. In July 1939, she was finally invited to join the program, where she would be working for scientist Hoyt Hottel.

A peculiar choice to lead the project, Hottel was a chemical engineering professor who seemed highly doubtful of the potential of solar power as a reliable source of energy. Decades later, in 1977, he would say that solar-heating advocates like Telkes, ”base their case on emotion, not on natural law.”

Soon after Telkes joined the project, in 1941, the United States’ entry into World War II shifted the research team’s priorities. The war unleashed an unprecedented energy crisis, with supply shortages from increased wartime demand exacerbated by German U-boat attacks on oil tankers. Under these pressing circumstances, the MIT team’s efforts were redirected toward the war. Telkes became a civilian advisor to the U.S. government’s Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD).

Telkes, specifically, was asked to use her energy expertise in an especially unconventional way — one that could save American service members’ lives. It wasn’t uncommon for air crews who were shot down over the open ocean to survive the crash, only to later succumb to dehydration before they could be rescued, surrounded by water they could not drink.

According to Telkes, a solution came to her while she was sailing with a friend. Seeing a big jellyfish, she had the idea for her first solar-power invention, an inflatable desalination kit called a solar still. It allowed a person to collect sea water inside a balloon-like plastic envelope that fit in a paper-cup size package when empty. When the sea water evaporated, it was separated from the salt in it, leaving only drinkable water once it condensed again.

U.S. service members show how to use Telkes’ solar stills to make sea water drinkable. In one of the final parts of the process, the balloon-like containers are left under the sun so the sea water will evaporate.

(Courtesy of Maria Telkes Papers, Design and the Arts Special Collections, Arizona State University Library)

The U.S. government liked Telkes’ idea and ordered 100,000 solar stills, but by the summer of 1945, MIT had delivered none of them. As a PBS documentary explained, “At MIT, Hoyt Hottel, ever the perfectionist, kept switching manufacturers and quibbling with Telkes over design details — unwilling to commit until he believed his exacting standards had been met.”

Gender studies scholar Olivia Meikle further summed up the contrast between Hottel and Telkes in the same documentary, noting:

“For Hoyt Hottel, science is about knowledge. He's very interested in big, important academic ideas, but he is not very interested in how any of these things might apply in the world. Whereas for Maria Telkes, science is about making lives better, making the world better. She is interested in science from a humanitarian perspective.”

While Hottel’s perceived perfectionism prevented Telkes’ invention from being used during the war, the solar stills did eventually end up in military emergency kits — likely contributing to safer military operations for years following. Telkes eventually received patent no. 3,415,719 for this invention.

After completing her OSRD assignment, Telkes returned to her lifelong pursuit of harnessing solar energy. Although the war was over, the scarcities and sense of energy insecurity it had created remained in the social conscience. The conditions were favorable for Telkes to gather support for solar, but first she had to crack the two main problems surrounding it: how to efficiently convert sunlight into other forms of energy and how to store that energy once converted. Without answering these questions, solar energy would never be efficient and cheap enough to supplant other forms of energy in everyday life. Unfortunately, solutions had proven so elusive that some compared storing the sun’s heat to mythical fantasies like perpetual motion machines or alchemy.

Telkes eventually devised a clever potential solution: a solar house that would use a substance called sodium sulfate, also known as Glauber’s Salt, as its heating element. Containers of sodium sulfate behind a glass wall would absorb heat during daytime and release it when the building cooled at night.

Despite intense skepticism from Hottel, Telkes convinced her boss to approve the project, leading the team to build the house on university grounds in 1946. Yet, despite the sound science behind her theory, the experiment itself proved unsuccessful in practice: the Glauber’s Salt corroded their containers until they leaked irreparably.

Hottel and the rest of the team blamed Telkes’ experiment design, while Telkes claimed that Hottel’s poor supervision of the graduate students who ran the experiment was at fault, because they had not adequately controlled the building’s temperature.

In his chronicle of MIT’s solar project and Telkes and Hottel’s professional relationship, journalist Meir Rinde suggests that clashes between Telkes and her other colleagues were not rare, “in part because of her assertive personality but also, perhaps, because of a bias against the sole woman on the team.” He quotes MIT dean George Harrison, who, when reporting on the solar fund years later, wrote that Telkes was “a person of strong opinions which she expresses forcibly, who does not submit willingly to direction” and that people — even those who didn’t directly work with her — "found it impossible to agree with her for any length of time.”

Such comments likely wouldn’t have surprised others who knew Telkes throughout her life. Andrew Nemethy, a relative who knew her when he was a child, said she was “very entertaining,” but “unsteerable away from her vision. People didn’t know what to make of her.” Joy Olgyay, Telkes’ goddaughter, also described Telkes’ peculiar manner.

Olgyay told PBS:

"Her mind was somewhere else, it was not on these everyday things. She did not cook, she did not sew. She was a visionary and thinking about projects and problems, and the other things didn’t matter."

Quotes like these mirror depictions of geniuses and visionaries throughout time — their absent-mindedness as they work on complex problems in their heads, their directness and lack of care for everyday pleasantries — behaviors that rarely raised an eyebrow when describing Telkes’ predominantly male contemporaries, and in fact are often framed affectionately as lovable, or at least acceptable, eccentricities.

In addition to highlighting her personality, Telkes’ heated disagreements with Hottel underscored her visionary nature. While Hottel, and many contemporaries who worked on or researched energy alternatives, would continue to reduce the worthiness of solar energy to a simple cost-benefit analysis — solar heating was still more expensive than heating with oil and gas — Telkes always took into account the far-reaching consequences of improving this technology. She knew it had implications beyond its benefits for the individual user, factoring in the vast network of those affected in an increasingly global economy. She envisioned a world in which workers wouldn’t need to be hurt or killed extracting materials such as coal or oil, and in which those without access to traditional sources of energy would instead have a widely available, free alternative.

The failure of the solar house experiment led to more than a disagreement of who or what was to blame. Hottel removed Telkes from her position, and she was reassigned to MIT’s Metallurgy department. Even MIT President Karl Compton’s attempt to intervene on Telkes’ behalf was insufficient to save her position on the project team. Still determined to make a working solar house, she sought out Eleanor Raymond, a renowned architect, and Amelia Peabody, a sculptor and philanthropist. At first, Peabody politely rejected Telkes’ pitch, but nature, or fate, soon intervened. A powerful New England blizzard and freezing temperatures coincided with a coal and heating oil shortage in the winter of 1947. The pain residents felt proved Telkes’ point that common fuels were not reliable to a fault. Telkes, with this little nudge from nature on her side, managed to convince Peabody to fund the project the next year, in 1948. In a letter to Telkes, Raymond celebrated the “historic” collaboration between the three women, calling it a “thrilling time” for all.

Maria Telkes (left) and architect Eleanor Raymond (right) in front of the Dover Sun House. At the time, the house was a unique collaboration between three women—Telkes, Raymond, and philanthropist Amelia Peabody—which contributed to the publicity it garnered. Raymond developed a friendship with Telkes, whom she called "a versatile lady, and an amusing one."

(Courtesy of the Frances Loeb Library. Harvard University Graduate School of Design)

The new experimental house — dubbed the Dover Sun House — was built on Peabody’s Dover, Massachusetts estate, and Telkes again heated the house with Glauber’s Salt. This time the house had inhabitants, a second cousin of Telkes and his wife, who had fled Hungary with their baby when the Soviets had invaded after the war.

The experiment appeared successful and garnered a lot of media attention. Popular Science hailed the house with the “sun furnace,” and thousands of visitors toured the home. Telkes, who had learned quite a bit about the media since her early brushes with reporters like the not-so-charming Brisbane, and others, capitalized on the opportunity.

“She was a very savvy PR woman and she may have realized it was a savvy marketing maneuver. That was part of why she selected us to live in that house,” said Andrew Nemethy, son of the couple and resident of the Dover Sun House.

Telkes jumped on this new media craze to promote other solar projects. In 1952, she developed a 200-square-foot solar distiller on the Cohasset, Massachusetts sea shore. “Raised from the sands on stilts and topped with triangular glass covering,” as one newspaper described it, “the general effect was like a combined hothouse and seaside pier.” Functioning somewhat like Telkes’ old portable solar still, this distiller could produce 44 gallons of drinking water a day. As with previous solar-powered inventions, Telkes speculated about its potential usefulness in the developing world.

“Places in South America, particularly Peru, that haven’t enough water would benefit. It doesn’t matter how dry it is. The hotter the sun, the dryer the air, the more drinking water the sun will produce,” she told a journalist.

Seemingly on cue, the journalist tried to get Telkes to talk about herself, expecting readers to be curious about the Sun Queen’s — or any woman scientist’s — private life. She quickly redirected the conversation toward her lifelong passion for science and solar energy.

Meanwhile, back at MIT, Hottel and the rest of his team at the Solar Project stewed over the enormous interest in the Dover Sun House, which Telkes had created independently after being removed from their project. In private letters, they expressed their outrage at Telkes’ refusal to “submit,” and spoke in veiled language about how the female trio’s collaboration might negatively affect the university’s image.

In the summer of 1953, Telkes was fired from MIT, a culmination of the tension that had been boiling for years.

Adding insult to injury, by 1954 — six years after its construction — the Dover Sun House experiment ultimately proved unsuccessful. The high electric bills from powering the fans that circulated heated air canceled out most of the savings on fuel, and many crucial components had failed and needed replacement. Ultimately, an oil furnace was installed in the attic for the family. Worried about how the apparent failure would affect future investment in solar energy, Telkes spent a long time attempting to set the record straight, arguing in articles that the experiment had in fact been a success. Unfortunately, what she feared did come true: solar heating came to be considered a proven failure, and for decades, architects refused to work on projects that involved it.

But failure, perceived or actual, would not be her lasting legacy.

A promotional photo of the solar oven commissioned by Maria Telkes. Telkes’ solar oven design was fairly simple. An insulated metal box is covered with glass over the area where food is placed. The sun’s heat through the glass is then amplified by four metal plates at 60-degree angles, and by mirrors between the plates.

(Courtesy of Maria Telkes Papers, Design and the Arts Special Collections, Arizona State University Library)

Moving on to NYU's College of Engineering, Telkes organized and directed a solar energy laboratory. While there, the Ford Foundation gave her a grant to design a solar oven for places with limited access to common sources of fuel or energy.

Telkes took on the challenge and laid out some requirements for her solar oven: it had to be able to cook, boil, and bake according to any local custom; it had to be cheap to make; it had to work in the early evening; and it had to be durable, portable, and simple to use and clean. She managed to come up with a device portable enough that she could carry it under her arm, but powerful enough to reach temperatures of 350 degrees without any fuel or energy source other than the sun. It could also be constructed with common materials like wood, glass, and metal plates, and cost about four dollars to make. This made it ideal for its purpose: to provide a cheap, accessible cooking method for people in developing countries.

Telkes would head NYU’s solar energy laboratory for five years. She then spent the 1960s directing solar energy research for a few private companies, including defense contractors Curtiss-Wright and Melpar. In 1972 she returned to the academic sector, accepting a job at the University of Delaware (UD)’s Institute of Energy Conversion.

While at UD, Telkes was visited by author Daniel Behrman, who was writing a book on solar energy, and his wife and photographer, Madeleine de Sinéty. By then in her early 70s, Telkes, according to Behrman, appeared younger, and dressed “with the care of a prewar European.” She wore a pendant depicting Inti, the sun deity of the Incas, whose empire had spread across western South America from 1438 to 1533. De Sinéty was impressed with Telkes, whom she described as an “adorably mad Hungarian, a genius.”

“With one hand, she started to put on lipstick because I had a camera; with the other, she reached into a steel box and pulled out […] patents on her own inventions,” De Sinéty wrote, capturing, in a way, the perfect confluence of the two roles Telkes had been playing for years, as the media-friendly spokesperson for solar energy and as the consummate scientist with the knowledge and data to back up every word she said.

After a half-century as a scientist, Telkes had firmly established herself as an innovator with more than 20 patents to her name in the U.S. alone.

In 1952 Telkes had been the first recipient of the Society of Women Engineers Achievement Award, and in 1977, she received prestigious lifetime achievement awards from the National Academy of Science and the International Solar Energy Society. The latter recognized her as one of the foremost pioneers in the field of solar energy. But as a journalist who interviewed her later that year observed, she seemed to still feel she had something to prove.

“At the first sign of a questioned look on an interviewer’s face, she dives into her desk or files to produce a document to substantiate the fact she is reciting. The questioned look is probably more related to trouble with her Hungarian accent than any doubt of the fact,” the journalist wrote about Telkes.

Toward the twilight of her career, Telkes appeared to have found more supportive collaborators, particularly at the Institute of Energy Conversion at the University of Delaware, who supported her research on electricity-generating photovoltaic cells, an experimental new solar technology of the 1970s.

In addition to her scientific prowess, Allen M. Barnett, then director of the Institute, praised Telkes’ creativity and problem-solving skills, as well as one of her more uncanny abilities in an interview with a journalist.

“She has the ability to do a simple experiment and calculate on the back of an envelope how much it will cost to produce it commercially. The government then spends millions of dollars to verify her work. I don’t think this trait is fully appreciated by her colleagues,” Barnett said.

Telkes would continue her work at the institute, which included the building of Solar One, UD’s experimental solar-powered house, until she retired in 1978. She would continue to act as a consultant for the university until her passing.

At the University of Delaware, Telkes and other collaborators finally built a successful solar house prototype, Solar One, which generated both heat and electricity from the sun. Though some credit it with starting a solar heating craze, its technology became antiquated with the advent of photovoltaic panels.

(Courtesy of Maria Telkes Papers, Design and the Arts Special Collections, Arizona State University Library)

In 1995, Telkes returned to her native Hungary for the first time in over 70 years. While there, she passed away, 10 days before her 95th birthday. Perhaps because she had been so private, choosing to focus her public efforts on the science over herself, or because Hungary didn’t know her as the famous Sun Queen, U.S. newspapers didn’t find out about and report her death until the next year.

While Telkes may have felt her work was underappreciated, one particular piece of her earlier vision carried on even after her death: solar ovens. Scientists William Lankford and Daniel Kammen, who were teaching people in remote areas of Africa and Central America how to build and use solar ovens, affirmed her observations about the difficulties faced by some inhabitants of the tropics, “with practically limitless energy directly over their heads” but “very little else than their own muscular energy in their hands,” as she had said once. In a 1990 Nature magazine article, they told the story of an indigenous Guatemalan woman who had to walk three hours a day to find wood for cooking as the forest border was pushed further away by deforestation.

The dependence on wood for cooking by millions of people worldwide has many devastating consequences. Deforestation erodes the soil and contributes to climate change. Also, sources of fuel are misspent; for example, dung that could be used as fertilizer for growing food is instead used for cooking. Moreover, families who cook over wood, coal, or dung fires, commonly in poorly ventilated homes, are more prone to retinal damage and respiratory illnesses that often result in death. Then there are the more immediate, quality of life effects:

“Hours spent gathering wood or biomass fuel robs families of time and energy needed for education and work,” wrote Lankford and another co-author, Laura Snyder Brown.

Lankford and others who have worked with him in the Central American Solar Energy Project (CASEP) since the 1990s, including Kammen and Brown, have reported great success introducing solar ovens in Central America by working with community groups in Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. They used a version of Telkes’ design since it was easier to build and use and more adaptable than other solar oven designs. Participants in their workshops thanked them for how much time the solar oven had gifted them back. Lankford and Kammen also reported that at least 80,000 solar ovens have been sold in India during the past century, thanks to a government subsidy.

“Women who use solar ovens tell us that they save the time spent on gathering firewood and the money spent on fuel; are able to leave their meals to cook unattended; and enjoy clean indoor air and improved health,” report Lankford and Brown. They also use their newly gained free time and skills learned through CASEP’s workshops to “advocate for themselves and others” and start community initiatives such as feeding programs, microloan enterprises, and urban farms.

Speaking at a conference of women scientists in 1964, called Focus on the Future, Telkes described herself as having lived “an active solar life” developing “practical devices for the basic needs of human existence.” But after decades as a pioneering woman scientist, the only woman among men in many laboratories and teams, she saw a parallel between the “untapped potential” of the sun and the “untapped potential” of women scientists, and encouraged her audience to harness both for the betterment of all.

It is most appropriate that our untapped potential should develop the untapped energy source for the greatest benefit of the least developed group of humanity. Perhaps there will be some of you who will also ‘Reach for the Sun.'

Credits

Produced by the USPTO’s Office of the Chief Communications Officer. For feedback or questions, please contact OCCOfeedback@uspto.gov.

Story by Axel Alfaro Hernandez. Additional contributions from Whitney Pandil-Eaton, Jon Abboud, Eric Atkisson, Rebekah Oakes, William Lincicome, Jake Wade, and David Kadas. Special thanks to Arizona State University.

The first photo, Maria Telkes in 1956, is courtesy of Library of Congress.

References

American Experience, “The Sun Queen,” directed by Amanda Pollak, aired April 4, 2023 on PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/sun-queen/

Arnot, Charles. 1955. “Push that solar energy button.” The Tampa Tribune (Tampa, Florida), August 7, 1995, 55. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://www.newspapers.com/image/328568156

Barber, Daniel A. “The Modern Solar House: Architecture, Energy, and the Emergence of Environmentalism, 1938–1959.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2010.

Behrman, Daniel. 1976. Solar energy: The awakening science. Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown, and Company, 1976.

“Book Starts Career.” 1965. Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), March 29, 1965, 13. (Accessed February 20, 2024). https://www.newspapers.com/image/119423522

Brisbane, Arthur. 1932. “Arthur Brisbane says (column).” The Birmingham News (Birmingham, Alabama), October 24, 1932, 4. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://www.newspapers.com/image/1001509122/

Brown, Laura S., and William Lankford. 2015. “Sustainability: Clean cooking empowers women.” Nature, May 20, 2015, 284-285. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://doi.org/10.1038/521284a

Butler, Kirstin. 2023. “The marvelously inventive life of Mária Telkes.” PBS American Experience, March 17, 2023. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/sun-queen-marvelously-inventive-life-maria-telkes/

Encyclopedia.com. Telkes, Maria. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/telkes-maria

"First International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists (program)." (Accessed February 20, 2024). https://uihistories.library.illinois.edu

Judd, Wallace C., Jr. 1977. “Institute scientist able to store sun’s energy.” The Morning News (Wilmington, Delaware), September 11, 1977, 49. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://www.newspapers.com/image/158285375/

Kammen, Daniel, William F. Lankford. 1990. “Cooking in the sunshine.” Nature, November 29, 1990, 385-386. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://doi.org/10.1038/348385a0

Kidder, Tracy. 1977. “Tinkering with sunshine.” The Atlantic Monthly, October 1977, 70-83. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://www.proquest.com/magazines/tinkering-with-sunshine/docview/204085323/se-2

Lankford, William F. 1990. “Making a Difference with Solar Ovens.” EPA journal, July-August 1990, 47-79. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://www.proquest.com/docview/15015643

Nemethy, Andrew. 2019. “Solar power meets girl power.” The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts), March 24, 2019, Z21-Z24. (Accessed March 19, 2024.) https://www.newspapers.com/image/546606849/

Prim, Mary. 1952. “Woman scientist harnesses the sun.” The Decatur Daily (Decatur, Alabama), March 13, 1952, 16. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://www.newspapers.com/image/534877600/

Raymond, Eleanor. 1948. Letter to Amelia Peabody, May 21, 1948, Maria Telkes collection, Box 79, Folder 1. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona State University: Design and the Arts Special Collections. http://azarchivesonline.org/

Rinde, Meir. 2023. “The Sun Queen and the Skeptic: Building the world’s first solar houses.” Science History Institute, May 19, 2023. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/the-sun-queen-and-the-skeptic-building-the-worlds-first-solar-houses/

Saxon, Wolfgang. 1996. “Maria Telkes, 95, an innovator of varied uses for solar power.” New York Times, August 13, 1996. (Accessed February 26, 2024.) https://www.nytimes.com/1996/08/13/us/maria-telkes-95-an-innovator-of-varied-uses-for-solar-power.html

“Strange stove cooks food with sun’s heat.” 1955. Lansing State Journal (Lansing, Michigan), June 4, 1955, 34. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://www.newspapers.com/image/207506920/

Thone, Frank. 1931. “Unusual life-like behavior of Dr. Crile’s man-made cells.” Abilene Daily Reporter (Abilene, Texas), March 12, 1931, 13. (Accessed February 22, 2024.) https://www.newspapers.com/image/760383708

Tuthill, Mary. 1980. “Lessons of Leadership: Louis Cabot: He made room at the top.” Nation's Business, December 1980, 42. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://www.proquest.com/docview/231703784

Tyson, Peter. 1994. “Solar ovens heat up in the tropics.” Technology Review, May-June 1994, 16. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://www.proquest.com/magazines/solar-ovens-heat-up-tropics/docview/195334005/se-2

Vamos, Eva. “Mária de Telkes (1900–1995)”. European Women in Chemistry. Ed. Jan Apotheker and Livia Simon Sarkadi. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag & Co. KGaA, 2008. (Accessed February 20, 2024.) https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527636457.ch32