Perseverance, thy name is Bette

Single mother Bette Nesmith Graham struggled to financially support her son on her meager secretarial salary while trying to overcome a technological learning curve that could very well have cost Nesmith Graham her job. Through ingenuity and perseverance, this high school dropout became a business magnate who transformed the office supply industry in the 20th century.

11 min read

Each month, our Journeys of Innovation series tells the stories of inventors or entrepreneurs who have made a positive difference in the world. This month, Whitney Pandil-Eaton's story focuses on Bette Nesmith Graham, who transformed the office supply industry of the 20th century with her trade secret correction fluid called Liquid Paper.

Do you know an innovator or entrepreneur with an interesting story?

Watching artists paint the windows of this Texas Bank and Trust building in downtown Dallas, Texas- photographed here in the 1950s- inspired Bette Nesmith Graham to create a corrective fluid that would revolutionize the office supply industry of the 20th century.

(Courtesy of the University of Texas at Arlington)

She stood outside the Texas Bank and Trust high-rise building in downtown Dallas one mild southern winter day, watching brush stroke after brush stroke as the artists slowly transformed the bank’s exterior windows into a painted festive scene for the upcoming Christmas holidays. Mesmerized, she observed the artists layer different colors of paint on the windows, erasing misplaced brush strokes in an instant.

Then it clicked.

Her lifelong passion for the arts — combined with a healthy dose of perseverance — would save her career.

Perseverance had served Bette Clair McMurray well. She used it to pursue her GED after dropping out of school at age 17 to attend secretarial school and marry her high school sweetheart, Warren Nesmith. It was perseverance’s cousin, grit, that helped her raise their infant son, Michael, while Nesmith served overseas as a soldier in World War II. Now, creative determination would save her job.

The clack, clack, clack sound of typewriters was ubiquitous in offices during the 1950s.

During this time many offices transitioned from manual typewriters to electric typewriters. While electric typewriters helped to automate many processes increasing efficiency, the messy carbon-film ribbons and sensitive key triggers resulted in more typos. An eraser could be used to fix the mistake, but the carbon ink would smear all over the page, necessitating the remaking of the document for a single error.

In her more than 10 years as a secretary, Bette Nesmith Graham had propelled herself to a high professional level, serving as the executive secretary for the chairman of the Texas Bank and Trust.

Although highly skilled overall, her typing proficiency was subpar, a fact made worse by the transition from manual to electric typewriters. She made frequent errors, for which she tried a variety of ways to fix in order to avoid having to redo a document completely. As a single mother — Bette and Warren divorced in 1946 — she couldn’t afford to lose the primary means of support for herself and her son. She had to find a way.

“I didn’t have a fellow at the time so I had to do it by myself,” Nesmith Graham said in an interview later in life. “I had to appreciate that as a woman I was strong, complete, adequate.”

A display of Liquid Paper products and accessories located at the Women’s Museum in Dallas, Texas.

Recalling her observation of the bank window painters, one day Nesmith Graham brought a small jar of white, water-based tempura paint into the office and began using it to cover up typos with a watercolor brush. It worked so well, it is said, her employers seldom noticed. Nesmith Graham quietly used her liquid creation for a time until other secretaries in the office took notice and flooded her with requests for their own bottles of the wonder fluid.

“Everybody was enthusiastic about it,” she recalled in a company newsletter. “But I was still thinking about it mostly for my own use until an office supply dealer asked me one day: ‘why don’t you market that?’”

Encouraged by the positive response, Nesmith Graham took on a second job, working nights at her north Dallas home filling orders for other secretaries in the area. During that time, she worked alongside her son’s chemistry teacher and an industrial polymer chemist to perfect the formula for what would initially be called “Mistake Out.”

“I wanted the product to be absolutely perfect before I distributed it, and it seemed to take so long for that to happen,” Nesmith Graham said in a 1979 interview with Texas Woman magazine about the years spent experimenting with different formulas.

Despite the increasing demand for her correcting fluid, her secretarial salary of $300 per month meant Nesmith Graham was unable to afford the $400 patent application fee in 1956.

Living paycheck to paycheck despite doing occasional side jobs involving art and modeling, Nesmith Graham’s son Michael recalled in an interview that his mother would frequently “burst into tears of panic.” She recalled in a company newsletter about her struggles to support her son, wondering where she would get money for their next meal.

“I was struggling against mediocrity,” Nesmith Graham said. “I felt that I was special, that I had something special to give. But I didn’t know what that was going to be.”

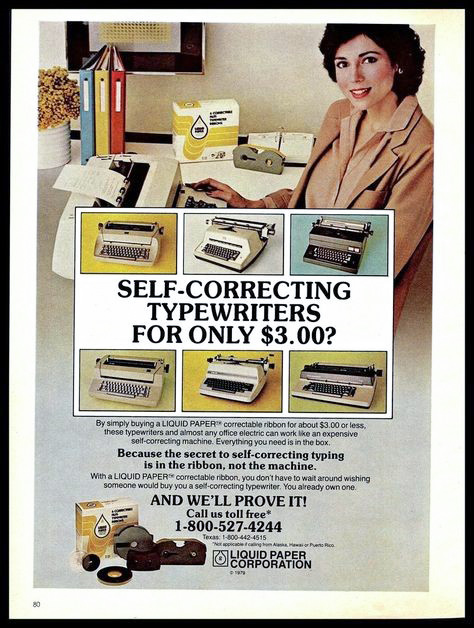

Creator of electric typewriters, IBM declined to market Bette Nesmith Graham's correction fluid when she approached the company in 1957, but would then place one of the first bulk orders for Liquid Paper.

She continued her secretarial duties by day while at night she wrote to potential buyers and sent out samples- even traveling from Dallas to San Antonio and Houston to showcase her creation.

In 1957, in an attempt to convince IBM to market her product, Nesmith Graham sent the company’s advertising agency two typed documents – one with errors corrected with an eraser and the other using her newly renamed Liquid Paper secret correcting formula – along with a personal note that said, “I truly believe that this can mean a turning point from the old methods – a new era.”

IBM declined. She was on her own, again.

“I felt very inadequate. I didn’t know how I was going to do it,” she said. “The problems seemed insurmountable, but I saw this challenge that I was to meet.”

Orders continued to increase to the point that Nesmith Graham was able to hire her son and his friends for $1 per hour to fill nail polish bottles with the correction fluid and cut the tips of the mini brushes inside the cap at an angle.

But progress on one end would cost her on the other.

The tightrope walking between her two jobs ended abruptly when Nesmith Graham accidentally signed a letter with “The Mistake Out Company” on the bank’s stationary while performing her secretarial duties. She was promptly fired.

Having lost her primary means of financial support, she thrust herself into commercializing her whiteout liquid.

“Persistence is like courage,” Nesmith Graham said. “Either you have it or you don’t. But it is the willingness to have it, the wanting to have it that makes it possible. You have to want it more than anything else.”

With the help of a small group of employees, Nesmith Graham began selling Liquid Paper to area office supply stores.

In 1958, Fortune 500 behemoth General Electric placed the largest first single order — 400 bottles in three colors — after The Secretary trade magazine mentioned the company, calling Liquid Paper “the answer to a secretary’s prayers.” Orders from other large businesses, like the formerly reluctant IBM, soon followed.

Despite its initial success, The Mistake Out Company, like many companies, struggled to become profitable in the early years. This would change after Nesmith met and married her second husband, Robert Graham, in 1962. A former frozen food salesman, Graham used his experience to sell Liquid Paper to office supply stores across the country. As orders steadily increased, The Mistake Out Company’s operations moved from Nesmith Graham’s kitchen to her garage, then to a trailer, and subsequently a four-room house. With Graham’s sales experience and influence as an executive, the company was able to become profitable in 1964. That year, what had started as a scrappy business selling 500 bottles per week had grown ten-fold and was meeting demand for more than 5,000 bottles per week.

Years of dogged determination had finally paid off.

By 1968 the company was a million-dollar business that produced 1 million bottles a year. That same year, Nesmith Graham renamed the company Liquid Paper Corporation and received a trademark. Her correcting liquid formula — which took more than a decade to perfect — became a trade secret.

Like Coca-Cola or Kentucky Fried Chicken, Nesmith Graham’s trade secret helped her beat the competition.

In 1968, Liquid Paper faced just three other companies in the correction fluid market. By 1979 that number increased to 30. Despite the competition, the company was able to increase its market share from 30 percent in 1971 to 75 percent in 1979. This was due to the superiority of Nesmith Graham’s trade secret formula according to a financial court filing. At its peak, Liquid Paper was producing 25 million bottles a year in factories located in Dallas and internationally in Toronto, Canada, and Brussels, Belgium. The product was exported to 31 countries.

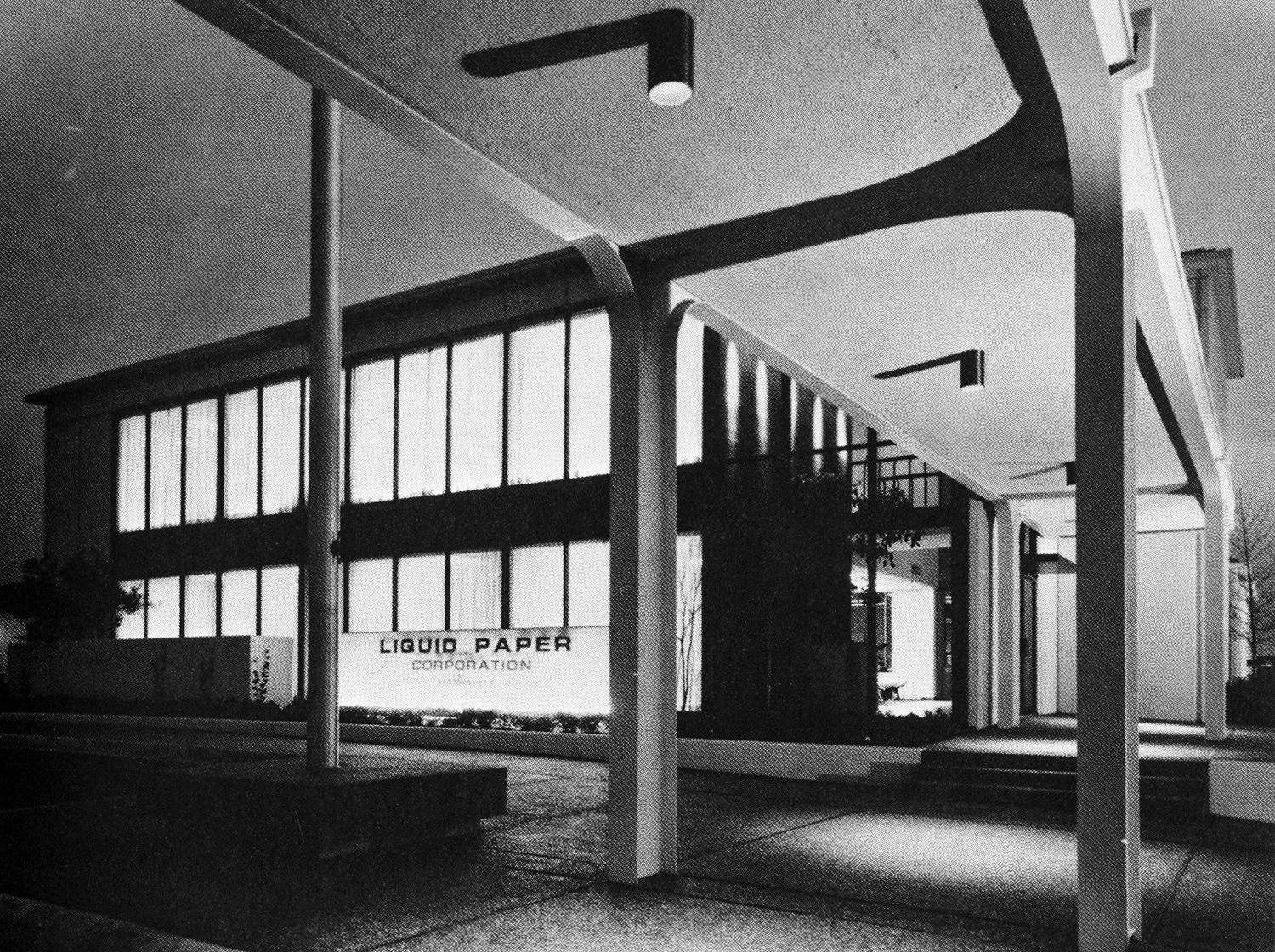

Liquid Paper Corporation headquarters, built in 1969, included facilities that were ahead of its time such as an in-plant library, on-site childcare center and wheelchair-accessible areas. Deeply religious, founder Bette Nesmith Graham also adopted progressive workplace policies.

(Courtesy of University of North Texas Special Collections)

Deeply religious, Nesmith Graham incorporated Christian philosophies and the lessons learned as a single parent into her growing company.

Liquid Paper Corporation’s 11,000 square foot headquarters, built in 1969, was ahead of its time and some important U.S. legislation. It included an in-plant library, on-site childcare center, an employee-owned credit union, and wheelchair-accessible facilities 21 years before the Americans with Disabilities Act. She also adopted progressive workplace policies and offered tuition reimbursement to employees.

“The premise of the company was to create an environment in which people could grow,” explained Rob Erwin, president of Liquid Paper in 1979.

Outside of the company, Nesmith Graham used her growing wealth to establish two foundations, the Bette Clair McMurray Foundation in 1976 and the Gihon Foundation in 1978, which supported women’s welfare, business efforts, and the arts.

“The true value in business is never in the dollar, but in the benefit that it brings to humankind,” she said. “Money does not solve problems. Money is a tool.”

While the company was prospering, Nesmith Graham’s second marriage deteriorated and ended in 1975. Following the divorce, her ex-husband – then chairman of the board – convinced a group of executives to bar Nesmith Graham from the premises. He then went about trying to change the Liquid Paper formula that would remove trade secret protections and strip Nesmith Graham of the income from her royalty rights.

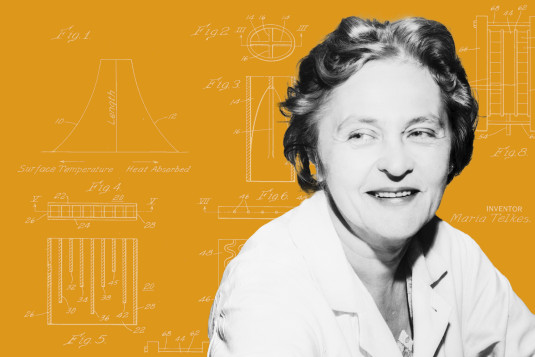

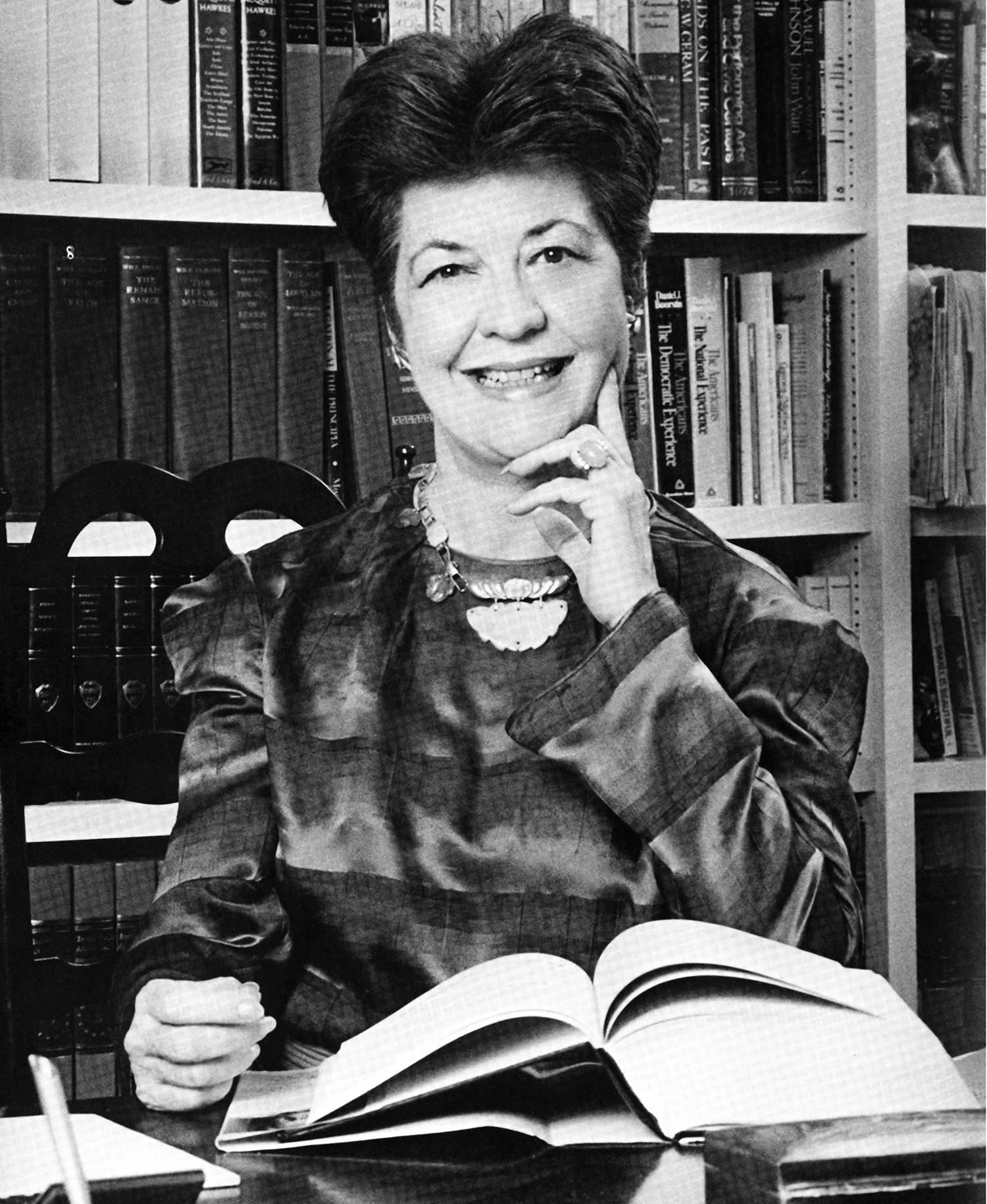

Bette Nesmith Graham, inventor of Liquid Paper.

(Courtesy of University of North Texas Special Collections)

She was down, but not out.

Despite failing health, Nesmith Graham wrestled back control of the company by maintaining a 49 percent stake in Liquid Paper until she was able to sell the company to the Gillette Corporation for $47.5 million in 1980.

Shortly after that, she reminisced about her journey from high school dropout to business magnate in an oral history interview with officials at the University of North Texas.

“I find it’s such a marvelous period when you’ve been patient and stood your ground and one day you see that growth has been going on around you all the time,” Nesmith Graham said. “It’s like a plant that is rooted in the ground. For a long time, you don’t see much happening, but all the time the plant is developing a stronger root system that reaches out to farther places.”

Less than six months after selling the company Nesmith Graham died, leaving half of her fortune to her charities and the other half to her only child, Michael Nesmith, who cemented his own place in history as a singer and songwriter in the American pop rock band, The Monkees.

From high school dropout to business magnate, Nesmith Graham’s legacy is one of perseverance and irony. The typo that cost her her secretarial job would be a problem she would fix for millions of other workers, transforming the office supply industry in the 20th century.

Credits

Produced by the USPTO’s Office of the Chief Communications Officer. For feedback or questions, please contact inventorstories@uspto.gov.

Story by Whitney Pandil-Eaton. Additional contributions from Lauren Ingram. Special thanks to the library staff of the University of North Texas Special Collections.

References

Liquid Paper Corporation. "Letter Perfect." November 1979-June 1980. Liquid Paper Corporation Records. University of North Texas Special Collections.

Liquid Paper Corp. v. United States, 2 Cl. Ct. 284 (1983) | Caselaw Access Project

Lemelson-MIT staff. 2023. “Bette Graham Liquid Paper.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Bette Graham | Lemelson (mit.edu)

Jones, Nancy. November 23, 2020. “Graham, Bette Clair McMurray.” Texas State Historical Association. TSHA | Graham, Bette Clair McMurray (tshaonline.org)

Vare, A., and Ptacek, Greg. January 31, 1988. “Mothers of invention.” Chicago Tribune. Page 73, 78.

Chow, Andrew. July 11, 2018. “Overlooked No More: Bette Nesmith Graham, Who Invented Liquid Paper.” The New York Times. Overlooked No More: Bette Nesmith Graham, Who Invented Liquid Paper - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Crockett, Zachary. April 23, 2021. “The Secretary who turned Liquid Paper into a multimillion-dollar business.” The Hustle. The secretary who turned Liquid Paper into a multimillion-dollar business - The Hustle