"There's a better way of doing that"

With 49 patents, Beulah Louise Henry was one of the most prolific inventors of the 20th century. Her typewriters, toys, sewing machines, and women’s apparel made Henry a famous and beloved figure across the country.

16 min read

Each month, our Journeys of Innovation series tells the stories of inventors or entrepreneurs who have made a positive difference in the world. This month’s story focuses on Beulah Louise Henry, the most prolific female inventor of the first half of the 20th century.

It’s Jazz-Age New York City, and Beulah Louise Henry is rushing around Madison Square. She has paper but needs a pencil quickly, before her new idea for a silent typewriter slips away. It has come to her just now, on her way uptown from a meeting in the front office of a machine shop, where the clack-clack-clack of typewriters distracted and then inspired her.

She gets her pencil, finally, from the third stranger she’s asked, and sets about sketching. Next will come a makeshift prototype, another series of sketches, and then appointments with professional model makers and draftsmen. Henry is a professional inventor, after all, and knows a thing or two about getting a patent and capitalizing on her creativity. She is on her way to becoming the era’s most prolific female patentee.

New York City’s Madison Square, ca. 1925, where Beulah Louise Henry sketched the first of her many patented improvements in typewriter technology. (Museum of the City of New York, X2011.34.121)

By the end of her career in the 1960s, Henry, in her 80s, had 48 patents and national fame. (The 49th patent came posthumously in 1970.) Her patented technologies were complex and ingenious, yet easy to manufacture and even easier to use. Many of her inventions—toys, apparel, appliances, and office equipment, especially—appealed to America’s burgeoning middle classes and brought Henry financial rewards. The press took note of these successes and ran countless interviews and articles about her unique process and uncommon versatility.

Henry had been inventing since her childhood in Charlotte, North Carolina, she told interviewers, and had enjoyed the support of her parents, Walter Henry, a lawyer and orator, and Beulah Holden, a homemaker and member of North Carolina’s political elite. Their daughter’s first idea for an invention came around 1893, when she was 6 years old and visiting her grandmother’s home in Raleigh. Noticing that the hem of the flag sometimes brushed the ground as it was being lowered from the pole of the neighborhood post office, Beulah Louise said to her family, “There should be a hole right through that pole so the flag could drop through and never touch the ground.”

A few years later, Henry, aged 9, created her first prototype, this time for a belt with a paper holder attached, after she had seen a man struggle to read the news and carry his groceries at the same time. Like her later inventions, Henry’s earliest prototypes were the products of observation and problem solving.

According to press reports from later in her life, Henry finished high school and attended one or two of North Carolina’s women’s colleges in the 1900s. In the 1910s, she moved with her parents to Memphis, Tennessee. Single and increasingly independent, Henry nonetheless remained devoted to her family for the rest of their lives together.

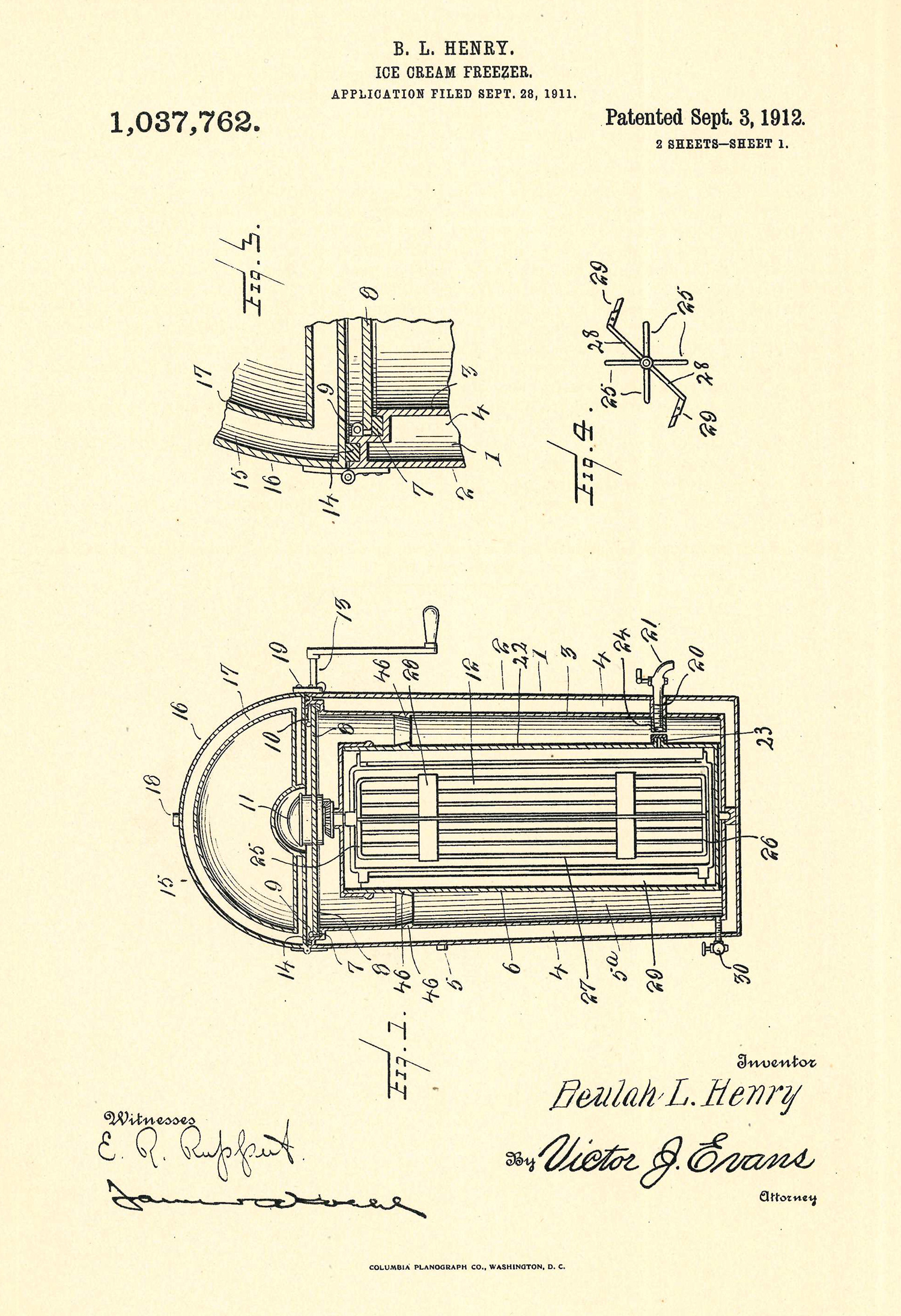

With her parents’ support, Henry received her first patent (no. 1,037,762) in 1912. The device, an ice-cream maker, could work with minimal use of ice, a commodity in short supply in this era before freezers. Operated either by hand or by motor, depending on the availability of electricity (then still a novelty), the apparatus doubled as a water cooler. This first patent reflected all the hallmarks of a Beulah Louise Henry invention: versatility, efficiency, economy, and ease of use—qualities that would make her prototypes stand out to manufacturers and retailers in the next several decades.

Beulah Louise Henry received her first patent in 1912, for an ice-cream maker that doubled as a watercooler. (Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

Yet commercial success did not arrive right away. There is no record of the ice-cream maker having made Henry any money, and her second invention, a parasol with interchangeable, snap-on covers to match a woman’s outfit, seemed to be going the same way. Manufacturers and retailers in Memphis, where the family was living at the time, weren’t interested.

Around 1920, Henry’s parents agreed to relocate to New York City with their daughter to give her the best possible chance of making it as an inventor. Once there, Henry “made endless excursions to the offices of umbrella manufacturers, and tiresome trips up flights of dingy stairs to the workshops of various model makers,” trying to convince a male-dominated industry of her idea’s potential. She recalled, “Everyone said it wouldn’t work, piercing steel ribs with the snaps necessary to hold the covers in place. Even the model makers refused to try.”

So Henry made her own model. When she returned to the model maker with her creation in hand, “the man admitted that the thing could be done. He even said that he would like to make the models. I knew then that I had won!”

With the patent, the prototype, and persistence, Henry’s parasol soon turned into a commercial reality and success. New York City became her permanent residence, mid-priced hotels her preferred style of accommodation. A convenient and common choice for many upper-middle-class New Yorkers, the large hotels of Midtown offered Henry quick access to model makers, patent attorneys, and retailers, all the connections she would need to establish herself as a professional inventor.

A New Yorker now, Henry’s pace of innovation picked up. In 1924 and 1925, she patented improvements to the parasol (nos. 1,492,725 and 1,593,494). Then she focused on a new area of research, one that would help make her famous: children’s toys.

Henry’s first successful patent application for a toy-related technology came toward the end of 1925, for an internal structure of springs designed to make the limbs of stuffed animals spring back into position after a child had playfully bent them into different poses (no. 1,551,250). The toy “may be washed when the occasion necessitates,” according to the patent specification, and the “outer character of the doll can be quickly changed at the will of the manufacturer.” The core structure of springs was available for use in any type of stuffed figure. Again, with the promise of versatility, Henry anticipated the needs and wants of manufacturers and consumers.

She was able to license most of her next several toy-related patents: a spinning top to replace dice used in board games (no. 1,575,264), a doll that doubled as a radio set (no. 1,565,145), a waterborne chariot buoyed by inflatable swans (no. 1,639,607), and various covers and sealing devices for air-filled sports balls (nos. 1,634,146, 1,723,482, 1,723,855, and 1,769,259).

With no children of her own, Henry drew inspiration from New York playgrounds and childhood memories. As a little girl in the 1890s, she had experienced firsthand the advent of the world’s first mass market for toys, a result of the industrial revolution and the growth of the middle classes. Making up the majority in this new market, middle-class Americans let their concerns and preferences be known. More and more, they wanted toys that would contribute to the child’s moral and practical education. Manufacturers and retailers responded by selling playthings that prepared children for their adult lives. Given the ideals of the day, toymakers began to gender their wares more starkly than ever before. Toy trains and early science kits went to the boys, whereas dolls, miniature kitchen and laundry sets, and sewing machines went to the girls. Henry focused mostly on the so-called feminine side of the divide throughout her career.

In other ways, however, Henry bucked the trends. The soft, pastel hues of toys that contained her patented technologies belied the mechanical complexity within. A stuffed animal hid a structure of springs and joints. A face with movable eyes veiled an apparatus of wires and hinges. A realistic and inanimate baby doll was actually a compact, fully functional radio. On the outside, these toys fit the gender norms of the day and would have allowed girls to practice the care tasks associated with motherhood. But on the inside, Henry’s playthings were masterpieces of engineering, otherwise still the purview of men.

Her next area of innovation, typewriter technology, confirmed Henry’s tendency toward the technical. As complex machines, typewriters had been designed and improved upon by men, who enjoyed exclusive access to America’s engineering schools. As useful office equipment, however, typewriters were mostly used by women. “Typist” was one of the few white-collar occupations open to them at the time.

Henry’s first typewriter-related invention had to do with duplicates. With photocopiers not yet available, a typist’s standard option for making copies was to use carbon paper as she typed, producing one original document and a few facsimiles in gray. The carbon paper was messy, leaving black smudges on the typist’s hands, which easily traveled to her face and clothes. “Couldn’t this be corrected?” Henry asked herself. The answer turned out to be yes, with a special attachment that would slip an inked ribbon between pages without the typist having to sully her hands at all (U.S. Patent No. 1,874,749).

The women in this 1917 advertisement (left) and 1910s photograph of a New York office (right) still had to contend with messy carbon paper when it came to typing duplicates. Beulah Louise Henry solved this problem by patenting several duplicating attachments to typewriters between 1932 and 1959. (Collection of the Library of Congress)

Henry faced a significant design challenge. The attachment had to be compatible with hundreds of typewriter models if it was going to be marketable, and it had to work with the paper and ink ribbons already on hand in most offices. The device also needed to cooperate seamlessly with the typewriter itself, a notoriously finnicky machine. Henry pulled it all off and added another success to her record.

Tireless and driven, Henry could work on several inventions at once. Even as she patented the typewriter attachment and improvements on it, she attended to her earlier areas of research: parasols, just before they went out of fashion in the late 1920s, and other accessories for women. A woman of fashion herself, Henry’s activities and appearance soon got the attention of reporters.

Interviewers clamored for quotes from Henry about the secret to her success. “[I] just look at something,” she answered, “and think, ‘There’s a better way of doing that,’ and the idea comes to me.” As news spread that an amateur inventor from New York City was shattering previous records held by female patentees, glossy magazines took notice and began to publish staged photographs of Henry seated with products that incorporated her intellectual property. Editors usually chose baby dolls and often positioned them in lifelike poses on Henry’s lap, presenting the reader with the traditional equation of motherhood and womanhood.

As in this 1927 photograph, Beulah Louise Henry often posed for pictures with a baby doll incorporating one or more of her patented technologies. (Collection of the Library of Congress)

Yet these images concealed more than they revealed about Henry. Single and financially independent, she was one of society’s so-called “New Women,” a female archetype originating in the 1890s and increasing in prominence after World War I. The New Woman was urban, independent, and self-sufficient, with bobbed hair and a white-collar job. She worked into the evening, danced into the night, and gave little care to the preoccupations of her mother’s era, when a middle-class woman’s ideal place had been in the home and largely out of sight.

In most cases, the New Woman was more fantasy than reality in the 1920s, when men still dominated American politics, industry, and culture, but Henry was the real thing: a well-known inventor in the big city who could make a living on licensing her patents, the fruits of her exceptional creativity.

The profits from this and all her inventions Henry reinvested into her process, paying model makers, draftsmen, and attorneys to help prepare the next patent application while several were still pending. For the 1920s and 30s, Henry and her team averaged more than two patents a year.

This volume of activity led reporters to dub Henry the "Lady Edison” after the world-famous visionary Thomas A. Edison, who had run an innovation laboratory in New Jersey that amounted to something like a factory for patents. There, teams of inventors shared the profits and the credit with Edison, a markedly different arrangement from Henry’s.

In reality, the “Lady Edison” worked less like Edison, a manufacturer and supervisor of many, and more like the owner of a modern startup, outsourcing overhead and hustling for business all over town.

Business suffered in the 1930s, during the Great Depression, yet Henry persisted and even increased her rate of patenting. She redoubled her efforts to improve the playthings available to American children, patenting a mechanism that moved a doll’s eyes and eyelids according to the position of the arms (no. 2,022,286).

Toy manufacturers licensed the technology from Beulah Louise Henry’s 1935 patent for a “movable eye structure for figure toys” and produced thousands of lifelike dolls whose eyes could be controlled by repositioning the arms.

Then, in 1936, Henry entered yet another area of inquiry: sewing machine technology. She told reporters that an idea had come to her as she was admiring the chain-link ornamentation around the marquee of a theater outside her window. Inspired, she took to her trusty hairpins, spools, and wires to invent the single greatest improvement on the sewing machine since the introduction of electricity.

Beulah Louise Henry’s sewing machine patents affected the working lives of women disproportionately, since women were overrepresented in the sewing trades. This 1936 photograph of workers at a doll factory in Massachusetts attests to the gendered division of work in Henry’s day. (Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, 69-RP-56)

Before Henry’s contribution, a seamstress, tailor, or other textile worker had needed to stop sewing periodically, open the machine, and remove and wind thread around the bobbin, a reel under the needle plate. These frequent stoppages reduced productivity. With U.S. Patent No. 2,230,896, Henry offered a way out, a bobbinless sewing machine most suitable to people working at high volume. It had the added benefit of producing stronger seams with thinner thread, since the improvement resulted in double chain stitches “more thoroughly locked together,” according to the patent. Improvements and more sewing machine patents followed.

At the end of the 1930s, Henry went back to dolls, refining the eye structure she had already patented and then turning to other ways of making these classic toys more lifelike. With U.S. Patent Nos. 2,259,467, 2,302,318, and 2,346,580, a new voice box hidden inside the doll could produce sounds, even decipherable ones like ma-ma and da-da. In November 1941, she provided for a moving mouth and filed an application to patent a “movable lip for toy figures and means for actuating the same,” a technology that eventually found use in a novelty mannequin at Macy’s department store (no. 2,324,774).

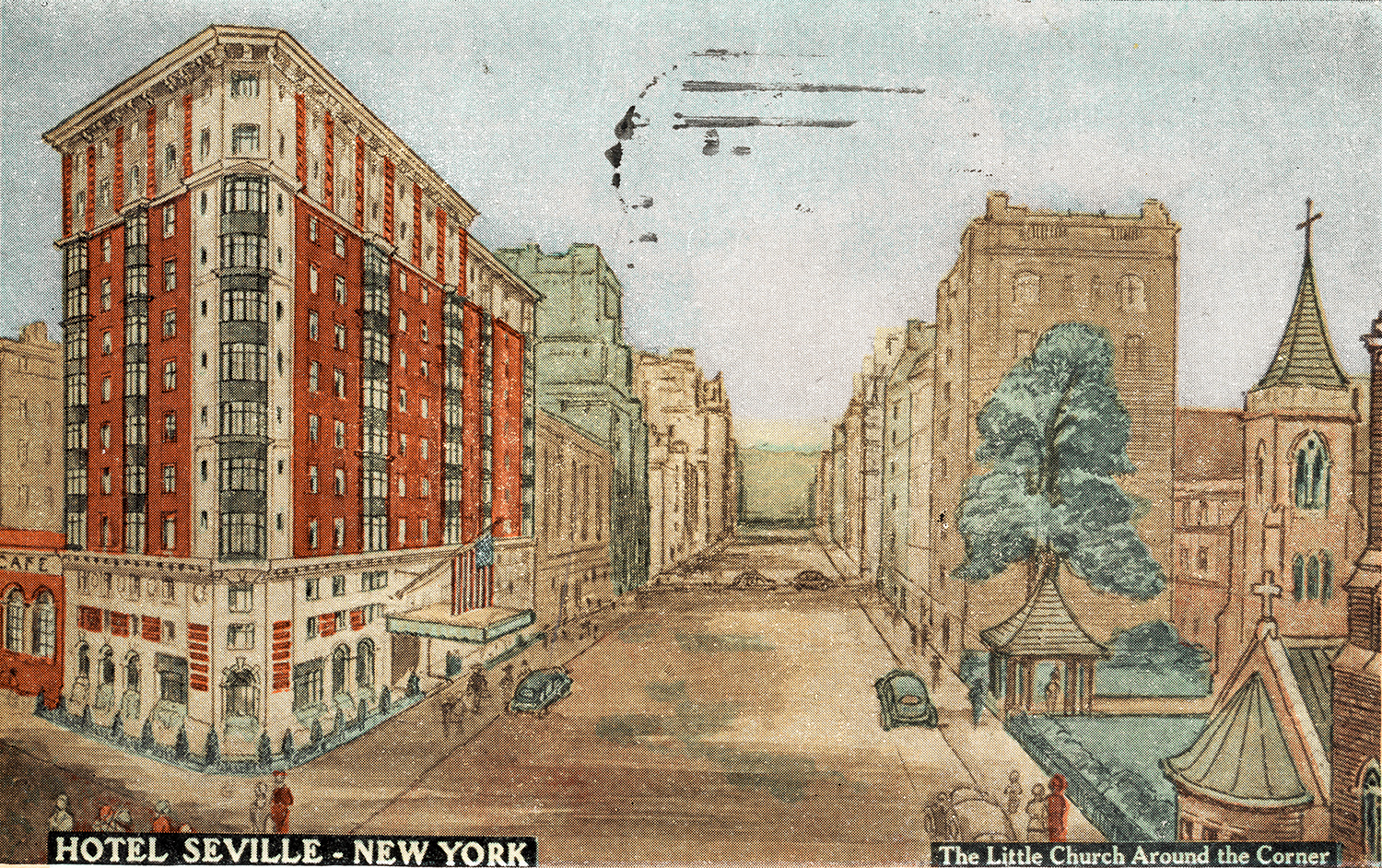

Henry’s fame was now reaching new heights. Her name appeared in papers with even greater frequency than before. Reporters especially celebrated her originality. After decades in New York, Henry still maintained a delightful southern drawl, which one interviewer actually reproduced phonetically. Her permed hair and stylish makeup made good subject matter for the photographers. Proper and put-together, Henry nonetheless let her eccentricity shine through. Her suite of rooms at the Hotel Seville, where she took up residence around 1940, hosted a succession of pets: turtles, a parakeet, a tropical oriole, two doves, several cockatiels, and a cat name Chickadee.

The Hotel Seville at 29th Street and Madison Avenue, New York City, shown here on a promotional postcard from around 1945, when Beulah Louise Henry was resident there. (Lumitone Press Photoprint, courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York, F2011.33.242)

Outside the hotel, Henry regularly accepted public speaking engagements and charmed audiences with her candor and spontaneity. At one of these events, while demonstrating her patented parasol technology, she suddenly stopped talking. The audience watched as Henry eventually glanced down and absorbed herself in rapid sketching with pad and pencil. When she finally spoke again, it was to say that she had just solved a problem in the design of a mechanism for a children’s game she was trying to perfect. These moments, recounted in the newspapers, humanized Henry and presented her as an inventor-genius with the tendency toward spontaneity and eccentricity, a description usually reserved for men like Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, Henry's male contemporaries in the science and technology fields.

In December 1941, at the apex of her career, Henry put everything on hold. The United States had entered World War II, so she joined the effort by working at a machine shop. The next patent application would not come until several months after the end of hostilities in 1945.

In her postwar patents for toys, typewriter attachments and accessories, sewing technologies, and kitchen tools and appliances, a pattern emerges that suggests Henry’s increasing technical prowess. Over time, the patent specifications and illustrations show machines of greater complexity and ingenuity. A 1950 patent offered an inflatable inner chamber with sealing mechanism to make dolls lighter and easier to clean (no. 2,503,948). Thousands of toys with this technology were sold in the 1950s . Meanwhile, Henry patented a toy cow that dispensed real milk (no. 2,577,849) and a toy dog that ingested real food (no. 2,631,408).

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office issued a collectible card in Beulah Louise Henry’s honor in 2014.

From her first, relatively simple patented devices of the early 1900s (the parasol cover and the ice-cream maker), Henry had progressed steadily over the decades to highly sophisticated technical designs that signaled her arrival as an inventive mind on par with the very best. She gave her last high-profile interview in January 1962, to the New York Times. Modest to a fault, and speaking about her reputation as “Lady Edison,” she told the reporter, “I really don’t deserve that title, but a newspaper gave it to me years ago and it has stuck.”

Journalists liked to call attention to Henry’s modesty, charm, and femininity, a standard way of framing female accomplishment through much of the 20th century. With repeated emphasis on Henry’s softer side, interviewers and even Henry herself crafted a public persona that fit the gendered stereotypes of the day. Today, we would frame her differently, not as the “Lady Edison,” a female version of a famous male inventor, but as the visionary she was, a leader in all her areas of innovation.

Henry was ambitious, prolific, and successful in her own right. Our modern homes and workplaces reflect her ingenuity. Interactive and easily cleaned children’s toys, user-friendly and increasingly efficient office equipment, and practical, easily modified fashion accessories—all echo Henry’s pioneering innovations. She also proved that with some luck, a supportive family, a creative mind, and a good business sense, one lone inventor might just make it big.

Credits

Produced by the USPTO’s Office of the Chief Communications Officer. For feedback or questions, please contact inventorstories@uspto.gov.

Story by Adam Bisno and Rebekah Oakes. Special thanks to Brooke McLane-Higginson, Robert Beebe, Amy McKune, Mike Queen, Lauren Murphree, and Tal Nadan.

The photograph at the beginning of this story shows Beulah Louise Henry in 1931 with one of her patented duplicating attachments for typewriters. (Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

References

Brooklyn Daily Eagle: Margaret Mara, “Milka-Moo’s Inventor Doesn’t Bother With Any Old Blueprints” (August 3, 1948).

Casey, Susan Mary, Women Invent: Two Centuries of Discoveries That Have Shaped Our World (Chicago: Chicago Review, 1997).

Chudacoff, Howard P., Children at Play: An American History (New York: New York University Press, 2007).

Evening Star (Washington, DC): “‘Lady Edison’ Patents Her 45th Invention” (March 9, 1962); “Models of Devices Invented by Women to Be Exhibited (September 5, 1931).

Formanek-Brunell, Miriam, Made to Play House: Dolls and the Commercialization of American Girlhood, 1830-1930 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993).

Goldin, Claudia, Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

Groth, Paul, Living Downton: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 5-10.

MacDougall, Sarah, “Beulah Henry Has Patented Thirty-Three Novelties,” in American Magazine, vol. 99, January, 1925, Through June, 1925 (New York: Crowell, 1925), 75-76.

Marovitch, Lisa, “‘Let Her Have Brains Too’: Commercial Networks, Public Relations, and the Business of Invention,” Business and Economic History 27 (1998), 140-61.

Maryland Independent (La Plata): “Miss Beulah Henry” (June 27, 1924).

McFayden, A.D., “Beulah Louise Henry,” Journal of the Patent Office Society 19, no. 8 (1937), 606-8.

McGaw, Judith, “Inventors and Other Great Women: Toward a Feminist History of Technological Luminaries,” Technology and Culture 38, no. 1 (1997), 214-31.

Montgomery County Sentinel (Rockville, MD): “High Praise Coming to Mothers of Invention” (January 29, 1932).

New York Times: Elizabeth M. Fowler, “Beulah Louise Henry Has Been Called ‘Lady Edison’” (January 27, 1962); Stacy V. Jones, “A Single Unit Serves for Mailing and Also Returning” (January 26, 1962); “New Incorporations” (March 28 and July 1, 1921).

Ratcliff, J.D., “She Invents ‘Em,” This Week Magazine (October 24, 1940), 8.

Reed, Mary Gray, “Radio Rose: This Dolly Totes a 3-Tube Receiver and Loud Speaker,” The Wireless Age: An Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Radio Communication 12, no. 9 (June 1925), 37-38 and 42.

Richmond Palladium and Sun-Telegram (Indiana): “‘Lady Edison’ Invents Umbrella with a Quick Detachable Cover” (August 30, 1921).

Stanley, Autumn, Mothers and Daughters of Invention: Notes for a Revised History of Technology (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1995), 96, 103, 403, 441, 459, 462-65.

Sunday Star (Washington, DC): “All Inventors are Not Male” (July 17, 1938).

U.S. Census records for Charlotte, Mecklenburg County, NC (1900 and 1910), Memphis, Shelby County, TN (1920), Manhattan, New York County, NY (1930 and 1940).