The patented boat that won the war

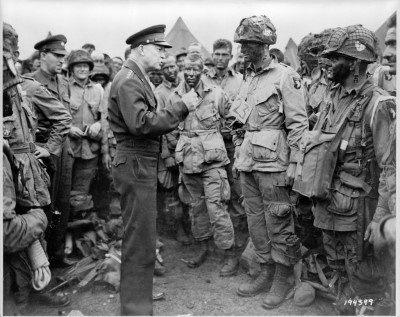

In the early hours of June 6, 1944, more than 135,000 Allied troops stormed the beaches of Normandy, in northern France. In spite of stiff resistance and heavy losses, the largest seaborne invasion in history prevailed, paving the way toward Nazi Germany’s surrender 11 months later.

This staggering logistical feat could not have succeeded without the efforts of a rough-and-tumble shipbuilder from New Orleans named Andrew Jackson Higgins.

7 min read

Each month, our Journeys of Innovation series tells the story of an inventor or entrepreneur whose groundbreaking innovation has made a positive difference in the world. Delve into the past to learn about one of history’s great innovators.

Born in Nebraska in 1886, Andrew Higgins had an unimpressive childhood. A Life magazine article from 1942 summed up his early years: “Two things seem almost certain: Higgins was interested in boats at a very young age, and he fought at the drop of a hat.”

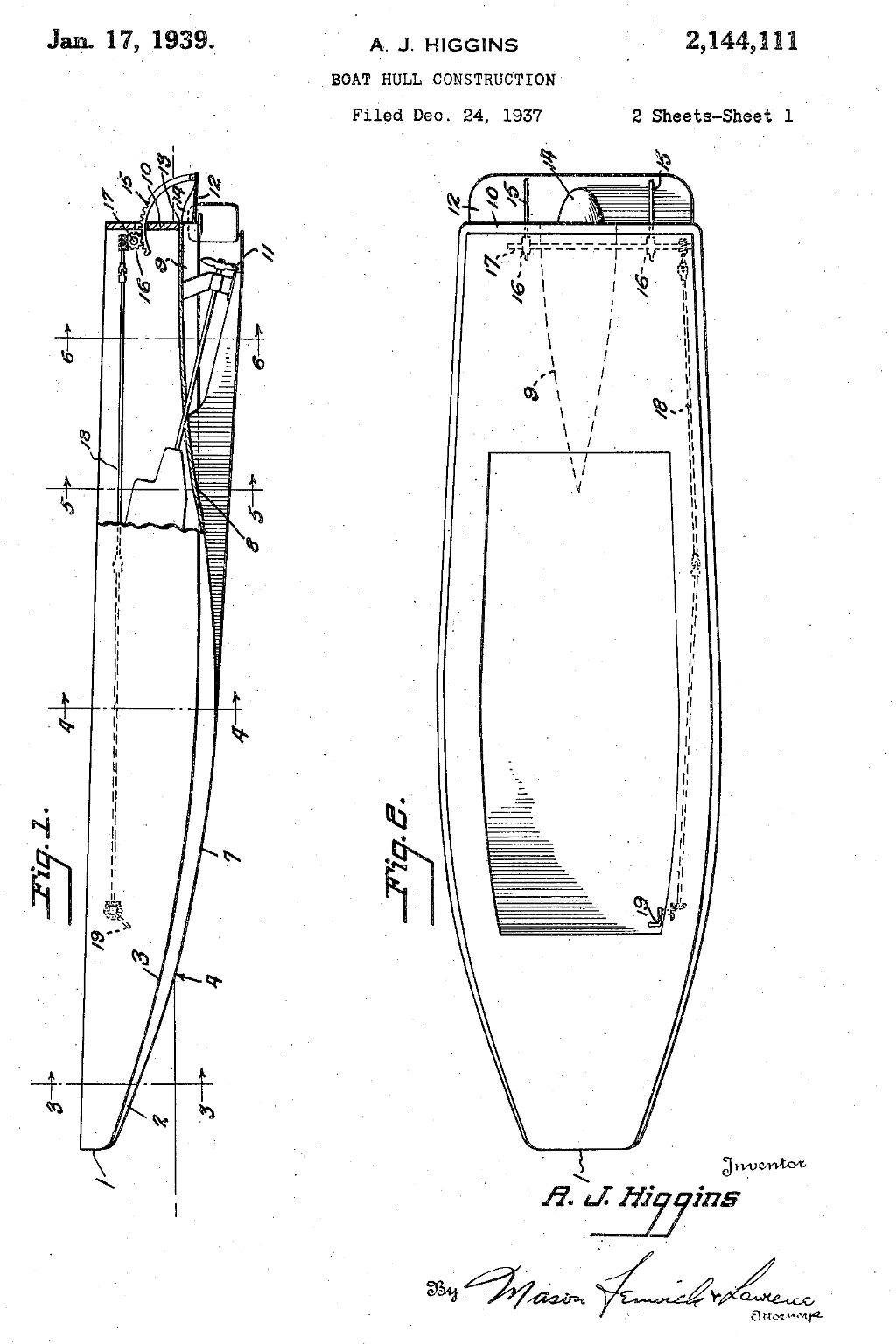

The patent for Higgins Industries “Eureka” boat

The brash young Higgins was often in trouble for brawling and would eventually drop out of high school. After a stint in the Nebraska National Guard, he left the state to work in the lumber industry on the Gulf Coast.

It was during his time there that Higgins first began to think about innovative boat designs to improve how the work gets done. While navigating the swamps and bayous, he conceived of a compact shallow-water boat that could remove and transport heavy logs through challenging, debris-laden waterways.

While improving his designs, Higgins bought a small boatyard in New Orleans and founded Higgins Industries. He branded his improved shallow-water boat, with characteristic flair, the “Eureka.” It would eventually form the foundation for the iconic Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (LCVP) or “Higgins Boat” that landed Allied troops not only at Normandy, but on the beaches of North Africa, Italy, and countless islands across the Pacific, as well as the German banks of the Rhine River in March 1945.

Throughout the 1930s, Higgins fought to establish his company’s reputation and convince a skeptical military establishment of the merits of his boat designs. He convinced the U.S. Coast Guard to buy his boats, which in turn drew the attention of the U.S. Marine Corps. At the time, the options available for amphibious landings were inadequate. Although the Marines lobbied the Navy to consider Higgins’ boats, Navy leaders were developing their own designs and were uninterested.

Undeterred, Higgins journeyed to the Navy’s Bureau of Ships in Washington, D.C., to argue for his designs. While there, he looked at the blueprints of the Navy-designed boat and scrawled on it, “This boat stinks – A.J.H.” After the Navy’s designs failed during trials, they finally agreed to test the Eureka boat. The ensuing trial proved Higgins’ design had the right stuff and led the Navy to award his small, little-known company with a contract to build landing craft for the military.

Andrew Jackson Higgins. Image courtesy of the National WWII Museum.

Higgins extended the Eureka into a series of military boats, including the Landing Craft, Personnel (LCP) and Landing Craft, Personnel (Large) or LCP(L). Higgins received U.S. patent no. 2,144,111 for boat hull construction on January 17, 1939. This patent protected the unique hull design that allowed his boats to land on beaches without getting their propellers stuck in the sand—a distinct military advantage that opened up many new options for planners to determine where to attack from sea. An early deficiency of the LCP(L), however, was that troops had to climb over its sides in order to disembark and unload supplies, exposing them to enemy fire.

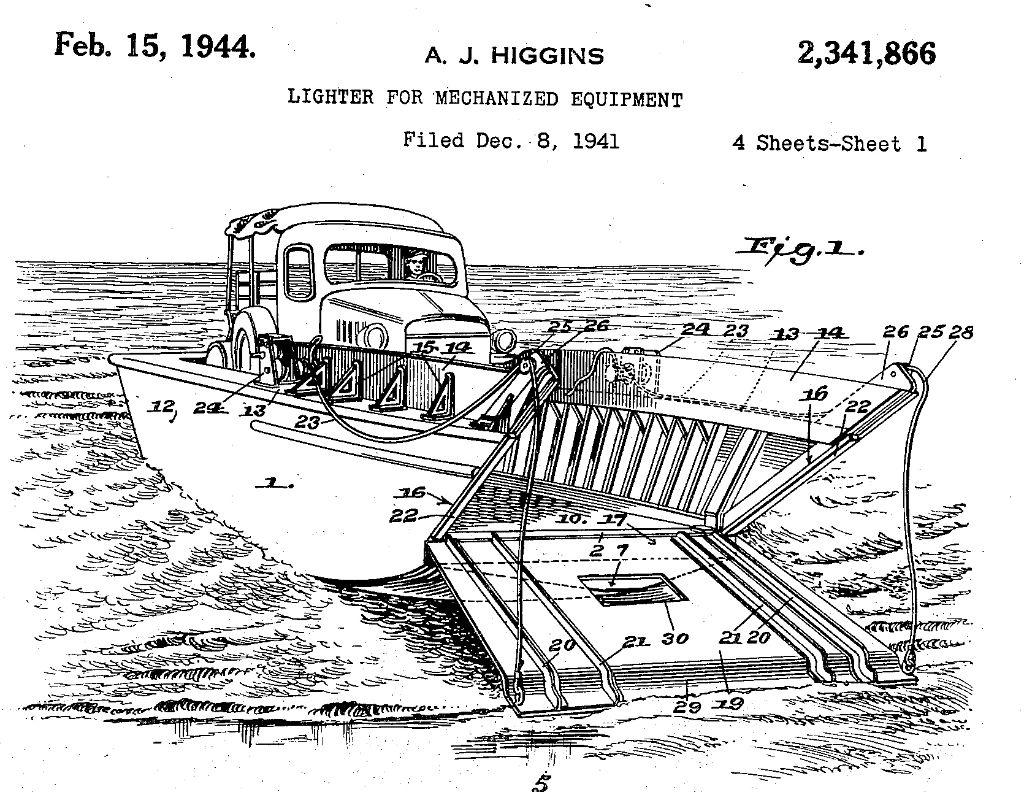

After learning of U.S. Marine Lieutenant Victor Krulak’s account of a Japanese landing craft with a retractable bow ramp during Japan’s 1937 invasion of China, Higgins modified his craft to include this feature. He filed for a patent on December 8, 1941, the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The LCVP’s ramp, protected by U.S. patent no. 2,341,866, would become America’s not-so-secret weapon for quickly offloading machinery and troops throughout the war.

U.S. Patent 2,341,866 filed December 8, 1941 and issued February 15, 1944

The LCVPs could be configured for various payloads—36 combat-equipped infantrymen, or a jeep and 12 troops, or 8,100 pounds of cargo—while maintaining the ability to float in three feet of water. Having solved a longstanding problem in warfare, the U.S. now turned to producing as many of these boats as possible. In this, Higgins’ own dynamic personality proved just as critical to the Allied war effort as his patented design. Even Hitler begrudgingly called him “the new Noah.”

“If Higgins had not designed and built those LCVPs, we never could have landed over an open beach. The whole strategy of the war would have been different.”

“Many people are puzzled by the fact that a man of Higgins’ drive and imagination did not amount to more before the war,” wrote Life in 1942. Indeed, America’s entry into the Second World War energized Higgins, a brawler by nature. With the “aggressive self-confidence of a heavyweight champion” he quickly opened new plants in anticipation of the military’s needs and exhorted his workers to churn out boats as fast as possible.

The Higgins Industry factory floor was a busy hive of activity. Photo courtesy of the National WWII Museum.

In the high rafters overlooking production floors, he hung huge banners that read, “The guy who relaxes is helping the Axis!”

“I operate in a big way and I don’t give a damn about money,” Higgins boasted to the Life reporter. As Higgins Industries’ production increased, the company expanded from one boatyard with 50 employees to seven plants employing more than 20,000 people.

Like fellow National Inventors Hall of Fame Inductee Henry Ford, Higgins developed assembly line techniques to meet demand. Higgins Industries would churn out more than 20,000 boats during the war, encompassing multiple designs, from heavy tank landers to speedy patrol boats. By 1943, an astounding nine out of 10 vessels in the U.S. Navy were designed by Higgins Industries.

This war bond poster depicts an amphibious landing, including a Higgins Boat unloading soldiers in the bottom right. Image courtesy of the Bangor Public Library.

Though famous for his profanity, “which when called into play flows as naturally as water from a spring, [and] is famous for its opulence and volume,” Life reported that his employees “admire him personally, hang on his words, and understand his blunt frankness.”

His employees had another reason to eagerly work at breakneck speed for Higgins: He would “take a chance on practically anybody with a plausible idea. His stable includes recent graduates of technical schools, inventors of national repute, and long shots picked up here and there.”

In spite of being (or perhaps because he was) tough, he was also fair, and he sought first and foremost ability in others. Higgins Industries was the first company in New Orleans to racially integrate, and Higgins paid all his employees equal wages for equal work, regardless of race or gender.

A former adviser of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Raymond Moley, wrote in a 1943 Newsweek article that “Higgins’ assembly line for small boats broke precedents, but it is Higgins himself who takes your breath away as much as his remarkable products and his fantastic ability to multiply his products at headlong speed. Higgins is an authentic master builder, with the kind of will power, brains, drive, and daring that characterized the American empire builders of an earlier generation.”

Higgins died in 1952, and Higgins Industries—once one of the most successful boat companies in the United States—closed its doors in 1959. But the legacy of Higgins and his patented boat lives on. Today, the National WWII Museum is located in New Orleans on Andrew Higgins Drive, a fitting tribute for an inventor and entrepreneur who played a key role in America’s victory.

Higgins was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in May 2019, and to mark the forthcoming 75th anniversary of D-Day, the National Inventors Hall of Fame Museum "landed" a restored Higgins Boat in front of the museum and United States Patent and Trademark Office headquarters in Alexandria, Virginia, on April 27. Through the end of July, visitors are invited to climb aboard and experience firsthand the boat that won the war.

Through the end of July 2019, visitors can climb aboard a restored Higgins Boat outside the National Inventors Hall of Fame and Museum at the USPTO headquarters in Alexandria, Virginia.

References

Andrain, Lewis. “Landing Craft: Naval Craft.” Encyclopedia Britannica, online. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, n/d. https://www.britannica.com/technology/landing-craft.

Burk, Gilbert. “Mr. Higgins and His Wonderful Boats.” Life Magazine, August 16, 1942.

Higgins, A.J. Boat hull construction. U.S. Patent 2,144,111 filed December 24, 1937 and issued January 1, 1939.

Higgins, A.J. Lighter for mechanized equipment. U.S. Patent 2,341,866 filed December 8, 1941 and issued February 15, 1944.

Strahan, Jerry, Andrew Jackson Higgins and the Boats That Won World War II. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1998.

National World War Two Museum. “New Orleans: Home of the Higgins Boats”. Accessed April 17, 2019.https://www.nationalww2museum.org/sites/default/files/2017-07/higgins-in-new-orleans-fact.pdf.