Making maternity wear fashionable

In 1939, Elsie Frankfurt and her sister Edna patented an adjustable skirt for pregnant women that soon became their new company’s most valuable asset. With the help of their younger sister, Louise, the three sisters became celebrities in their own right, famous coast to coast for designing, manufacturing, and marketing the most fashion-forward maternity clothes Americans had ever seen.

10 min read

Each month, our Journeys of Innovation series tells the stories of inventors or entrepreneurs who have made a positive difference in the world. This month’s story focuses on Elsie, Edna, and Louise Frankfurt. Their company, Page Boy, was the first to provide high-fashion alternatives to traditional maternity wear.

Left to right: Edna, Elsie, and Louise Frankfurt, 1950s. Frequently photographed for fashion magazines and society columns, the sisters became famous for their sense of style. (Courtesy of the University of North Texas College of Visual Arts + Design)

Sisters Elsie and Edna Frankfurt founded Page Boy, the country’s first high-end maternity-wear firm, in their hometown, Dallas, in 1937. The brains behind their first design, patented in 1938, was Elsie, five years younger than Edna, who oversaw the details of production and management. Their younger sister, Louise, soon joined the firm as its principal designer.

Although the sisters shared the burdens and triumphs of the enterprise, they developed certain recognizable tendencies and competencies, according to historian Kay Goldman, whose book on Page Boy uncovers how the three women divided the tasks that piled up over the course of six successful decades of operation. Elsie was the glamorous wheeler-dealer, the face of the company. By the 1950s, she had become nationally famous for her eloquence, charisma, wit, and fashion sense. Just as fashionable, Edna nonetheless spent most of her time behind the scenes, keeping the factory running and the shops selling. Louise ran the design studio and turned out season after season of appealing, inventive, and comfortable apparel.

"Appealing" and "inventive" hadn’t been words associated with maternity wear before the Frankfurt Sisters transformed the industry. The first major ready-to-wear maternity clothes manufacturer and marketer had been Lane Bryant, founded in 1904, but their products did not quite resemble normal women’s wear. The main difference was the hemline of the skirt, which crept higher and higher in front as the wearer’s pregnancy progressed. In the 1920s, as incomes increased, hemlines rose, and more and more women pursued lives outside the household, the demand for fashionable pregnancy attire exploded. Yet, the uneven skirt, longer in back than in front, stopped expectant mothers from blending in with the other career women and flappers, as the independent, fashionable young women of the Jazz Age were called.

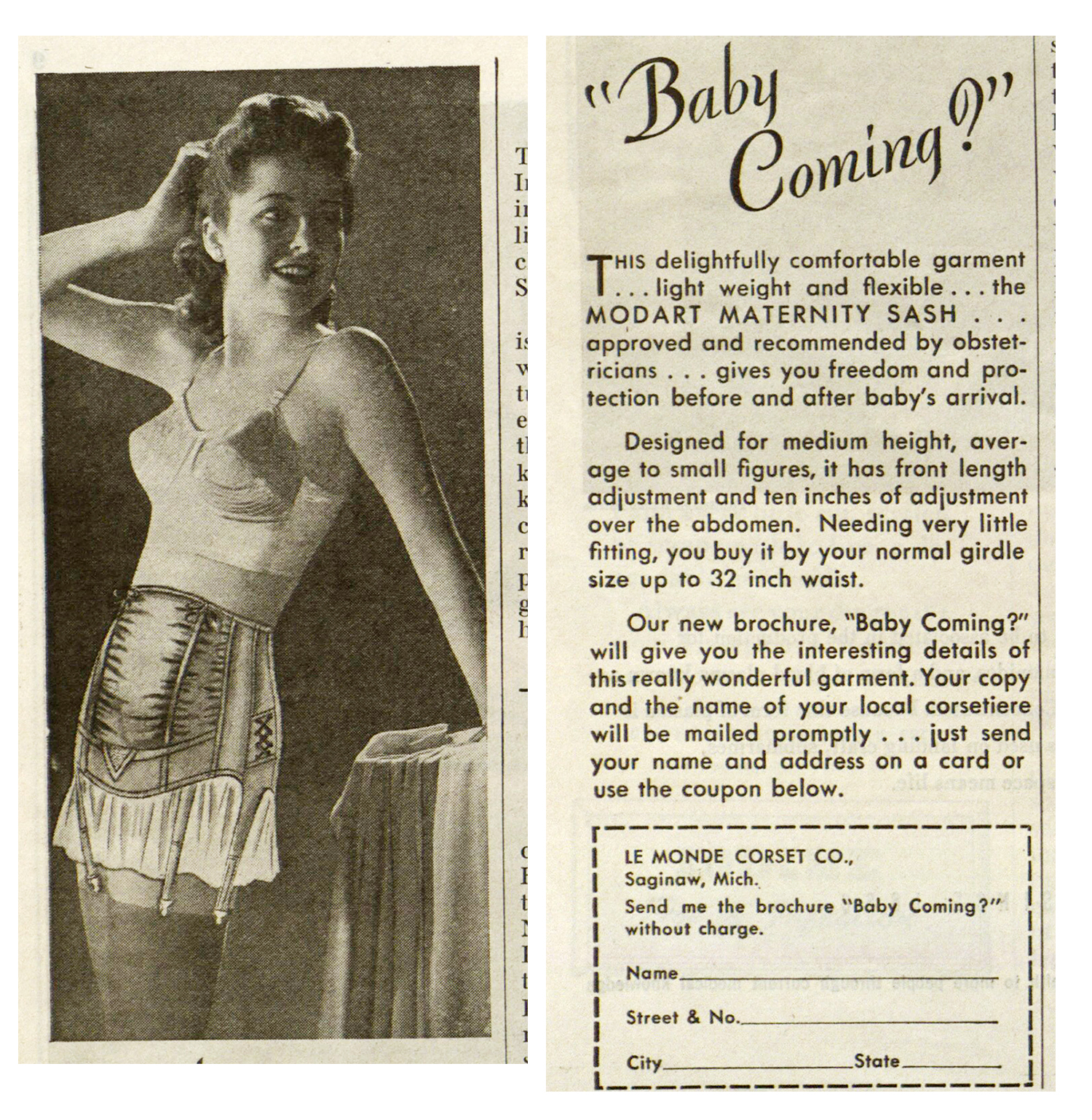

Advertisements of the 1920s and '30s encouraged all women to wear structuring undergarments that concealed rather than accommodated pregnancy. The Frankfurt sisters would reverse that trend, producing garments that accounted for the wearer’s changing measurements.

Through much of the 20th century, pregnant women wore structuring undergarments like this 1934 pregnancy girdle to avoid the appearance of an expanding abdomen. (Courtesy of Bernard Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine)

A solution to the skirt problem occurred to Elsie when Edna became pregnant. It was 1937, and Elsie told her sister––charitably, we hope—that she looked a bit like a “beachball in an unmade bed.” The problem wasn’t pregnancy as such, Elsie explained, but the lack of good options for flattering pregnancy fashions. In keeping with the styles of the day, Elsie decided to craft a two-piece suit for her sister. A tailored, pleated jacket would cover the skirt, where the real innovation lay. There, Elsie had engineered a hole, or window, in the front of the skirt, just under the waistband. Concealed by the jacket, the window could be expanded with a system of drawstrings. That took care of the protruding abdomen but did so much more, too. The adjustable window at the waist kept the line of the hem parallel to the ground.

Elsie had solved a perennial annoyance of pregnancy for women in 20th-century America: that pesky uneven hemline, higher and higher in the front as nine months progressed.

Like most successful inventors, Elsie made a prototype and tried it out on a willing subject, in this case Edna. She was thrilled, and the two set out right away to build a business selling Elsie’s creation. They rented a workshop and hired a couple of seamstresses. The first customers were the sisters’ friends who had already been admiring Edna in the navy blue, two-piece prototype. Edna and Elsie used the money from these early sales to rent retail space in Dallas’s Medical Arts Building, where expectant mothers visiting their doctors for checkups would be sure to encounter Page Boy’s first store.

They named the company “Page Boy” after the historical heralder of good news at a royal court: the expectation of an heir. The company name would be the first of many creative and playful forays into marketing, fuel for Page Boy’s meteoric rise in later years.

Another ingredient to success was U.S. Patent No. 2,141,814 for a “maternity garment ensemble,” the skirt-with-window and pleated jacket outfit. Elsie and Edna had filed it on June 3, 1938, six months after the opening of the Medical Arts Building store. Granted on December 27, 1938, the patent protected the young firm’s only asset, the skirt that kept a straight hemline throughout the wearer’s pregnancy. The Page Boy brand became an asset, too, the sisters realized later, when they registered Page Boy and Page Boy Maternity as U.S. trademarks (Registration Nos. 1,712,391, 1,716,739, and 1,722,044).

Elsie and Edna Frankfurt received U.S. Patent No. 2,141,814 on December 27, 1938, for a maternity garment ensemble.

The Page Boy brand reached department and specialty stores across the United States in 1939, with newspapers from New York to California advertising the new “adjustable skirt,” the sisters’ patented design. In 1940, Elsie and Edna decided to open a second store, on a fashionable stretch of Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles. To run the store, Edna took up residence there, along with her husband and two children. Now involved in the business, the youngest Frankfurt sister, Louise, joined Edna and established a workshop behind the store. Elsie was never away for long, flying in frequently from Dallas to help and advise. Together, they planned store openings in the Southeast, Midwest, and Northeast.

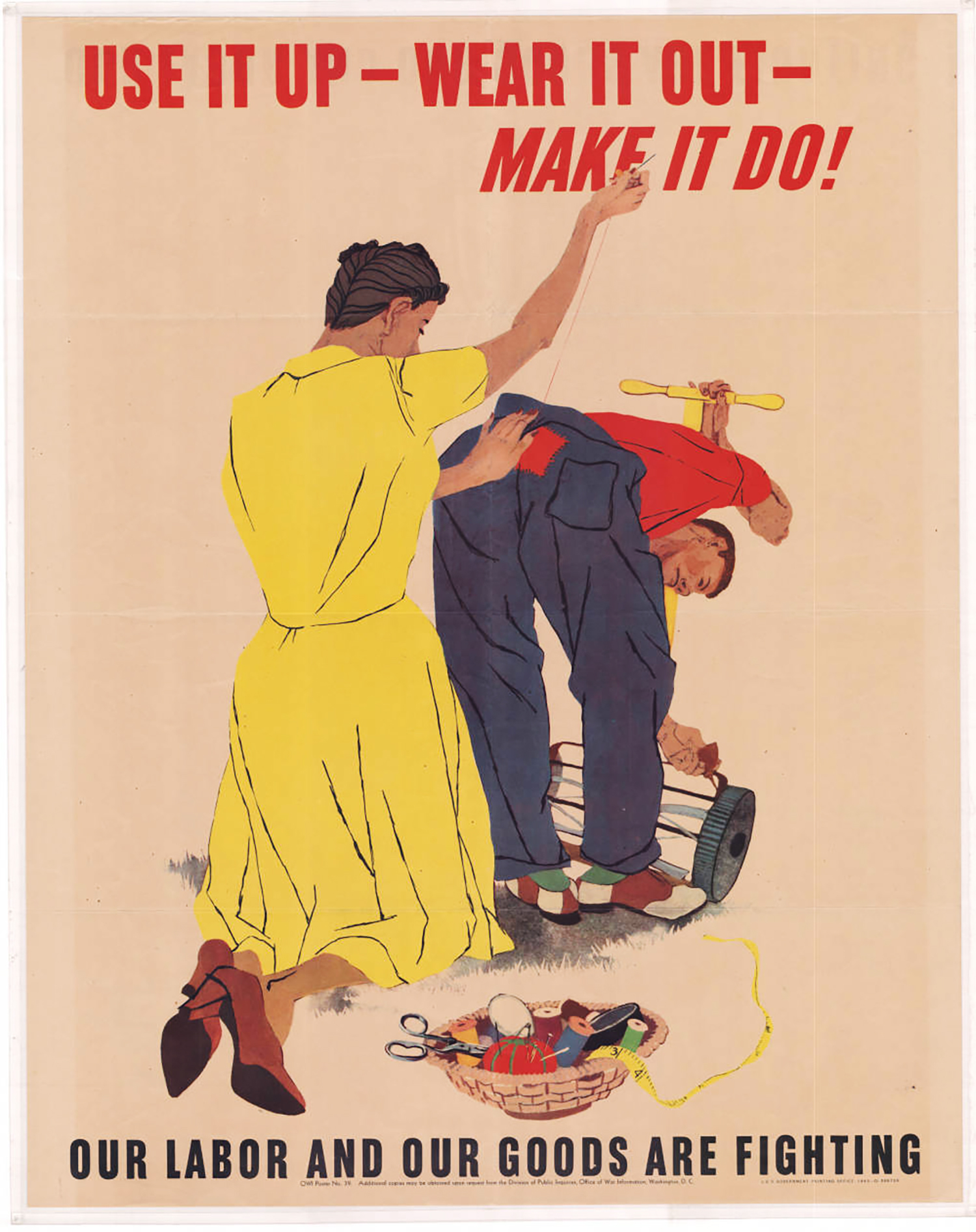

During World War II, regulations limited the use of fabric by clothing firms. In addition, the U.S. government printed posters like this one, from 1943, to encourage people to repair and repurpose the materials they already had. Nevertheless, Page Boy adapted and thrived in the wartime business environment. (Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina).

World War II slowed this progress but didn’t halt it. Rationing added to Elsie’s difficulties in securing fabric, but she had already established relationships with New York City garment merchants—relationships that became indispensable when materials became harder to get in 1942.

The war produced other challenges, too, and not just on the production side. Laws and regulations of 1943 forced Page Boy to change how it marketed its best-selling product, the two-piece suit with adjustable skirt. To encourage consumers to buy only what they needed and nothing more, the government now forbade the sale of multi-piece suits, meaning that Page Boy’s skirts and jackets had to be sold separately, leaving mismatched items in the inventory at the end of each season. The inventory became trickier to move, too, since the government restricted distribution to established customers in an effort to limit the resources used for consumer goods. Elsie, Edna, and Louise were not allowed to sell to any new department or specialty stores until the end of the war.

Perseverance paid off in the late 1940s. The postwar baby boom favored businesses like Page Boy. Orders increased, and by 1947, Page Boy had grown to 100 employees, almost all of them women. Two years later, they all moved into a sparkling new headquarters and factory in Dallas. A showroom and library catered to customers in search of merchandise and information related to pregnancy and child-rearing. Neiman Marcus Galleries, another Dallas firm, outfitted the public-facing rooms and offices in the Hollywood-chic idiom.

At this point, visual references to Hollywood made perfect sense for Page Boy. Elsie, Edna, and Louise had learned to leverage celebrity patronage for advertising materials and publicity initiatives. The Page Boy catalogue, which looked more like a fashion magazine than a trade publication, touted famous customers like Elizabeth Taylor, Lucille Ball, Judy Garland, and Grace Kelly. In the late 1950s, Jaqueline Kennedy became a customer, too, but the Frankfurt sisters were more discreet when it came to the glamorous wife of a future president. Although she spoke to the press about Mrs. Kennedy’s influence on the fashion industry and Page Boy’s designs, Elsie was careful in the early 1960s to keep the First Lady’s status as a Page Boy customer under wraps.

Jacqueline Kennedy wore this Page Boy maternity dress in 1960 during her husband’s presidential campaign. (Courtesy of the University of North Texas College of Visual Arts + Design)

Elsie herself, and not Jaqueline Kennedy, became the firm’s glamorous face. A fashion maven and style icon, Elsie made regular appearances on the Today Show and other nationally syndicated programs. She used these platforms to make spirited arguments for women’s rights, especially married women’s. In 1958, she told viewers of “Night Beat: Probe” that married women in Texas lacked direct and decisive access to their own property and income. Why on earth should a woman’s husband have to approve the investments she made with her own money? Elsie’s feminism came from the heart—that is, from personal experience.

“I live in a state where my sister [Edna] …. Had to get her husband’s consent, and she still does, if she wants to invest any of her own money,” Elsie told a journalist for a Family Weekly article about American women’s legal status as second-class citizens.

The increasing number of pregnant women choosing to continue to work in offices, and therefore needing fashionable pregnancy outfits, helped Page Boy thrive even after the baby boom had ended. The sisters kept their brand fresh and young by enlisting a new generation of celebrity collaborators like Marianne Faithfull, who designed a line of Page Boy maternity wear in 1965 while she was pregnant herself.

Nevertheless, in the 1970s and ’80s, new competitors arrived on the scene and used corporate financing and economies of scale to outperform the Frankfurt sisters’ family operation. With the sisters in their seventies and eighties and ready to retire, a maternity-wear conglomerate acquired Page Boy in 1993 but decided to discontinue the brand.

To replace the ill-fitting, uncomfortable options of the 1930s, they made pregnancy fashionable for the first time in U.S. history. From Page Boy’s own catalogue, the first to connect pregnancy to glamor, sprang a new cultural phenomenon that’s still with us in celebrity and fashion magazines and on social media the world over: a woman who’s pleased, finally, to show on camera the range of fashions available to her while she’s expecting. In today’s crowded market for maternity wear, the Frankfurt sisters’ accomplishments are clear. Elsie, Edna, and Louise transformed an industry, created jobs, and empowered women in the workplace and beyond.

Through the decades, depicted here in catalogue covers from the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, Page Boy kept maternity wear at the cutting edge of fashion. (Courtesy of the University of North Texas College of Visual Arts + Design)

Credits

Produced by the USPTO’s Office of the Chief Communications Officer. For feedback or questions, please contact inventorstories@uspto.gov.

Story by Adam Bisno. Contributions from Sarah Arnold and Jay Premack. Special thanks to Edward Hoyenski, Annette Becker, and Laura Larrimore. All quotes come from Kay Goldman, Dressing Modern Maternity: The Frankfurt Sisters of Dallas and the Page Boy Label (Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press, 2013). The image at the beginning of this story shows Edna (standing, left), Elsie (standing, right) and Louise (seated) with a sketch of their new headquarters, constructed in the late 1940s (courtesy of the Dallas Historical Society).

References

Faust, Mary-Eve, “Pregnant Women: Understanding Pregnant Women’s Shape, Sizing and Apparel Style Preferences,” in Designing Apparel for Consumers: The Impact of Body Shape and Size, eds. Marie-Eve Faust and Serge Carrier (Oxford: Woodhead, 2014), 235-53.

Fisher, Michelle Millar, and Amber Winick, Designing Motherhood: Things that Make and Break Our Births (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021), 10, 103-5.

Goldman, Kay, Dressing Modern Maternity: The Frankfurt Sisters of Dallas and the Page Boy Label (Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press, 2013), 2-5, 20-45, 47-60, 67-68, 82-83, 89, 91-94, 96, 106, 109, 129-31, 135.

Ornish, Natalie, Pioneer Jewish Texans (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2011), 200-1.

Rich-McCoy, Lois, Millionairess: Self-Made Women of America (New York: Harper & Row, 1978), 97-102.