Inventing salsa

Johnny Pacheco popularized a New York version of Cuban dance music by founding a label, Fania Records, and a troupe of performers, the Fania All Stars, in the 1960s. He called it all “salsa”—the music, the dancing, the culture as a whole—and the term has stuck. Through salsa, Pacheco and Fania achieved lasting recognition for performers from the United States’ growing Latino communities and created a worldwide market for Latin dance music.

11 min read

Each month, our Journeys of Innovation series tells the stories of inventors or entrepreneurs who have made a positive difference in the world. This month’s story focuses on Johnny Pacheco, musician and founder of Fania Records, the label that created the first “salsa craze” and brought Latin dance music to the masses.

“One thing I believe is that once you have a formula, you don’t change it,” said the man who gave Latin dance music its mass appeal. Johnny Pacheco, a musician himself, founded Fania Records in 1964. The company became an entertainment empire that vaulted him and a generation of Latin musicians to stardom. In the process, Pacheco and Fania’s other artists transformed an Afro-Caribbean style of dance music specific to Latin communities in New York City into a globally distributed genre almost universal in its appeal. Pacheco’s Fania Records even supplied a name for this sound and culture: “salsa.”

”Salsa” (literally, “hot sauce”) denoted a style of Latin dance music that seemed to have appeared quite suddenly. In fact, only the name was new. The genre had roots in colonial Cuba and mid-20th-century New York. Then, in the late 1960s, as Latin music became ever more popular among New York audiences, Pacheco and his business partner selected the word “salsa” as the genre's convenient, memorable, marketable identifier. The name became part of a much larger strategy that transformed salsa into a national and then international phenomenon.

Pacheco had been born in Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic, in 1935, and at a young age learned from his father, a musician and bandleader, how to play several instruments, including the clarinet, the saxophone, and the accordion. In 1946, the family immigrated to the United States, where young Pacheco’s musical education expanded to still more instruments.

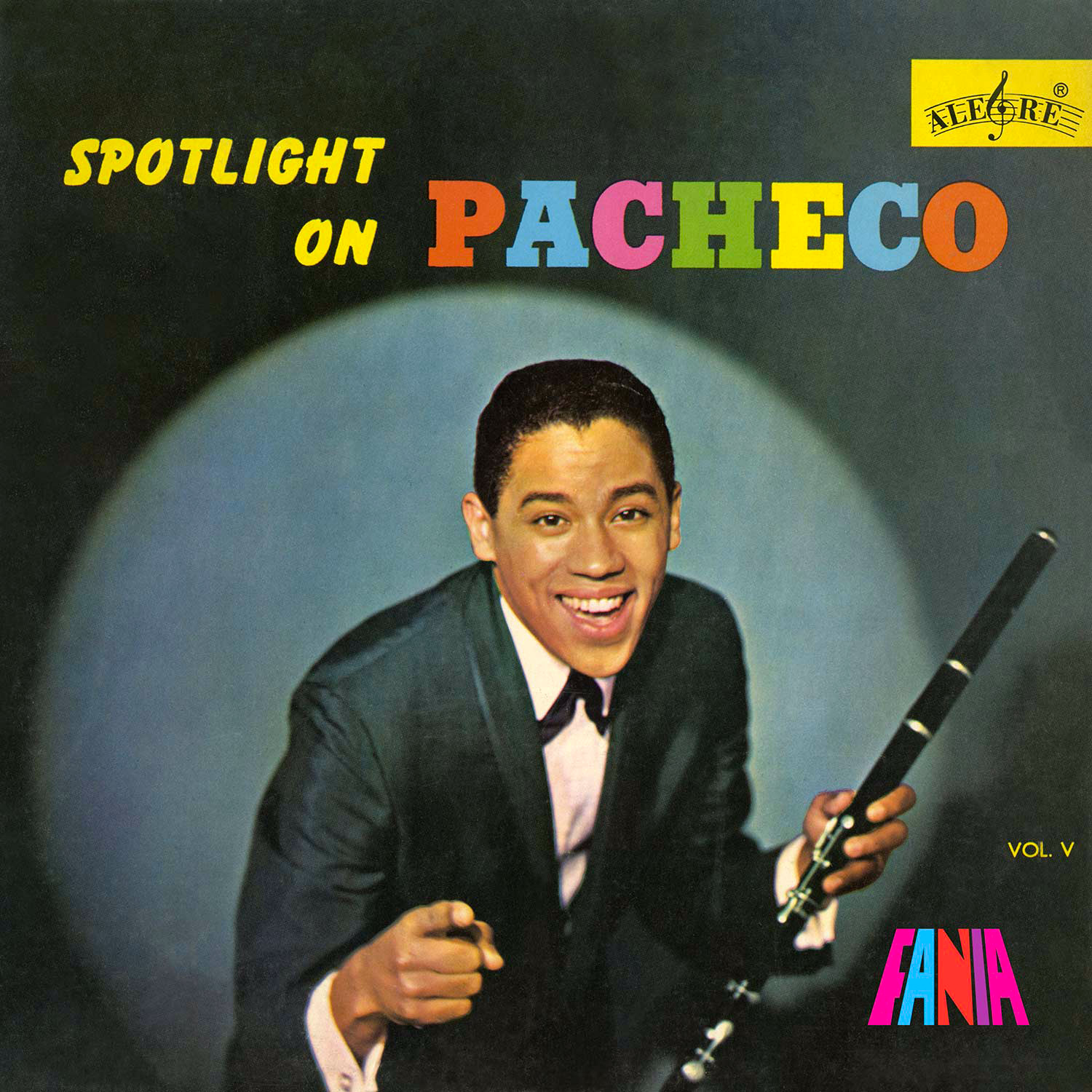

Johnny Pacheco’s first album, “Spotlight on Pacheco,” came out under the Alegre label in 1961 and helped make him a star. Fania Records, courtesy of Craft Latino Recordings, a division of Concord.

The Juilliard School, New York’s prestigious music and performing arts conservatory, recognized Pacheco’s talents and efforts with a scholarship to study composition and theory. During his education and afterward, Pacheco played percussion and other instruments in New York City’s Latin dance orchestras, eventually forming one of his own. He found his greatest early success as a flutist—a success he advertised on the cover of the 1961 album “Spotlight on Pacheco,” which sold more than 100,000 copies.

“Spotlight on Pacheco” reflects its particular moment on the Latin music and dance scene in New York, then dominated by Cuban-derived musical styles. Pacheco nearly perfected this African and Western mix of melodies, rhythms, and instruments that recalled the heritage of the Caribbean’s diverse populations.

In the decades around World War II, as more and more people from the Caribbean, especially Puerto Rico, had moved to New York City, they had brought this distinctive musicality with them. One of Pacheco's contemporaries and collaborators remembered of East Harlem in the 1960s that men and boys could be found all over, “keeping time and pounding out rhythms on whatever was in sight”—evidence of “a special kind of inheritance that’s in our blood.”

Many of Fania’s artists came from this neighborhood and sang of the challenges and rewards of life there. In the 1960s and ‘70s, the migration of Spanish-speaking people to New York increased, ensuring a ready supply of musicians and audience members for Latin dance music like Pacheco’s.

There were still other factors leading to Pacheco’s success as a musician and later record producer. The decline of big band music in the 1960s opened a space for smaller ensembles and novel approaches. By reducing the number of musicians and concentrating them in a tight frontline of two flutists, a trumpeter, and a trombonist, Pacheco arrived at a sound that was inexpensive to produce yet distinctive to the ear. New York audiences loved the results: a recognizably Cuban sound, bright and loud. Meanwhile, the embargo on trade with Cuba of the early 1960s protected record producers like Pacheco from competition with that country’s labels.

In the right place at the right time, Pacheco teamed up with a lawyer, Jerry Masucci, and founded Fania Records in 1964. Where they got the name is uncertain. It might have referred to a popular music hall in Havana, or it might have come from song lyrics by the Cuban musician Reinaldo Bolaño.

The label’s first album was Pacheco’s “Cañonazo,” an instant hit. For years, even after Fania had released several more albums, “Cañonazo” remained its bestseller. The operation nonetheless remained small, with Pacheco himself distributing records from the trunk of his car and running the company from his apartment.

Two years into the venture, Pacheco and Masucci decided to expand by finding and signing new artists to the label. The first to join were Larry Harlow, a Jewish-American musician playing in the Cuban tradition, and Bobby Valentín, a Puerto Rican bandleader especially skilled in crafting new arrangements. Then came Willie Colón, a trombonist and emerging visionary, who brought cutting-edge experimentation to Fania’s burgeoning sound.

Clockwise from top left: Larry Harlow, Willie Colón, and Bobby Valentín, early 1970s. Fania Records, courtesy of Craft Latino Recordings, a division of Concord.

A distinctive “Fania sound” was already audible to discerning listeners by the late 1960s. Vocals tended to feature higher-pitched choruses with a nasal inflection. Trumpet solos ended with an upward flourish. Riffing and improvising in the studio even preserved some of the spontaneity and electricity of jam sessions at Latin music and dance venues in New York City.

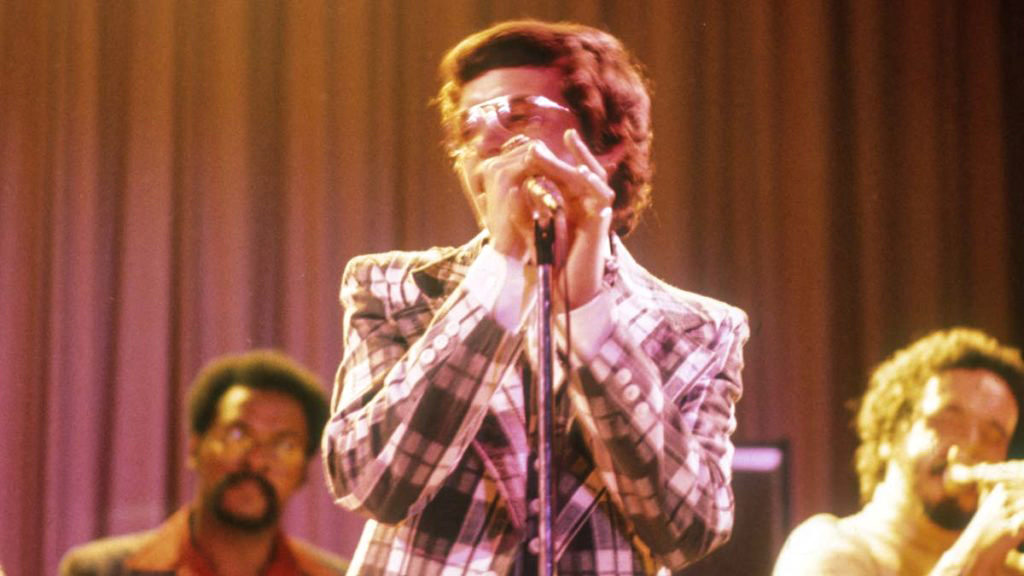

Héctor Lavoe mid-performance, early 1970s. Lavoe was born and raised in Puerto Rico and came to New York as a young man with the express intent to make it as a musician there. Fania Records, courtesy of Craft Latino Recordings, a division of Concord.

The sound emanating from these venues, reproduced and publicized by Pacheco’s label, contributed to the formation of Fania’s distinctive brand. The next step was for Pacheco and Masucci to protect it. On July 5, 1968, they filed a trademark application for the name “Fania” and obtained registration the following year (U.S. Trademark No. 873,009).

Next, Fania signed Puerto Rican singer-songwriter Héctor Lavoe, whose albums “El Malo” (“The Bad Guy,” 1969), “The Hustler” (1969), and “Cosa Nuestra” (a collaboration with Willie Colón and marketed in English as “Our Latin Thing,” 1971) traded on the Fania sound and became instant classics.

Meanwhile, Pacheco added still more artists to Fania’s roster, including Rubén Blades, Celia Cruz, and Eddie Palmieri. Pacheco oversaw the marketing for these performers, especially the vocalists, whose inspired renditions attracted ever larger audiences.

Pacheco next formed a troupe of gifted Latin bandleaders and performers and called it the Fania All Stars (U.S. Trademark No. 3,614,324). In August 1971, the All Stars performed to a crowd of 4,000 at New York’s Cheetah Club. In the fall of 1973, they sold out Yankee Stadium.

This publicity photograph of Celia Cruz was taken in 1962, shortly after her arrival in the United States from Cuba, where her career had begun. Collection of the Library of Congress.

As it gained in popularity, salsa took on new meanings and new associations—a life of its own. It connoted a certain urban lifestyle and migrant experience, yet eluded a fixed definition. It encompassed cultures of race, class, and gender particular to Spanish-speaking peoples all over the world, even as it retained close associations with the Nuyorican experience in particular (“Nuyorican” is a blend of “New Yorker” and “Puerto Rican”).

In their branding of the genre, Pacheco and Fania resorted to documentary filmmaking. The 1971 concert at the Cheetah Club resulted in “Our Latin Thing,” which opens to rooftop and street scenes in New York City. Afro-Caribbean beats increase in volume as Nuyorican children play. Then the opening credits roll, the performers’ names splashed as graffiti across the crumbling walls of tenement houses. Salsa, in this iteration, has its place: the “barrios,” neighborhoods like East Harlem, the gritty but also grand epicenter of Nuyorican culture.

As Fania continued its bid for mass appeal through the later 1970s, however, its filmmakers and marketers worked to obscure the East Harlem connection, trying as they were to make salsa a genre with universal appeal.

Pacheco balanced this push for national and international appeal with an emphasis on the “Fania family,” which embraced the label’s musicians and audiences as well as Latin communities all over the world. In this way, Pacheco and his artists capitalized on the growth of the Spanish-speaking population in the United States and Latinos’ increasing prominence in mainstream American culture.

This 1967 photograph by Bernard Gotryd, which he titled “El Barrio” (“The Neighborhood”), shows a street corner in East Harlem (also known as Spanish Harlem), the part of Manhattan that lent early salsa music its sense of place. Collection of the Library of Congress.

By the middle of the 1970s, Fania was producing nearly 80% of the salsa records for sale in the United States, and mainstream media took notice. Articles in popular magazines acquainted non-Latinos with Fania’s sound and roster, and network television began to feature performances by members of the Fania All Stars. Throughout, Pacheco emphasized the Latin element: “The Whites had their music, the Blacks had Motown, and here we come with Fania. But it was Latino.”

For many Latinos in the United States, especially Puerto Ricans, salsa formed a pillar of Latin identity. Héctor Lavoe’s “Mi gente” (“My people”) indeed became a kind of “Nuyorican national anthem,” according to fans, and inspired feelings of connectedness to a larger community. For years, music had been a binding agent among the mix of ethnicities represented by New York’s Spanish speakers. Now, thanks to Fania, the music had a name and an appeal among national and even international audiences.

In 1974, the Fania All Stars performed for the first time in Venezuela, an untapped market for salsa music. The concert was a success, pulling together an audience for future acts and creating a market for American and Venezuelan salsa records. Pacheco made Caracas a regular stop on All Stars tours and performed there himself at sold-out venues. The pattern repeated itself in Colombia, too, establishing a large market there for salsa—and Fania—by the end of the 1970s.

The Fania All Stars in Caracas, Venezuela, 1980. By this point, Pacheco had been sending the troupe to South America on a regular basis for six years. Fania Records, courtesy of Craft Latino Recordings, a division of Concord.

Fania’s records also attained a following in sub-Saharan Africa. In 1974, Pacheco, Celia Cruz, and others attended a massive music festival in Zaire with the likes of James Brown, B. B. King, and the Pointer Sisters. Thousands of people (many chanting “Pa-che-co! Pa-che-co!”) greeted the Fania All Stars at the airport as they climbed out of the plane. The festival resulted in an Academy Award-winning film by Leon Gast, which further raised Fania’s profile at home.

In the mid-1970s, Pacheco’s business partner, Masucci, began to push Fania’s music toward mainstream tastes and worked in other ways, too, to boost record sales outside American coastal cities and Latin communities. He even signed a contract with CBS to have its label, Columbia Records, produce and distribute the Fania All Stars’ albums. Many of these would go abroad, to Europe especially, where Masucci hoped to make inroads, and eventually to Japan and other parts of Asia.

Later in the 1970s, Fania’s salsa boom began to affect mainstream music in unforeseen, exciting ways. Salsa became a principal ingredient in genres enjoyed by people who tended not even to have a passing familiarity with the Fania sound. Patti LaBelle’s audiences would hear it in a track on “Tasty,” her wildly successful album of 1978. The song, “Me Gusta Tu Baile/Teach Me Tonight” (“I Like Your Dance”), featured a brass-forward sound and prominent saxophone that could have come right from Fania’s music sheets. The nasality and pitch of the chorus echoed Fania’s vocals; the percussion and piano anchored the song in the Fania sound.

Eventually, salsa became bigger than any one record label could contain. In the 1980s, as the genre diversified and expanded, labels other than Fania entered the mix and supplanted the original. Masucci and Pacheco eventually sold Fania to South American investors but continued to be involved—Masucci on the business side, Pacheco on the artistic side.

Pacheco kept performing with the Fania All Stars into the 21st century. The label he created—and trademarked—changed hands several more times, its 1,000 albums, 3,000 compositions, and 10,000-plus master tracks lovingly maintained for posterity and periodically re-released to new generations of salsa lovers all over the world.

Credits

Produced by the USPTO’s Office of the Chief Communications Officer. For feedback or questions, please contact inventorstories@uspto.gov.

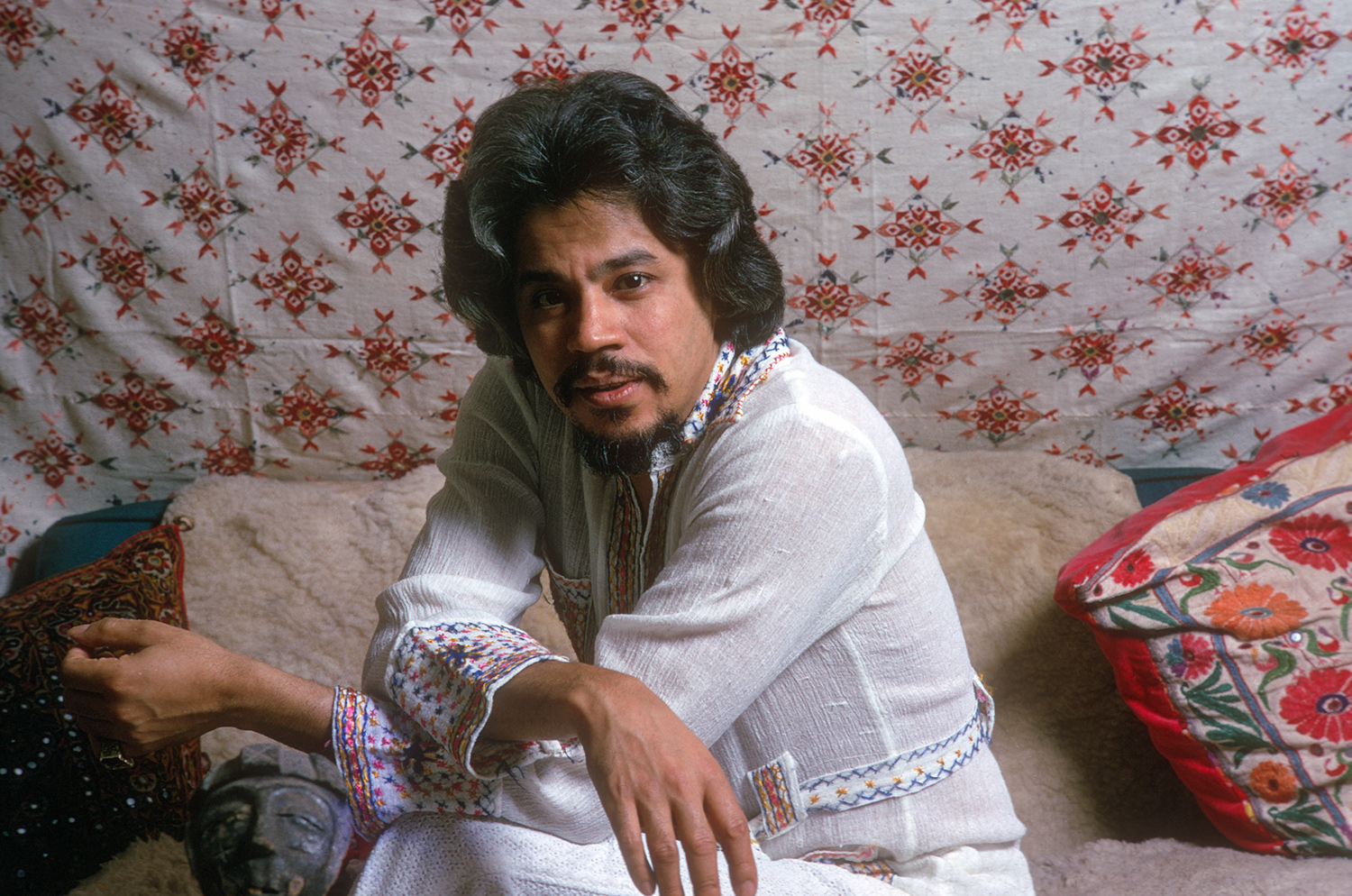

Story by Adam Bisno. Contributions from Marie Ladino. The photograph of Johnny Pacheco at the beginning of this story was supplied by Fania Records, courtesy of Craft Latino Recordings, a division of Concord.

References

Aparicio, Frances R., Listening to Salsa: Gender, Latin Popular Music, and Puerto Rican Cultures (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1998), 65-67, 92-93.

Entries by Anna Kijas (“Fania Records”), Raúl Fernández (“Salsa”), Gregory McNamee (“Pacheco, Johnny”), in Latin Music: Musicians, Genres, and Themes, ed. Ilan Stavans (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2014), 1:261-63, 2:585-87, 2:693-98..

Essays by Wilson A. Valentín Escobar, Robin Moore, Medardo Arias Satizábal, Christopher Washburne, and Lise Waxer, in Situating Salsa: Global Markets and Local Meanings in Latin Popular Music, ed. Lise Waxer (New York: Routledge, 2002), 3-4, 58, 62, 102, 176, 226-29, 254.

Flores, Juan, Salsa Rising: New York Latin Music of the Sixties Generation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 100, 103-4, 109-10, 178, 182-95, 217.

Manuel, Peter, with Kenneth Bilby and Michael Largey, Caribbean Currents: Caribbean Music from Rumba to Reggae (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006), 90-95, 103-4, 106.

Marks, Morton, “The East Harlem Music School: Music of the Urban Caribbean,” report prepared for the Ethnic Heritage and Language Schools Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, July 1982, www.loc.gov/item/afc1993001_22_001/.

Palmieri, Eddie, interview conducted by the Library of Congress, April 12, 2021, www.loc.gov/static/programs/national-recording-preservation-board/documents/Interview_Eddie-Palmieri.pdf.

Roberts, John Storm, The Latin Tinge: The Impact of Latin American Music on the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 144-45, 155, 160-64, 166, 172, 186-88, 209, 220, 223-24.

Rondón, César Miguel, A Chronicle of Urban Music from the Caribbean to New York City, trans. Frances R. Aparicio (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 9, 38-43, 47, 52-53, 60, 64, 95, 100, 103-4.

Waring, Charles, “Fania Records: How a New York Label Took Salsa to the World,” published January 13, 2021, www.udiscovermusic.com/stories/fania-records-story/.