A legacy of love, loyalty, and laughter

A natural optimist, toy inventor Eddy Goldfarb overcame early loss, financial hardships, and professional setbacks to become an independent inventor that created some of the most popular mechanical toys of the 20th century. Now a centenarian with nearly 300 patents to his name, Goldfarb credits his longevity to his love of tinkering and writing.

20 min read

Each month, our Journeys of Innovation series tells the stories of inventors or entrepreneurs who have made a positive difference in the world. This month, Whitney Pandil-Eaton's story focuses on iconic toy inventor Eddy Goldfarb, who has created more than 800 items over his 80-year career including Yakity-Yak Talking Teeth, KerPlunk, Stompers, and a bubble gun, among others.

Do you know an innovator or entrepreneur with an interesting story?

It’s 1944, and the world is at war.

Thousands of miles from home in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, 23-year-old Eddy Goldfarb sits hunched over in the cramped radio room of the USS Batfish, sketching diagrams and jotting down descriptions in a small notebook under the incandescent light of a 40-watt bulb. It is in this room — the size of two telephone booths — that Goldfarb can temporarily escape the noise and chaos of the war that rages in the water and skies above him.

Setting the notebook down, he pulls out a spool of magnetic wire, paperclips, and a dry cell battery from the cabinets next to him. Using a soldering iron, Goldfarb combines these items to make a tiny direct current electric motor, like those used in toys. He tinkers with one and then another until it’s time to head back to the conning tower to work.

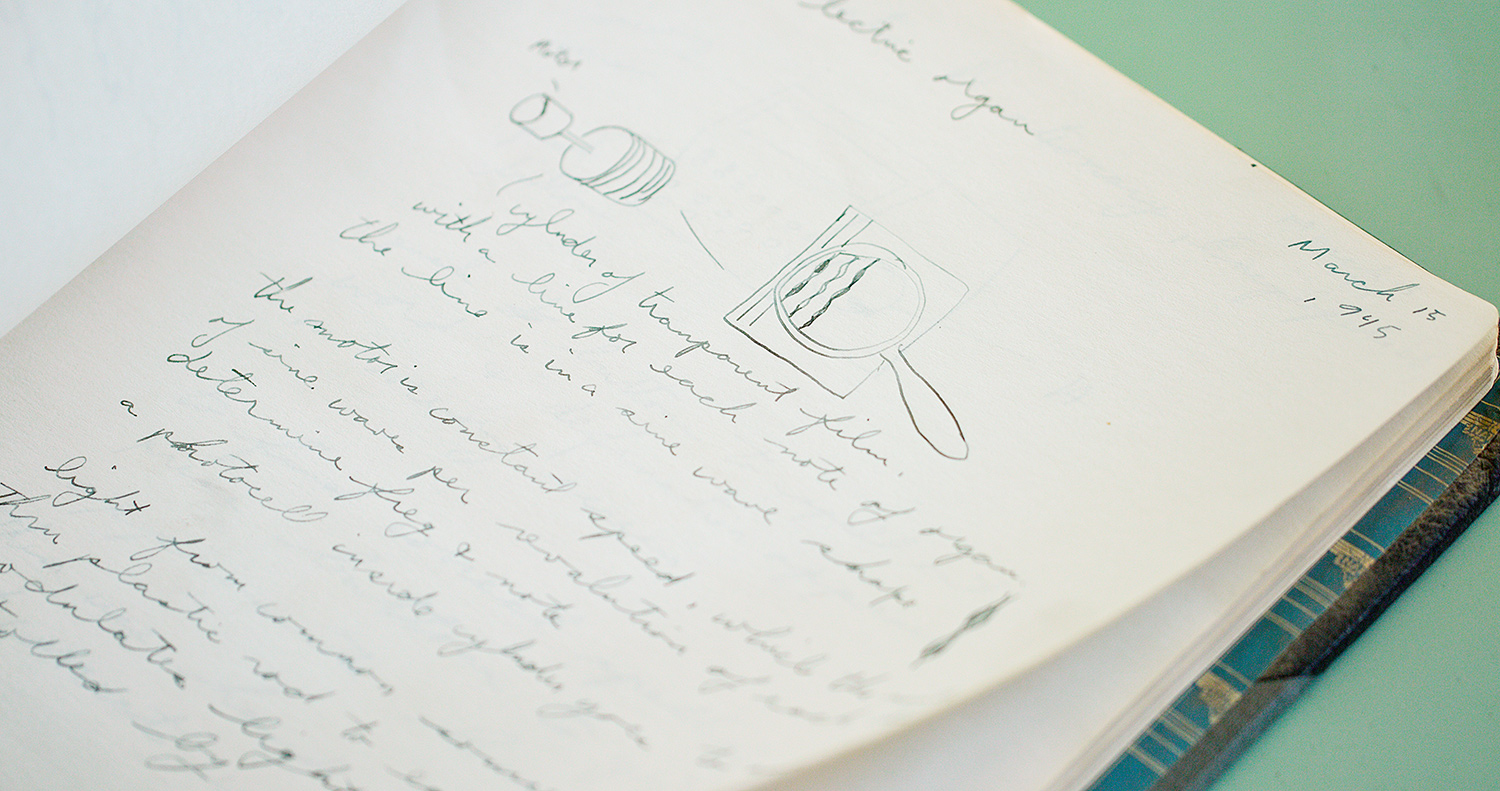

Inventor Eddy Goldfarb's design notebook he used while serving aboard the USS Batfish in World War II. Initially, he created items across multiple industries, but eventually decided to specialize in the toy business.

(Courtesy of the Goldfarb family)

Working in 4-hour on/off shifts, Chief Radio Technician Goldfarb and his crewmate operate the submarine’s radar or sonar equipment, diligently searching for enemy aircraft or ships. The work demands absolute concentration — the lives of the Batfish crew depend on it. Relieved from his watch, an exhausted Goldfarb slides down to the cold, hard floor of the submarine’s attack center to rest until his next watch begins.

His mind, able to disengage from reality momentarily, drifts back to the motors, his notebook, and the creations he dreams to make a reality.

“I’ve always wanted to be an independent inventor,” says 102-year-old Adolph “Eddy” Goldfarb, a toy maker who has created more than 800 mechanical toys, games, dolls, bubble guns, video games, home sports systems, and other items over his nearly 80-year career. Some of his most iconic creations include the Yakity-Yak Talking Teeth, KerPlunk, Stompers, Giant Bubble Gun, Vac-U-Form, and Battling Tops.

Born in 1921 in Chicago to Jewish immigrants from Romania and Poland, Goldfarb said he and his two siblings didn’t have many toys growing up but would use common household items for play. Tinkering and self-learning from a young age, Goldfarb enjoyed activities like taking apart a broken radio his father brought home or reading his brother’s Popular Science magazine cover-to-cover each month.

“My mother once wanted to give me 25 cents a week if I would stop thinking,” he quipped with a wry smile.

Goldfarb credits a dinner guest of his father’s for introducing him to the idea of innovation as a career.

“He introduced him as an inventor and that’s where I learned the word,” he recalled. “[From that moment] I knew I was going to be an inventor when I grew up.”

The Goldfarb family: father, Louis, and mother, Rose, standing behind eldest son Bernard sitting at left, Bernice sitting center, and Eddy standing on the right.

(Courtesy of the Goldfarb family)

Goldfarb spent his early childhood years coming up with various design ideas and sending pitches to multiple manufacturers, only to receive rejection letters — an indication of obstacles to come.

During the Great Depression of the 1920s and 1930s, The Goldfarb family eked out a living on their father Louis’ garment industry income and side hustle of selling goods on a pushcart on Maxwell Street — one of the poorest parts of the city on the Near Westside of Chicago.

Life changed dramatically after Louis died at age 44 in 1933 following a year-long battle with throat cancer. Eddy was just 12 years old.

“That was a big turning point in my life because we all had to go to work,” he said. “We had a hard time after [his passing]… but we got by.”

No longer able to afford the family home, the Goldfarbs were forced to move into the backroom of a candy shop. Eddy, his older brother, Bernard, and his mother, Rose, all took jobs to make ends meet while the youngest, Bernice, took care of the household. Goldfarb spent his teenage years working various jobs like delivering groceries and newspapers and as a soda jerk for Shuster’s Drug Store until his mother remarried and moved to Brooklyn, New York, taking the financial burden off the young man’s shoulders.

“[That] was the first time I was able to keep what I earned and become independent finally,” he said. “When I went out on a date, I was able to spend some money.”

Despite excelling in school, Goldfarb couldn’t afford college tuition. After high school, he got a job as a lab technician with Chicago-based Wheelco Instrument Company, which made electronic switches, indicators, and controllers for industrial and safety equipment.

He submitted an idea to the company that would solve a pesky problem for the precise instrument industry — how to keep the instrument pointers from vibrating. His proven solution earned him a promotion to Wheelco’s research and development department.

Goldfarb’s upward job trajectory was halted by events halfway around the world: the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

He was standing alone in the kitchen of his third-floor apartment in Chicago when the news bulletin blared from the radio’s speakers.

“I was horrified,” he said. “I was very young, but like millions of others, I was thankful that I lived in this country and am patriotic [so I volunteered].”

During his more than 3 years of military service, Eddy Goldfarb received several meritorious conduct commendations and campaign ribbons while serving as a radio technician aboard the USS Batfish, a submarine that saw action in the Pacific theater during World War II. He is believed to be the last surviving member of the World War II Batfish crew.

(Courtesy of the Goldfarb family)

Driven to help after the United States entered World War II following the attack, Goldfarb enlisted in the Navy in 1942. Always interested in physics and electrical engineering, he entered a new Navy radar training program. He was sent to the University of Houston to study electrical engineering and was then sent to a secretive radio material program at Treasure Island, located outside of San Francisco, California. In addition to maintaining and repairing all the electrical equipment onboard a vessel, Goldfarb would also operate the radar and sonar systems.

“Radar was very new, was very hush hush, and I was very interested in that, but I also wanted to see action,” he said.

Goldfarb and two of his friends would see plenty of it after volunteering for submarine duty.

Assigned to the USS Batfish as a radio technician, Goldfarb served in the Pacific theater from 1943-1945, including patrols near Midway, the Marianas, the Palau Islands, Guam, and the South China Sea.

In its seven war patrols, the Batfish is credited with sinking nine Japanese ships, including three Japanese submarines in four days — a feat unsurpassed to this day.

“I would climb down the hatch and not climb up to the surface for at least 60 days,” he wrote of his wartime experience in his 100-word story titled “The Good Old Days.” “No sunny days, no starry skies, and during the worst kinds of stormy weather. Planes bombed us, we were depth-charged hundreds of times, they fired cannons at us, we fought on the surface with machine guns… we were scared but it was worth it. You know why? My shipmates.”

Although radar was a new technology, Japanese aircraft had learned how to avoid detection — something that could have proven deadly for the Batfish crew if not for Goldfarb’s creative solution.

“The Japanese planes came in on us by skimming the water... and our radar would not pick it up,” he said. “So I invented a radar [antenna] to lower the radar [beam] to pick up the low flying planes that came in.”

For his meritorious conduct and ingenuity, Goldfarb received a Letter of Commendation & Ribbon during the Batfish’s first war patrol in enemy waters from December 11, 1943, to January 31, 1944.

Of Goldfarb the Letter reads, in part: “As Radio Technician 1st Class, his exceptional skill and high degree of proficiency at this battle station materially assisted his Commanding Officer in conducting successful attacks which resulted in the sinking of two enemy passenger-freighters totaling 15,680 tons. His coolness and devotion to duty contributed directly to the success for his vessel in evading enemy countermeasures. His conduct throughout was an inspiration to all with whom he served, and in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

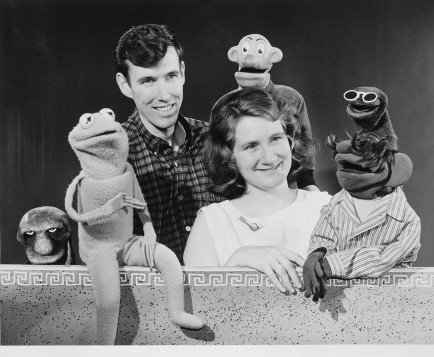

Anita and Eddy at the Copacabana Club in Chicago during their courtship. Married for 65 years, the couple supported each other both personally and professionally.

(Courtesy of the Goldfarb family)

Despite facing constant danger during his service on five war patrols, Goldfarb would use his downtime to think of new inventions, filling notebook after notebook with drawings and written descriptions of inventions varying from miniature organs to rockets and self-landing helicopters.

“I had ideas all over the place and [I wasn’t] getting [any]where,” he said, alluding to the rejection letters from manufacturers he received as a child.

A voracious reader during his time on the Batfish, Goldfarb said he realized he needed to specialize in one industry.

“Since I had no money, I thought I would get into the toy industry,” he said. “I felt that would be the least amount of investment that I would have to make, inventing toys.”

With the war at an end, Goldfarb returned to Chicago after being honorably discharged in December 1945, ready to make his dreams a reality.

One chance encounter would play a vital role in his future success. On a Saturday night, he and a friend went to a veterans dance where they laid eyes on a trio of young ladies in the crowd. Goldfarb zeroed in on the woman in the middle.

“I was sitting when they walked by. I noticed her... it was wow. Not just because she was beautiful, but behind those blue eyes, there was so much more,” he recalled, his eyes softening as he reflects about the day he met his future wife, Anita.

"We danced and when I held her and she wrinkled her nose, that was it. I didn't want to rush her or look like a weirdo, so I waited till the next day to ask her to marry me.”

The pair were married nine months later.

During their courtship, Anita agreed to financially support Eddy so he could devote his time to inventing toys despite reservations from both sides of the family. The newlyweds moved into Anita’s bedroom in her parents’ apartment, and Eddy spent the next few years creating prototypes while Anita worked to support the couple on her secretarial salary.

Not knowing anyone in the toy industry, the Goldfarbs sent out letters to manufacturers, advertising agencies, and anyone else they could think of. Unlike in his youth, one of these letters received a positive response.

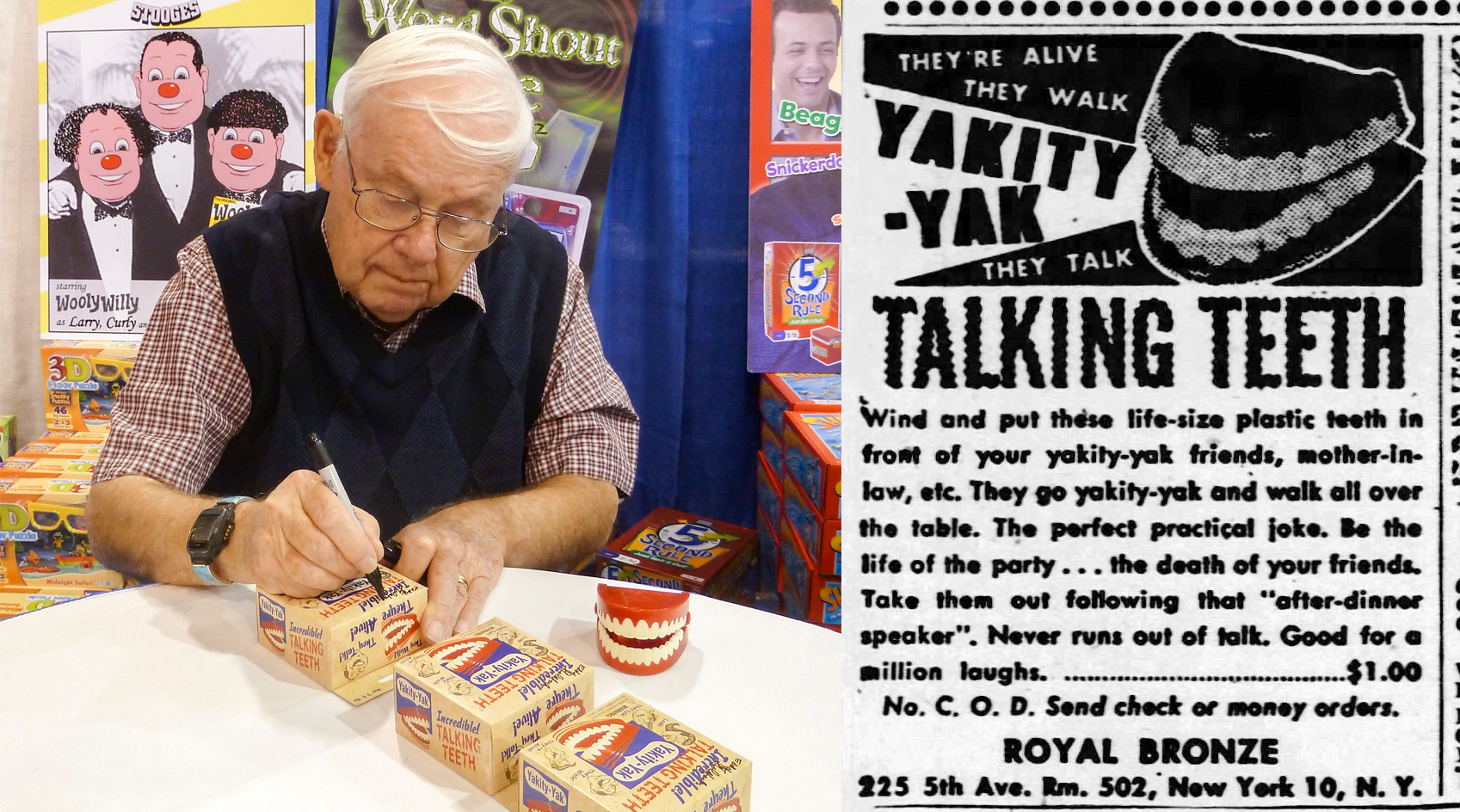

On left, Eddy Goldfarb autographs his famous invention, Yakity-Yak Talking Teeth, while attending the Chicago Toy and Game Fair in 2010. At right, an advertisement from 1949 published in the Daily News newspaper.

(Courtesy of Lyn Goldfarb/ Newspapers.com)

Marvin Glass, a toy promotor and manufacturer based in Chicago, answered Goldfarb’s letter and invited him to share his toy ideas. Goldfarb presented Glass with a set of motorized teeth that would chatter when wound.

The idea for the now iconic Yakity-Yak Talking Teeth — seen in movies like "The Goonies" and "A Christmas Story" — came from a newspaper ad Goldfarb saw for a container for false teeth called the “Tooth Garage.”

“I thought, oh my God, false teeth in a garage. That’s funny. I’m going to make something with false teeth,” he said with a laugh.

After securing a set of false teeth from his dentist to use as a model, Goldfarb made a prototype sitting at the kitchen table of a friend’s home. Using casting, he made everything by hand except for the motor, which he repurposed from another gadget.

Glass took this simple gag item to novelty king Irving Fishlove, who purchased it for $2,500, of which Goldfarb received $900. Although the inventor was able to purchase a new winter coat — a vital necessity for the frigid Chicago winters — he said Glass’s outsized cut of the profits made him regret selling it outright. For the rest of his career, Goldfarb vowed to license, not sell, his creations.

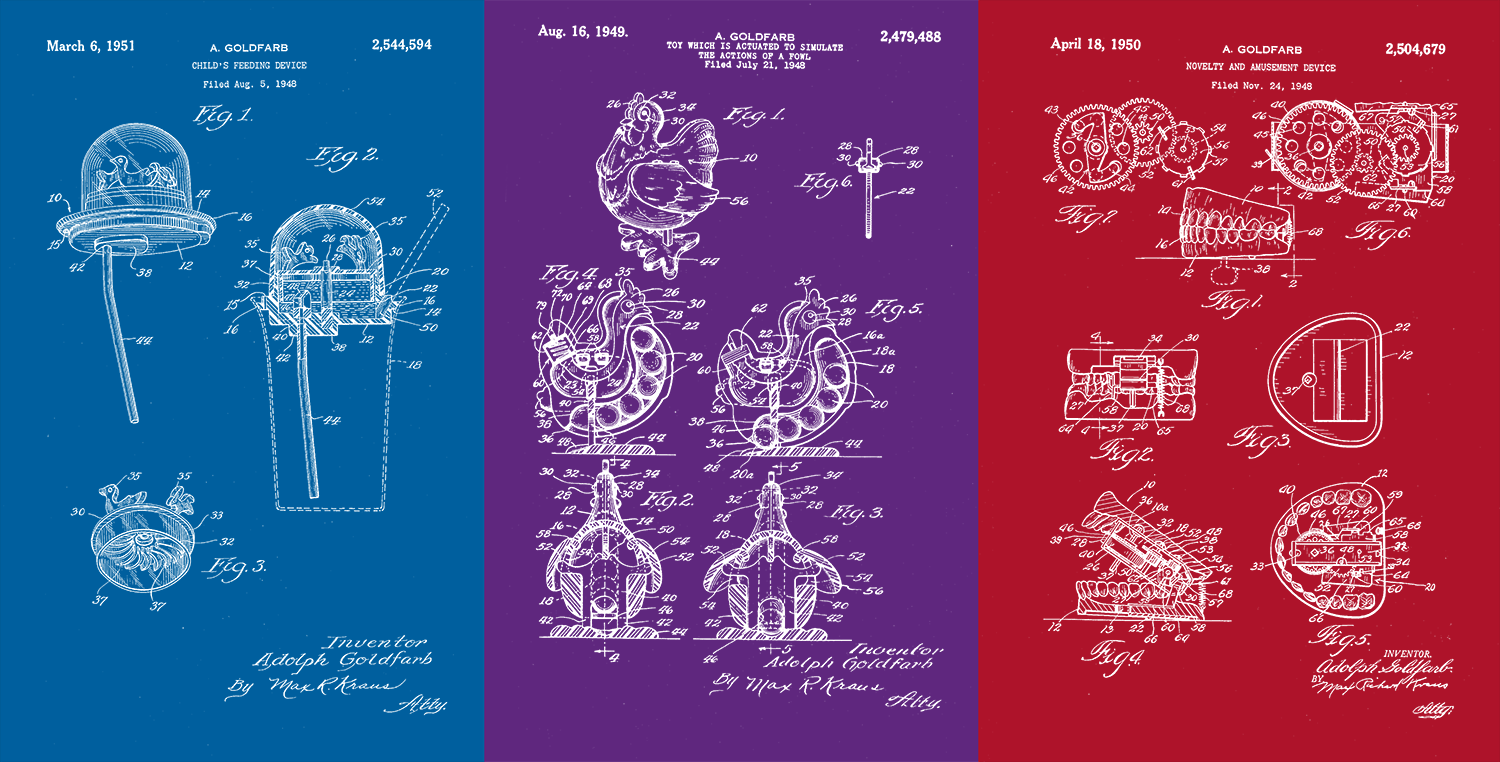

Through that initial industry connection, three of his inventions — Yakity-Yak Talking Teeth, Busy Biddy Chicken, and Merry Go Sip — were showcased at the 1949 Toy Show in New York, the toy industry’s annual expo. The Busy Biddy Chicken was an egg-laying mechanical toy while the Merry Go Sip was a child’s drinking cup. It had a carousel lid top that would spin when a child drank from the attached straw. All three were commercial successes and launched Goldfarb’s career as a toy inventor.

Patent visuals for the Merry Go Sip, a child's drinking cup with a carousel top, the egg-laying Busy Biddy Chicken, and Yakity-Yak Talking Teeth.

(Jeff Isaacs/USPTO)

With this initial achievement and 2-year-old daughter Lyn in tow, the Goldfarb family moved to southern California in 1952, but immediately ran into financial troubles. Goldfarb said Glass, angry about the move out West, refused to send him any royalties for the toys he licensed with him.

Despite the setback, Goldfarb turned his one-car garage into a model shop and continued to create new toy designs, but monetary compensation flowed much slower than new ideas. When Anita and Eddy’s daughter Fran was born in 1953, they couldn’t afford the hospital bill. Desperate for an immediate influx of cash, Goldfarb took an idea for a toy to Lew Glaser of Revell Toys in the middle of the night and sold it to him.

In an era when most new toys were created in-house by company employees, Goldfarb struggled to repeat his early success as an independent toy inventor.

With a growing family to support, he took a leap of faith and booked a one-way ticket back to Chicago to attend a toy show — a last ditch effort to find another big break.

Because he was an inventor and not a toy buyer, he was denied entry. Determined, Goldfarb checked every exterior door to the building until he found one unlocked.

“I found myself behind all the exhibits and it was dark… I saw this one place that looked like a door, and so I pushed [on it] and it didn't swing open, it fell down — it was part of the exhibit of Ideal Toy Company — I rushed right out and left the room. I scared the hell out of them.”

Goldfarb returned to the scene of the calamity, apologized, and was invited by company officials to show them some of his new toy ideas. He would go on to license more than 50 items with Ideal Toy Company over the years, including Snake’s Alive!, Roy Rogers Quick Shooter Hat, and Marblehead among others.

Through creative perseverance, Goldfarb and his new team, A. Eddy Goldfarb & Associates, would find success licensing his creations to household names such as Mattel and Milton Bradley, as well as small start-up toy manufacturers, over the coming decades.

There was the Vac-U-Form, a plastic molding kit, that Goldfarb licensed to Mattel in the early 1960s despite a demonstration hiccup. During a meeting with company co-founder Elliot Handler, the light bulb used in Goldfarb’s prototype burned Handler’s desk — a humorous and humiliating moment for the inventor.

KerPlunk, a game consisting of a plastic tube, small stick-like rods, and marbles, was created by Goldfarb and Rene Soriano and originally marketed by Ideal Toy Company. The rods are inserted into holes in the tube and marbles are placed on top. The objective of the game is to accumulate the fewest number of marbles in a player’s tray while removing the rods. According to Goldfarb’s son and business partner, Martin, the toy has been on the market since its introduction in 1967.

But for every success, he also faced rejection — at least initially.

“I'm a real optimist,” he said of facing constant pushback in his professional life. “I mean, I annoy people, I always have, but it always helped me all through my life.”

One of Goldfarb’s most iconic creations — the bubble gun — almost never came to be.

“I showed it to one toy company after another, starting with Mattel,” he recalled. “And they said, ‘why would anyone spend $3, $4 for a bubble gun when they can buy a bottle of bubble fluid for 39 cents?’”

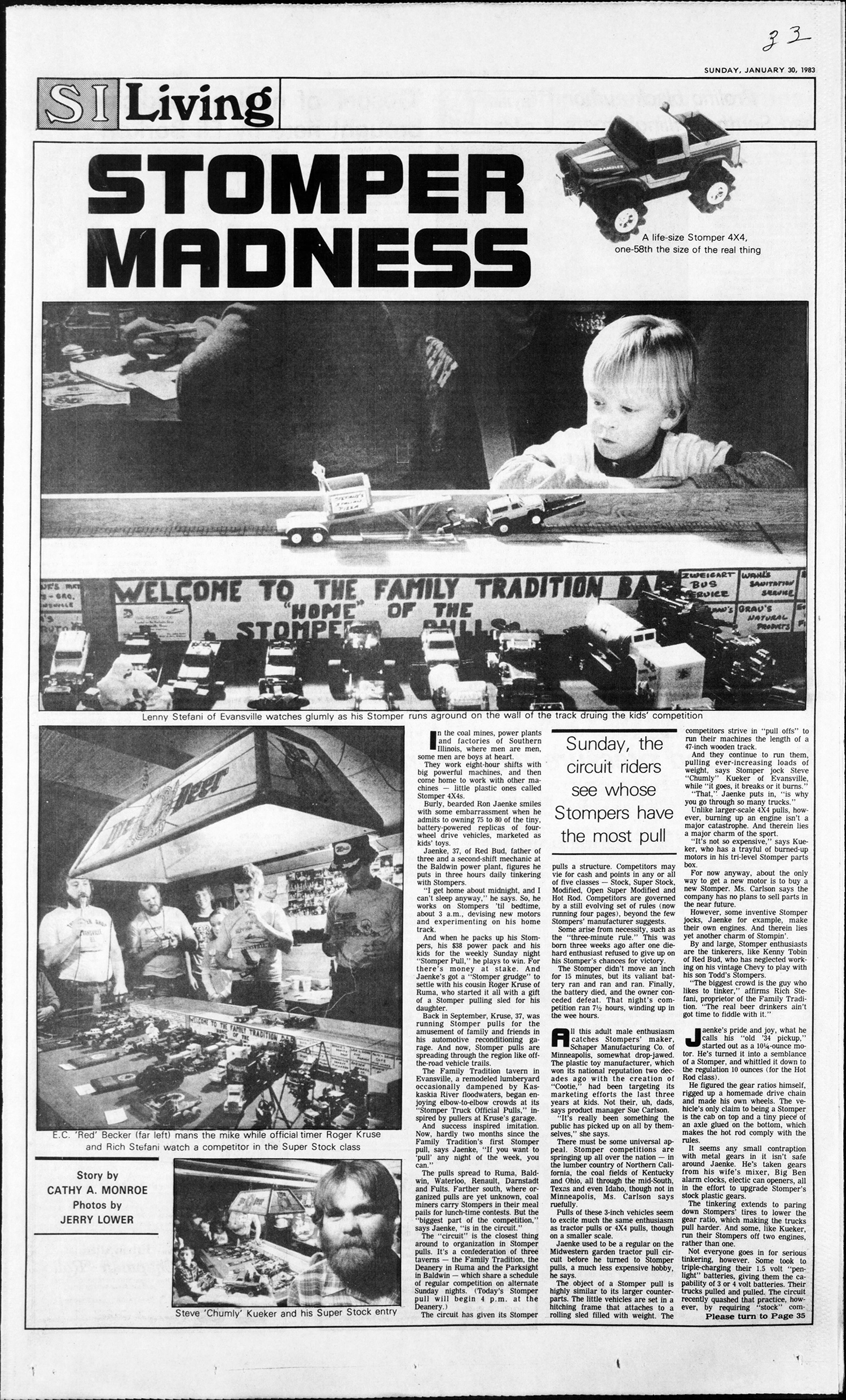

Known for its impressive pulling power, Stompers was an instant commercial success upon its debut in 1980 and was beloved by both young and old vehicle enthusiasts as seen in this full page story from the Southern Illinoisan's January 30, 1983 edition.

(Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

Turned down by every major toy manufacturer at the time, Goldfarb turned to John Osher, a then-budding serial entrepreneur, who had previously found commercial success by licensing the inventor’s Arcade Basketball, a home version of the more expensive arcade system.

Osher initially declined, but was persuaded by his then-girlfriend, Bonnie, to invest in the item.

“She said, ‘John you're going to make this item… and he said, no, I'm not. And she said, yes, you are.’ And before the meeting was over, he said he'll invest the money and make it,” Goldfarb recalled with a laugh. “And at the toy show, he called me and said, ‘we have a huge success on our [hands].’”

In addition to being a popular childhood toy, the bubble gun today is also used as a tool in some pediatric autism screening methods.

Another of Goldfarb’s inventions, Stompers, also faced early obstacles.

The company that initially licensed the motorized truck and track set quickly returned it. Goldfarb said the toy sat in the closet for a time until an official from a small toy company, Schaper Toys, approached the inventor looking for a product that would help them avoid bankruptcy.

“He came to me and told me [the company] had no money. [They] had no [research] and [development] staff, but he needed a product, and he needed engineering help,” he recalled.

Goldfarb took the truck and track set out of the closet, showed it to the Schaper official, and offered his team’s design and engineering expertise as part of the licensing agreement. It was a deal.

Under the creative direction of Goldfarb and lead designer Del Everitt, Stompers became an enormous commercial success with millions of units sold and is a prized collectible today.

At its height, the inventor’s company employed 39 workers and owned three buildings. His employees included designers, model makers, sculptors, and engineers. A family affair, Anita took an active role in the company assisting with administrative duties as well as creating new items.

“I talked over every idea I had [with her],” Goldfarb said. “She and I came up with games together where we both worked on [them], and [other times] she worked on games [alone].”

Some of the couple's joint efforts include Number’s Up, an electronic timed number ordering game, and on a simple preschool assembly toy vehicle and driver.

Not to be left out, the couple’s three children Lyn, Fran, and Martin, served as research subjects.

“We were sworn to secrecy when he brought toys home for us to test out. We were never allowed to share them with anybody until they came out. And he had a locked room, which none of us were allowed in. That was where he did [some of] his inventing work,” said his eldest daughter, Lyn.

Goldfarb quipped that his children played with some of the most expensive toys to never see daylight.

A giant in the toy industry, Goldfarb was inducted into the Toy Industry Hall of Fame in 2003 and was later given a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Chicago Toy and Game Group in 2010. Across the ocean, he became the first American recipient of the International Designer and Inventor of Toys award at the London Toy Fair.

Anita and Eddy Goldfarb with their kids during the 1970s. The children from left: Fran, Martin, and Lyn Goldfarb.

(Courtesy of the Goldfarb family)

Despite holding nearly 300 patents and being the creator of more than 800 items, Goldfarb points to his three children, two grandchildren, and the impact his creations have had on millions of other children as his true legacy — one built through partnership with his beloved wife of 65 years, Anita, who passed away from Parkinson’s Disease in 2013.

“She was someone who was very, very interested in being a mother, very invested in being a partner, but also in being a person in her own right,” said daughter Fran of Anita, who obtained two degrees, wrote children’s stories, hosted foreign dignitaries through her work with UNICEF, and taught college courses all while assisting her husband in the family business.

The Goldfarb children said witnessing their parents’ work ethic and creativity made a lasting impression.

“My dad could look at a brick wall and get an idea for a toy,” Fran said, only half joking. “He just trained himself to think that way.”

Each of the Goldfarb children has honed that creative spirit in their own professional lives. Lyn is an Oscar-nominated and award-winning documentary filmmaker whose most recent project “Eddy’s World” chronicles her father’s career and is being shown on PBS; Martin teamed up with his father in 1998 to form a new partnership, Eddy & Martin Goldfarb and Associates, which continues to invent new toys and games including Shark Attack; Fran is a retired health educator who focused on neurodevelopment and related disabilities.

A family man at his core, Goldfarb sees that real success isn’t found in the sales figures.

“When one of our games sold a million units... we knew that a million families were together playing that game,” he said, adding his inventions are all about “the education of kids and [bringing] families together.”

Calling the toy market a “noble industry” Goldfarb said children playing with his toys use their creativity, imagination, social skills, and are introduced to engineering and other STEM concepts while also bonding with family and friends.

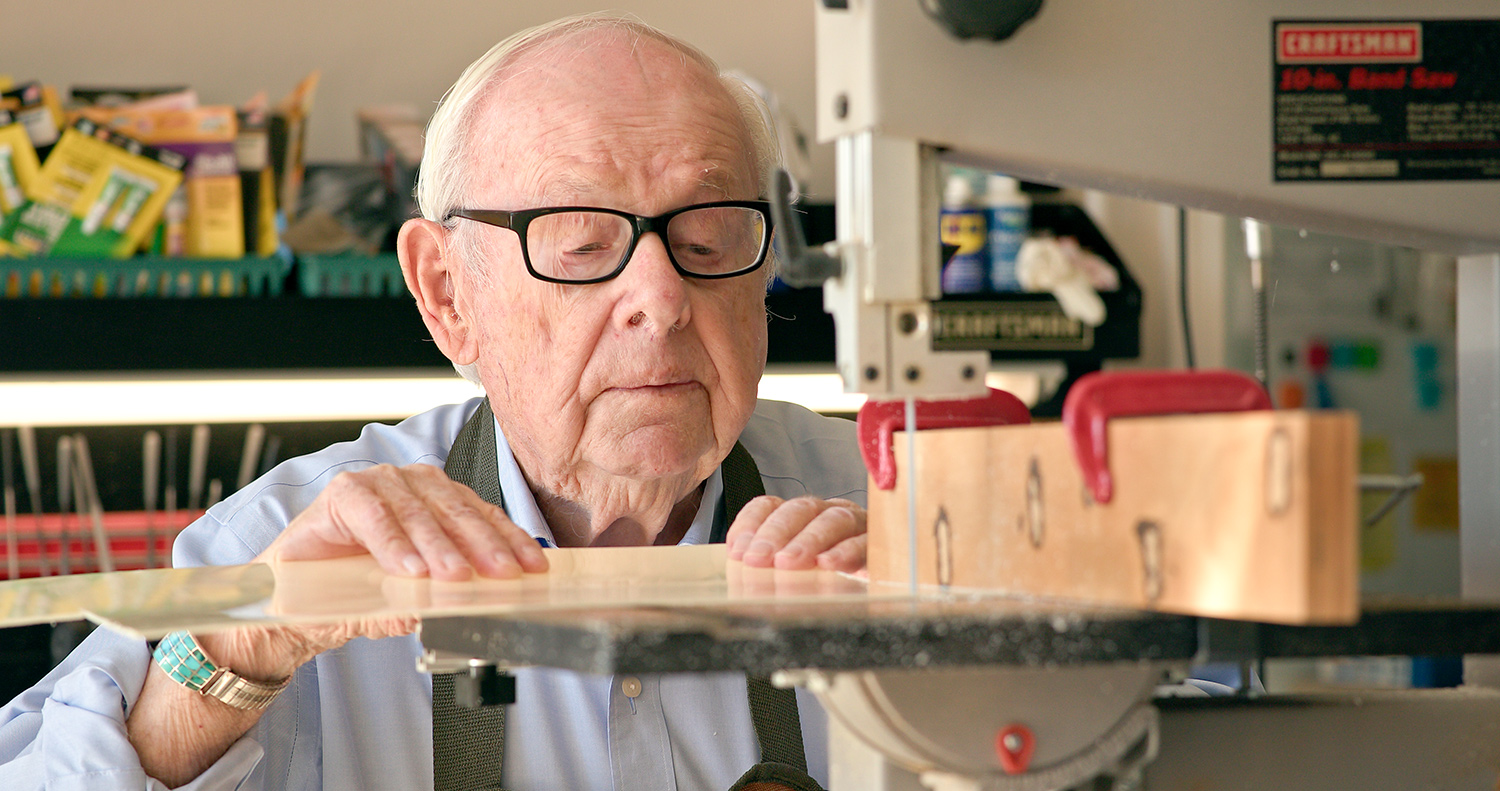

Eddy Goldfarb continues to create new inventions in his hobby shop, located in his retirement community in California. He also creates 3D-printed artworks and writes 100-word stories.

(Courtesy of Eddy's World)

Even at 102 years old, he continues to create.

Goldfarb crafts new items by hand in his workshop, located in his retirement community, and writes 100-word fiction and nonfiction stories, a hobby he picked up after seeing an ad for a writing contest in his local newspaper more than two decades ago. His stories were recently published in a book titled “It’s Going to be a Big Day: 101 100-word Stories by a 101-year-old.” Goldfarb also creates his own lithophane photographs, translucent photos that use natural light to show details, on his 3D printer. He and his son, Martin, even received a patent in 2001 for an “apparatus and method for... creating a thin lithophane-like pictorial work.”

Goldfarb credits his longevity to a combination of genes, positivity, and activity.

“I inherited some good genes... but I really think being creative helps,” he said. “It stimulates your brain and I think that helps your body.”

He mentioned that a female resident of his retirement community lived to be 107 years old, a record at the facility. Ever the optimist, his answer to the question of if he plans to beat that record was simple: “Oh, without a doubt.”

Credits

Produced by the USPTO’s Office of the Chief Communications Officer. For feedback or questions, please contact inventorstories@uspto.gov.

Story by Whitney Pandil-Eaton. Contributions by Rebekah Oakes, David Kadas, and Eric Atkisson. Special thanks to Eddy, Lyn, Fran, and Martin Goldfarb, James Erb, Mark Allen, and the National Archives and Records Administration. Image of Eddy Goldfarb with a bubble gun in the beginning of the story is courtesy of Eddy's World.

References

“Awards: Submarine and Crew,” USS Batfish (SS310) http://www.ussbatfish.com/awards.html

“Batfish I (SS-310),” Naval History and Heritage Command. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/b/…;

Cutler, Irving. The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb. 1996.

“Eddy’s Story,” Eddy’s World: A documentary short about toys, ideas, and aging. Accessed October 10, 2023. https://eddysworld.net/eddys-biography/

Erb, James. Curator, War Memorial Park. Interview with Whitney Pandil-Eaton. November 1, 2023.

Gold, L. “A Life’s Story: The Joyful Inventor,” Apple Podcasts. Accessed October 18, 2023. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-joyful-inventor/id1565179566?i=1000530123803

Goldfarb, Adolph. Notice of Separation from U.S. Naval Service. National Personnel Records Center. National Archives and Records Administration. Received October 30, 2023.

Goldfarb, Eddy; Goldfarb, Fran; Goldfarb, Lyn; Goldfarb, Martin. Interview by Whitney Pandil-Eaton, October 25, 2023.

Harris, R., “Playing With Toys Keeps This 99-Year-Old Inventor Young,” Next Avenue. February 10, 2021. https://www.nextavenue.org/playing-with-toys-keeps-this-99-year-old-inventor-young/

Kisken, T. “Thousand Oaks inventor who produced talking teeth, 800 other toys still working at 100,” Ventura County Star, December 23, 2021. https://www.vcstar.com/story/news/local/2021/12/23/legendary-inventor-kerplunk-yakity-yak-wind-up-teeth-800-other-baby-boomer-toys-works-age-100/8918832002/

Langsworthy, B., “Legendary inventor Eddy Goldfarb – the man behind toys like Chattering Teeth, Stompers and KerPlunk – on the power of optimism,” Mojo Nation. March 28, 2023.

“Naval Legends: USS Batfish,” World of Warships. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=86W66hi1TfU

Setteducati, M. “Eddy and Lyn Goldfarb,” G4G Celebration. October 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dw6IzKwp8V0

War Memorial Park/USS Batfish, City of Muskogee, OK., Accessed October 15, 2023. https://www.muskogeeonline.org/visitors/attractions/war_memorial_park_uss_batfish.php