Cultivating community-driven change: Olin Kealoha Lagon

After enduring a violent and poverty-stricken childhood, serial social entrepreneur and Native Hawaiian Olin Kealoha Lagon oscillates between creating patented new technology and conducting philanthropic work to improve the standard of living for Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders in Hawaii.

23 min read

Each month, our Journeys of Innovation series tells the stories of inventors or entrepreneurs who have made a positive difference in the world. This month, Whitney Pandil-Eaton's story focuses on serial social entrepreneur Olin Kealoha Lagon who, after a tragedy-filled childhood, has committed to uplifting the Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander community through his energy-saving business and his philanthropic activities. After reading, take a deeper dive by watching Jay Premack's mini-documentary film about Lagon and hear him describe his innovation journey in his own words.

Do you know an innovator or entrepreneur with an interesting story?

Olin Kealoha Lagon inspects his newest crop of taro at his family's plot.

(Whitney Pandil-Eaton/USPTO)

His hands, calloused like a craftsman, gently grip the broad green taro leaves, and a single bead of sweat trickles down his youthful face as he turns the leaves to inspect their growth in the 75-degree spring midday sun. Like his ancestors did centuries ago, Olin Kealoha Lagon uses traditional aquaculture techniques to grow taro, a food staple of Hawaii that has nourished his people for more than 1,500 years. The volcanic soil, fertile makai (oceanside) flats, and freshwater streams from the Ko’olau Mountain range supplies the plants with the nourishment necessary to grow tall and dense on the small plot Lagon’s ancestors have farmed for hundreds of years.

Taro, a versatile root vegetable known as kalo in the Hawaiian language, is deeply ingrained in Hawaiian culture. So much so that it is rooted in the family naming structure.

According to oral tradition, Wākea, the sky father, and Ho’ohokukalani, who made the stars, wanted to have a child. When their first child was stillborn, they buried the body near their home. From this burial plot grew a taro plant they named Haloanaka, loosely translated as “long stock trembling.” The couple’s second child was a human boy named Haloa, from whom Native Hawaiian people are descended.

“I’m part of this 800-year-old journey of Hawaiian people eating, preparing, and growing a plant that has no flowers or seeds. Storms, hurricanes, fires, pandemics, wars over the last 800 years could have easily stopped this from happening, but it didn’t. We take care of the land that takes care of us.”

Dilynn-Jae Maglinti, left, and Michael Kaaialii, right, work together to harvest taro.

(Whitney Pandil-Eaton/USPTO)

In an adjacent plot, another Native Hawaiian family gathers for the daylong process of harvesting taro that will be used to feed 400 guests at an upcoming traditional Native Hawaiian wedding.

Austin Maglinti, the groom-to-be, wades silently in the cool, hip-deep waters, making his way through the lo’i kalo (the wetland taro fields) just like his ancient Polynesian ancestors from islands throughout the central and southern Pacific Ocean did. Swimming below the surface are ‘o’opu (goby fish) while above the surface the endangered Gallinule – a black bird with a red head who according to tradition gave fire to the Hawaiian people – flies on the soft ocean breeze.

His bride-to-be, Dilynn-Jae, and others work in concert loosening the plants from their muddy base and preparing them for the journey ahead. In addition to the taro, the couple also recently butchered an 800-pound pig for the feast.

In aquaculture cultivation – dating back 800 years in Hawaii – farmers plant the taro then flood the land by diverting water from the nearby rivers that flow down the mountainside. Similar to rice paddies, the water makes weeding unnecessary – an early Polynesian innovation.

Intent and interconnectedness are central to the success of the taro plant and the Hawaiian people. Seedless, the taro plant relies on farmers to cut and rebury bits of the roots to continue propagation. Each taro plot is connected by a small channel that then feeds into the neighboring plot, meaning success is dependent on the knowledge and care of neighbors. This connectivity is known as Mālama ʻāina in Hawaiian.

It is here at the base of an extinct shield volcano on O’ahu where the seemingly disparate ideas of futuristic technology and ancient practices collide.

Explaining that the technique of cultivating taro involves speeding up, slowing down, and storing water is similar to how resistors and capacitors function in electrical circuits, Lagon said:

“The taro fields represent a circuit board, which runs modern society... so when we learn about circuit boards it’s very familiar to us [because] we do that, but we do that with water.”

He builds off the ancestral knowledge of the past to tackle the problems of today.

“Almost all of my inventions, innovations come from this collision of different spaces,” said Lagon, a serial social entrepreneur named on nine patents that span multiple industries, with three more provisional patents in progress. He describes social entrepreneurship as using innovation and business to address socioeconomic inequalities.

He was a pioneer in crowdfunding technology with ChipIn, a company he co-founded in 2006 that generated $100 million in little more than two years with the company. He created large-scale software programs used by companies like Nike, Disney, the Olympics, MIT, and FedEx. Currently, he is transforming the energy sector with his use of machine-learning technology to increase energy efficiency in household appliances and reduce the strain on the overall power grid.

How has Lagon created industry-changing technology in so many different sectors?

By keeping his brain “unwired.”

Lagon is an avid reader and lifelong learner. For the last 20 years, he has routinely taken two to three classes annually on diverse topics such as Hawaiian chanting and language, cloud technology and machine-learning, slack key guitar lessons, and Greek memory classes, a technique that puts memories into places. Recently, he learned how to file a provisional patent application himself using resources from the United States Patent and Trademark Office website. With the goal of applying for 20 provisional patent applications this year, he is now teaching his colleagues how to write patent applications.

“Innovation is nothing more than two really different things colliding together… when your brain starts to learn these different things, I think worlds collide.”

A plumbing contractor working with Hawaii-based Shifted Energy installs copper water lines as part of the installation of a new electric water heater. The appliance is equipped with the company's machine-learning technology which increases energy efficiency.

(Jay Premack/USPTO)

His idea for crowdsourcing software? It came from a familiar office occurrence. After Lagon’s oldest son, Noah, was born, his colleagues sent around a congratulations card and took gift card donations, but he got the card late due to logistical issues and an inefficient process.

The idea for Lagon’s most recent business, an energy company that focuses on optimizing home appliance energy usage, came after he hit a roadblock and reached out to an unlikely source for help.

“I went to Reddit and asked some questions,” he said. “I connected with a guy from Macon, Georgia, who had a [general purpose] circuit, so I bought that and used over-the-counter parts to make [the prototypes], recruited 20 families, installed 20 units - they worked.”

Lagon, along with other community leaders, is using this unique approach to address myriad issues that have plagued Native Hawaiian communities since the island was forcibly annexed by the United States in 1898.

His motivation in business and in life is simple: He wants to raise Native Hawaiian standards of living and enable the islands to become 100 percent sustainable.

Located in downtown Honolulu, Hawaii, Kuhio Park Terrace (KPT) is the largest public housing block in the state. The complex, now privatized public housing, had a long history of health and safety violations during the time Lagon and his family lived there in the 1970s and 1980s. Although he faced violence and injustices, Lagon said his childhood experiences made him stronger. A mural of his mother, Evelyn, was painted on one of the buildings to honor her commitment to the community.

(Jay Premack/USPTO)

In almost every measurable health and socioeconomic metric, Native Hawaiians fare worse than other minority groups.

A 2019 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services report noted that “in comparison to other ethnic groups, Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders have higher rates of smoking, alcohol consumption, and obesity. This group also has less access to cancer prevention and control programs.”

According to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, “the tuberculosis rate in 2019 was 37 times higher for Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders,” than other ethnic groups.

This group also faces tough socioeconomic odds.

Federal data from 2019 shows that nearly 15 percent of Native Hawaiians live at the poverty line, and the unemployment rate at that time was just shy of 6 percent. In the state with the highest cost of living, Native Hawaiians had the lowest median household income of the five largest race groups in Hawaii according to a 2018 state report. Although Native Hawaiians make up only 10 percent of the population in O’ahu, the group accounts for 35 percent of the nearly 4,000 homeless people living on the island. They also make up approximately 40 percent of the prison population in Hawaii.

Lagon has lived some of those statistics.

The youngest of four children and the only boy, Lagon grew up in Kuhio Park Terrace (KPT), the largest public housing block in Honolulu and the last remaining high-rise public housing project west of the Rocky Mountains. Consisting of two high-rise and approximately 20 low-rise buildings, the complex has had a long history of health and safety violations such as gas leaks, broken plumbing, lack of hot water, and inoperable elevators, causing accessibility issues for residents with physical limitations. The complex is now privatized public housing and has undergone renovations to address some of these issues.

Outside of homelessness, Lagon said residents of KPT were the lowest-income demographic in Hawaii. The high-rises, located in northwest Honolulu, are surrounded by businesses and multimillion-dollar homes.

Lagon, who lived in a two-story, six-unit housing project at KPT, said being surrounded by immense wealth that was out of reach had a deep impact on his self-esteem and self-worth when he was young. Those feelings were reinforced at school when he would overhear classmates discuss extravagant summer trips when his family could not afford to eat at a restaurant.

“Every day, all these messages were telling me I was less than. Being constantly reminded about this class delta was really difficult and embarrassing because it was not what everyone else was going through.”

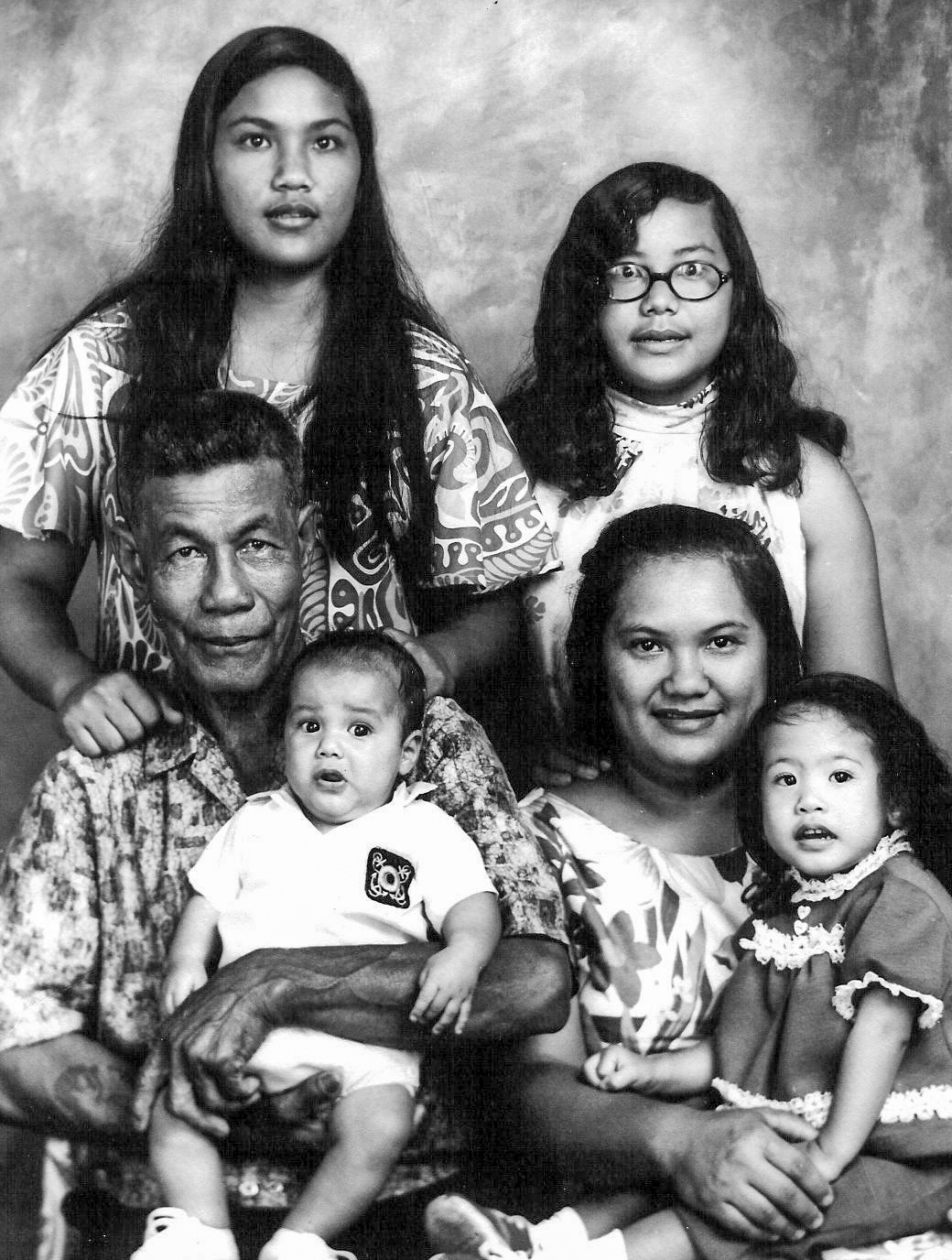

Maximo Lagon and Evelyn Kamakau, center, with their children.

(Courtesy of Olin Kealoha Lagon)

His mother, Evelyn Kamakau, struggled to support her family due to her lack of education. Illiterate and a sixth-grade dropout, she eventually secured employment in the fast-food industry, but money was always tight.

“I remember I stole $5 from my mom to buy some baggy pants. She only had $6 in her wallet,” Lagon said. “She asked me about it later and I realized that was a lot of money to us. I never stole again.”

In addition to financial insecurity, death and violence plagued Lagon’s childhood.

His father, Maximo Lagon, died when Olin was 6 years old. Joseph Donald Peters, his biological father, died when Olin was 14.

“I didn’t really have a father figure growing up, so it was my mom and three sisters,” he said. “In some ways, I still have that void in my life.”

Death struck a third time when Lagon’s best friend, Shannon, was run over and killed by a car as a teenager.

John “Prime” Hina, a local artist and community activist who also spent some of his childhood living in KPT, said violence, gang activity, substance abuse, domestic violence, and suicide were common elements to life there.

“I was 6 or 7 years old when I saw my first jumper,” he said. “You’re at the playground and you hear this loud thump, and everyone scatters.”

Lagon experienced violence firsthand while living at KPT.

Olin Kealoha Lagon takes a moment to reflect after describing in detail how he was stabbed as a child while playing with chalk on the sidewalk near his home at KPT, the largest public housing complex in Honolulu, Hawaii. Despite the violent encounter, Lagon said there were also positive memories of the local community coming together to assist each other when needed.

(Whitney Pandil-Eaton/USPTO)

The then 7-year-old was drawing with chalk outside of his house one afternoon when he was stabbed in the head by neighborhood kids, resulting in a bloody gash.

“My entire side was just full of blood...[but] what happened after is what still haunts me today,” he said. “I needed to go to the ER, but my mom didn’t call 911. My mom called our pastor to take me to the hospital. Years later she told me that with great difficulty, she called our pastor because she needed care too.”

Even at school, violence found Lagon.

“I remember my first high school, ninth grade, the second day I showed up to school I had a gun pulled on me,” he said. “The third day – I was on free lunch – I picked up my free lunch and then some guy came and grabbed my lunch and ate my lunch. And I was really hungry that day.”

Retracing his childhood steps at KPT recently, Lagon reminisced about the bad – being accosted by gang members and a murder committed by a member of the family that lived in his public housing building – but also the good times when the community rallied together during a hurricane or how, despite being incredibly poor, each home in the housing project would give out candy on Halloween.

Olin Kealoha Lagon places his hand on his mother's mural at Kuhio Park Terrace public housing.

(Whitney Pandil-Eaton/USPTO)

But the memories he clings to most are those of his mother, whose mural is displayed prominently at KPT. Her portrait was chosen to represent a Kūpuna (honored elder) in the community when the giant mural was painted by local artists with the assistance of a group of children in 2018. The artist, Prime, said stories of her activism in the community were still shared years after her passing in 2015.

Lagon rests his hand on his mother’s cheek in silence. Tears form but do not fall.

Memories of helping her transform the small section of grass in front of their house into a mini floral paradise. The way she interacted with neighbors. The sparkle in her eyes.

Evelyn’s simple lifestyle and sense of community greatly influenced her son’s work and life.

“She lived a spartan life. She never drove [a car], never bought anything electronic, she ate simple foods,” Lagon said. “She knew everyone by name – she wrote them down in a book – and had us volunteering every weekend, giving back to the community.”

Lagon has taken those lessons of sustainability and community to heart.

He has a zero-energy home, drives an electric car, and has been composting for the last 35 years. Lagon is doing his part to support the state’s transition to 100 percent renewable energy – mandated by a 2015 law – but he is also using his latest innovation to help low-income residents become involved in the renewable energy drive and lower their energy bills, which are nearly triple the U.S. average.

“We knew this transition [to clean energy] was going to leave some communities behind. How do we get renters, low-income folks, people who live in apartments involved?”

Sitting outside her home, Gloria Needs, left, reminisces with Shifted Energy founder Olin Kealoha Lagon about people and events in Waimānalo, Lagon's hometown.

(Jay Premack/USPTO)

The answer is Shifted Energy, Lagon’s latest endeavor that uses advanced machine learning to optimize energy efficiency in water heaters, one of the largest power draws in homes in tropical climates.

Jennifer Ignacio, senior director of project delivery at Shifted Energy, said many residents were months behind on their electricity bills because they were so high.

“These people were severely impacted by Covid because a lot of these folks are in the service industry,” she said. “Then energy prices shot up and many just can’t catch up.”

On the eastern end of O’ahu in the small community of Waimānalo, Gloria Needs, 76, sits outside the home her husband, a shipwright who worked at Pearl Harbor, helped build. Since he passed in 2018, Needs has had to rent out rooms in her home in order to afford her electric bill, which routinely runs more than $1,200 per month.

“At one point I had to cash in one of my annuities just to make my bills,” she said. “I’m retired so I’m always looking for programs to help lessen my costs.”

Technicians from Shifted Energy were at Needs’ home to install a new 65-gallon water heater that is equipped with a cellular-connected control box that can manipulate the water heater’s circuits. The controls allow the company to turn the water heaters on and off to help stabilize the energy grid, acting like a “virtual power plant.” The company uses algorithms to predict how much electricity a family will need for hot water and can program a water heater to absorb excess solar power remotely as needed. The technology is so advanced, it can forecast electricity needs for water heaters in 15-minute increments up to a week in advance.

“We’re solving some really modern problems with [these] innovations in some of the hardest hit communities,” Lagon said, referring to his company’s commitment to prioritize installation in low-income areas on the island.

A recent study found that Shifted Energy’s water heater technology reduced electricity usage by up to 86 percent, saving residents hundreds of dollars. The technology can also be applied to other household appliances, home batteries, and electric-vehicle chargers. Currently, Shifted Energy operates in eight states, Canada, and Australia.

“We get weekly thank yous. It never gets old when you invent something that helps people.”

School-age children are learning to code using the popular "Minecraft" online game.

(Courtesy of Purple Mai'a)

Helping people is what he is all about. As a teenager, he made a commitment to spend half of his adult life participating in philanthropic work. Since then he has served in the Peace Corps and on numerous economic, health, and environmental boards, but his biggest accomplishment to date is Purple Mai’a, a nonprofit he co-founded in 2013.

Nestled between high-rise buildings off a busy street is an industrial yet modern tech hub that is changing the trajectory of young Native Hawaiian lives.

What began as a mission to teach kids how to code has transformed over the last decade into a series of programs for children and adults that aims to inspire and educate the next generation of culturally grounded, community-serving technology innovators.

“When we launched Purple Maiʻa, only three public high schools across the state offered second-year or greater computer science courses,” Lagon said. Today, the program “has grown into the state’s largest Hawaiian-values STEM organization.”

Participants in Purple Mai'a's Humu Pe'a (Hawaiian sailmaking) class are working together to build a canoe prototype out of PVC materials. The nonprofit offers numerous culturally-grounded STEM programs for school-age children.

(Courtesy of Purple Mai'a)

The organization incorporates S.T.R.Ē.Ā.M (Science, Technology, Research, Engineering, Entrepreneurship, Art, 'Āina, and Math) into all its programming. 'Āina translates to “land” in English but has a much deeper meaning in the Hawaiian language that focuses on the reciprocal relationship between humans and the land.

Bringing a holistic approach to the tech space is one of Purple Mai’a’s objectives.

“Our Hawaiian culture is not ancient culture, it’s a modern culture, so what do we bring to the table? We bring a value system, ancestral knowledge built over generations, and we bring that to the tech space that is in need of values and in need of this kind of thinking. We connect the two,” said Mike Sarmiento, vice president of education design at Purple Mai’a. “I don’t have to choose to be Hawaiian like this or like that; we don’t have that conflict. I’m a Hawaiian of today. I use all of these [ancient and modern] tools.”

Thousands of school-age children and adults have participated in both in-person and virtual programs ranging from coding and entrepreneurship classes to business accelerator courses and workforce development.

The courses are providing extrinsic and intrinsic value to participants.

Lagon said adult graduates of Purple Mai’a’s 12-week technology program start with an average salary of $72,500, nearly $20,000 higher than the 10-year average for graduates of the University of Hawaii. On the youth side, two brothers who took several courses went on to form their own T-shirt business, Red Rooster Designs, Sarmiento said. Another program alum is currently a junior at the University of Southern California pursuing a career in computer science.

Reconnecting with their heritage and with each other is equally important, Simiento added.

“It’s very important to start with values first as opposed to the mechanics of building a website or the mechanics of building a business. Those things can be learned. We are in the business of building good people, then we give them the tools to be successful in tech innovation and give back to the community.”

Hidden, multilayered meanings in names are a long-held tradition in Hawaii, and the name Purple Mai’a is no different. Like most things in Hawaii, beliefs of the past are brought forward and reinvented in the present. The organization is named in honor of the banana (Mai’a) tree which holds cultural significance – it also blooms purple flowers.

In ancient times, Lagon said there were certain banana varieties that only men could eat while another variety – a purple banana – was reserved for women to eat.

“Right now, tech space is dominated by men, but we wanted to recognize that women could and should be involved too,” he said.

While acknowledging tradition, Lagon said the organization’s meaning is also about changing how kids are taught in school today from standards-based to passion-based learning.

“Purple is one of the rarest colors in nature, it takes a lot of chemistry to make it,” Lagon said. “If a teacher is mindful to find the purpleness in kids, it becomes the teacher’s responsibility to find the student’s purple.”

The efforts seem to be paying off.

Olin Lagon talks with a high school student about a career in technology during an event at Kamehamena Schools in Honolulu, the largest private school in the world and one that integrates Native Hawaiian culture into its curriculum.

(Whitney Pandil-Eaton/USPTO)

Lagon recently volunteered to speak with high school students interested in tech careers at Kamehamena Schools in Honolulu, the largest private school in the world and one that integrates Native Hawaiian culture into its curriculum.

Senior Kawika Naweli said meeting successful Native Hawaiians in tech is helping to change the narrative at home. Growing up on a Hawaiian homestead – a community that requires people to have 50 percent Native Hawaiian blood – Naweli said more kids are looking into careers in technology instead of following their ancestors into low paying, blue-collar jobs.

“Every one of my neighbor’s’ dads works in construction. That’s not a job that will give you the best opportunities,” he said. Becoming a software engineer will “give me the opportunity to break out of that cycle and change the culture.”

Jade Hao, also a senior, will be pursuing a computer science degree at the University of San Francisco this fall. She hopes to one day become a computational biologist.

“In Hawaii there’s a lot of invasive and endangered species, so I want to be able to help the community that I live in and make sure [Hawaii] is the same for the next generation as it was for me,” she said.

When talking to young people about innovation, Lagon urges them to start a business and volunteer.

Olin's mother, Evelyn, inspired her son to adopt a life of sustainability and community activism.

(Courtesy of Olin Kealoha Lagon)

“You don’t have to wait until you’re wealthy to give back,” he said. “It doesn’t cost you anything to change lives.”

Lagon routinely volunteers to serve food at homeless shelters, organizes trash collection events at the beach, and even cleans school dormitories.

He said his actions are inspired by how his mother lived her life.

Lacking an English equivalent, the word kuleana describes both a right and a responsibility that cannot be disentangled. Using land as an example, Lagon said a farmer would have a right to access the field, but he would also have a responsibility to the land to keep it healthy. Roughly translated as “to do good to/for all,” “Pono” means to live life in a positive way even when no one is looking.

Like mother, like son. Lagon greets every person, regardless of wealth or station, with a warm smile, humble demeanor and thoughtful conversation. Despite the enormous loss and episodes of violence he has endured throughout his life, Lagon makes himself vulnerable and open to connection in order to build a larger, more inclusive community.

“Compassion is the secret to life, I think. If you can’t be vulnerable and compassionate, then it's hard to be connected with other people.”

Ikaika Bishop, in the water, and Zachary Pillen, on the bridge, install a water level senor that is measuring tidal inundation at a fishpond makaha (water gate) located in the muliwai (estuary) where many species gather.

(Whitney Pandil-Eaton/USPTO)

“Prime” Hina, who painted the mural of Lagon’s mother at KPT, sees the connection.

“Gang activity and violence was prevalent (at KPT), but Olin came out of that with a heart of gold. That’s from his mom,” he said. “Olin can relate to so many people from the ground up. Everyone is equal in his eyes.”

It is through that connection to people and heritage that his particular brand of innovation emerges.

“Innovation has many flavors,” Lagon said. “I represent some of the traditional innovations like crowdfunding, but innovation is rooted in a lot of historical and indigenous innovations.”

He points to the 88-acre traditional Polynesian fishpond that sits at the connection of the Pacific Ocean and nearby streams on the southwest part of O’ahu. Surrounded on two sides with land and two with sea walls, the fishpond serves as a nursery for more than a dozen species including barracudas, eels, pufferfish, mantis shrimp, and sea worms. The mix of freshwater from the nearby stream and the salt water from the ocean encourages the production of algae, a food source for the nursery fish. A series of handmade traditional wooden gates allow small fish to enter the pond and feed, safe from predators.

With climate change, caretakers of this ancient fishpond are incorporating modern sensor technology to provide data points on salinity, turbidity, and tide among other metrics in concert with their traditional observational methods. The objective is to understand how the changing climate is affecting the fishpond and use scientific data and traditional ancestral knowledge to help native aquatic species thrive. This project is a collaborative effort between Purple Mai’a alum companies Hohonu, NRDS, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The Hikianalia, sister canoe to the famous Polynesian sailing canoe Hōkūleʻa, is being repaired before the pair leave for their next voyage. This 4-year expedition will see the canoes and their crew travel 43,000 nautical miles to visit nearly 100 indigenous tribes in 36 countries.

(Whitney Pandil-Eaton/USPTO)

Highlighting another revered cultural symbol, Lagon said he aspires to be like Hikianalia, a sister support canoe to the famous Hōkūleʻa, a traditional Polynesian sailing canoe that launched the Hawaiian cultural renaissance in the 1970s. He built the data system used on board by the land crew to track a variety of information sets. The Polynesian Voyaging Society, the nonprofit that maintains the canoes, is preparing the vessels for a four-year journey that will take them across the world visiting indigenous cultures to highlight the importance of the oceans, science, nature and traditional knowledge.

“I get so sick [on the boat] but I can imagine myself 600 years ago on the land asking, ‘what can I engineer for you?’” he said.

With his Na’au Pono (following your instinct for betterment of ourselves and the environment) firmly intact, Lagon looks for the next problem to solve.

“I love what I’m doing, and I probably have another four or five ventures left in me before I hang it up,” Lagon said.

He never innovates in the same industry, Lagon said, because many times “experts” will miss opportunities to innovate because they are stuck in that institutional mindset.

“When I jump into [a new industry], I’m coming at it with the wisdom of children, like everything is brand new and possible,” he said.

One industry that already has his attention: Housing.

Back at Purple Mai’a, he points to an open public greenspace across the street, explaining that the space is routinely used as a homeless encampment for many of the island’s nearly 4,000 unhoused persons.

“I would love to jump into helping on that challenge next,” he said.

Credits

Produced by the USPTO’s Office of the Chief Communications Officer. For feedback or questions, please contact inventorstories@uspto.gov.

Story by Whitney Pandil-Eaton. Additional contributions from Eric Atkisson, Jay Premack, and Jennifer McIntosh. Special thanks to Olin Lagon and family, the staff of Shifted Energy, Gloria Needs, the staff of Purple Mai'a, the Maglinti family, students and staff at Kamehameha Schools, John "Prime" Hina, and staff at the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

References

"800-year-old taro farming techniques revealed". February 4, 2021. University of Hawaii News. https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2021/02/04/800-year-old-taro-farming/

Hina, John "Prime". Interview by Whitney Pandil-Eaton. April 5, 2023.

"Hawaii Profile" Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/profiles/HI.html

Ignacio, Jennifer. Interview by Whitney Pandil-Eaton. April 19, 2023.

Lagon, Olin. Interview by Whitney Pandil-Eaton. Multiple between February and April, 2023.

Needs, Gloria. Interview by Whitney Pandil-Eaton. April 19, 2023.

Office of Minority Health. "Profile: Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2019. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=65#:~:text=T…

Partners in Care (O'ahu). "2022 Partners in Care Point-in-Time Count". U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. July 6, 2022. 2022+PIT+Count+Report+7.6.22.pdf (squarespace.com)

"Hawaii- history and heritage". November 6, 2007. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/hawaii-history-and-heritage-41645….

U.S. Energy Information Administration. "Hawaii State Energy Profile." March 2023. Hawaii Profile (eia.gov)