Driving innovation

Audrey Sherman was initially drawn to science by the appeal of "cooking polymers all day and driving a sports car," but it was her personal drive and persistent inquisitiveness that paved her way to becoming 3M's top female patent holder. Perhaps best known for inventing the adhesives on smartphone screen protectors and Command hooks designed for humid or soapy environments, Sherman is quick to credit the invaluable role collaboration has played in her success.

16 min read

Each month, our Journeys of Innovation series tells the stories of inventors or entrepreneurs who have made a positive difference in the world. Hear it in their own words or read the transcript below.

Audrey Sherman: And I was like, "You guys, this is incredible. You have put my polymer now, that I cooked, on a sports car, on a Lamborghini in this mirror finish." And it just, I mean, that thing looked fabulous.

Marie Ladino: Inventor Audrey Sherman used to dream of being a scientist who created polymers and drove a sports car. Her "full circle patent," as she calls it, is for the adhesive that gave a Lamborghini a mirror-like finish without causing corrosion. The patent is one of 150 Sherman now holds for inventions including the adhesives on smartphone screen protectors and on Command hooks designed for warm, wet environments. It's also an example of the crucial role teamwork has played in her success.

I'm Marie Ladino from the United States Patent and Trademark Office. I recently spoke to Sherman about her achievements at 3M, her advice for other innovators, and the benefits of collaboration and diversity to innovation. Here's a bit of our conversation.

Be brave, because you don't have to know the answer. You're going to find the answer.

Marie Ladino: Can you tell me a little bit about your current job and some of the projects you're working on?

Audrey Sherman: In the Medical Solutions Division, I'm working on a whole host of medical devices, as you could imagine. So it ranges from coatings on stethoscopes that could give us opportunities to personalize them, all the way to sterilization indicators and how we can better improve that manufacturing process. It would be wonderful if every manufacturing line in the company ran with zero waste, and that's just not true today. But I'm working on ways that we will be able to improve it and go a lot more toward that entitlement. And then there's always wound dressings and tapes, which is my very, very favorite area to work in.

Marie Ladino: So was there a person or an experience that first got you excited about science and technology when you were a child?

Audrey Sherman: I have a sister who's about three years younger than I, and we used to mix up whatever we could find in the bathroom, in the bathroom sinks. A lot of it was soaps and shampoos and probably some of my mom's things that were in there, too. And our mother never once got after us for doing that. She was just really great about allowing us to make these magic formulas, which really never really did anything, except I just remember her saying, "It's okay, because when you guys are done, you know, just clean up." And since there was a lot of soaps and shampoos, it was really clean all the time. So I have to say early on it was my mother. She just, she let me take apart things and learn how to put them back together again. I was my dad's best flashlight holder in the whole family. Of him working on something, I wanted to be there to hold the flashlight and watch everything that he was doing. So my parents just really let me be curious, and that curiosity just has never left me.

Marie Ladino: I understand you started working at 3M in high school. Tell me how that opportunity came about.

Audrey Sherman: 3M has a program called Science Training Encouragement Program, and it's actually over 45 years now that they've been doing it in the high schools that are nearby the center here in Minnesota. And they sent three scientists into our 11th-grade chemistry class to talk about what a career in science looks like, and also introduce you to their program. And there was a woman there, and she described it that she cooked polymers all day and drove a sports car. And I was just like, "Okay, that's it. That's my, that is going to be my job." I was just hooked right from there. This was the beginning, the fall of our chemistry class. I mean, we still didn't know what a molecule or an atom was, and here she was using the word "polymer." And I was just like, "Ah, I gotta have that," and ended up joining the program and working with her that summer as my full-time job, still without my driver's license. But luckily, her house and my house, they were on the way to 3M Center. So I got to ride in the sports car every day to go to work with her.

Audrey Sherman began her career at 3M when she was still in high school. She joined one of the company's softball teams and participated in an all-star game at Tartan Park Baseball Field in Lake Elmo, Minnesota, in June of 1982. In the above photo, she poses in her "Batwomen" uniform in the front row, second from left.

Marie Ladino: The 3M scientist who sparked Sherman's curiosity and livened up her commute also became her first mentor. She explained how influential mentors have been throughout her career.

Audrey Sherman: Mentors are, in my career, have been really, really important. It's the mentors that I was exposed to who got to talk to me about even just picking out colleges, and the mentors even that helped me buy my first sports car—so that when I came back senior year and I had my license and I had my sports car—to the mentors that helped me throughout my career as well, especially being a woman in the field of science. I've been there over 35 years now. And honestly, way back when, there was just me and all the guys, but they were like my brothers, and we helped each other. And we talked about how you could move your career here and there. And they were very interested in what I wanted to do, and that's a great mentor. They're there to help you and lift you up. And they can't make the decision for you, but they lay out all the options, and things you hadn't thought of appear. Having those different points of view is so useful as you're moving up in your career. You need to find those big brothers and big sisters who are going to be able to look at you from a different angle. It's wonderful.

Marie Ladino: How do you encourage the people who you mentor?

Audrey Sherman: I reach back into my own history and tell them an actual story of this is what happened to me. And it works out really well because they can either see it from a different way, or they can maybe see myself struggling and how I was doing it in my shoes, and see that, no, you don't always know the answer. Some of it, you're just feeling along the bottom of the room to find out which way you need to go and which door to go into. And so through those stories, when they're able to see an ending, an outcome, I think that's so helpful. You're just not lost anymore.

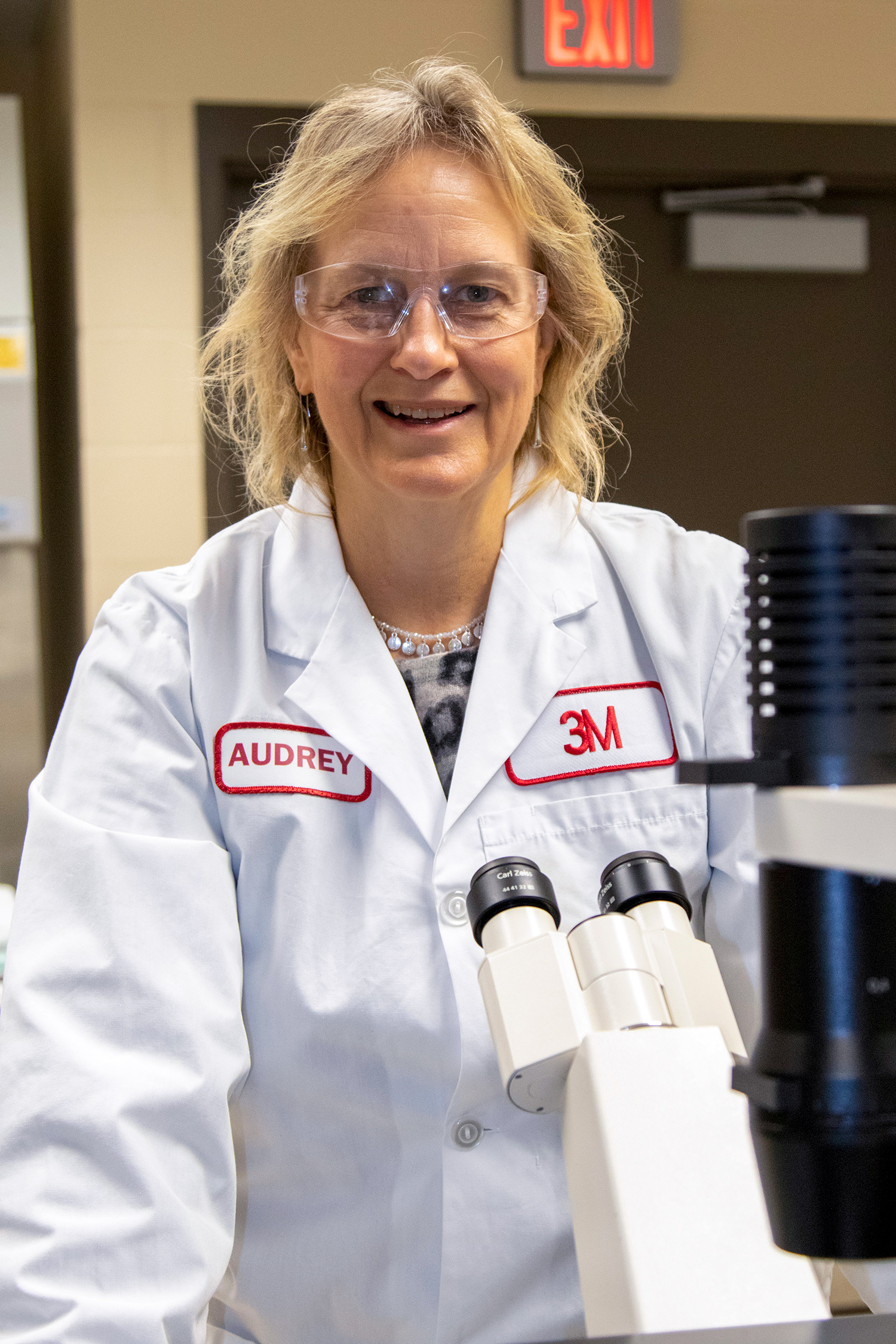

As an inventor of adhesives, Audrey Sherman has contributed to the creation of sticky tape used for wrapping presents and pain-free, easily removable medical tape for diabetics. The photo above captures Sherman at work in the 3M Medical Lab in November of 2019.

Marie Ladino: Sherman has a story, along with a recognition plaque from 3M, to accompany each of her patents, which now total 150. This incredible achievement makes her 3M's top female patent holder and the current employee with the second-highest number of patents. She's also named on 3M's 100,000th patent. She shared with me what made these extraordinary accomplishments possible.

Audrey Sherman: Of my 150 patents, two are just singly in my name. So 148 are with co-inventors. There are over 200—not double-counting anyone—co-inventors with me. I look at science and invention really as a team sport. And so I did make it a goal when I first started filing IP [intellectual property] with the company to work with a lot of people who knew a lot more than I did when I first started out about patents. And I just went to them and said, "How can I help you?" And we figured out a way to do something and then got filing a patent. And now, I'm the one at the other end, saying to everyone, "You need to help me. We need to invent something together. We haven't done anything together. You and I are going to come up with something that nobody else could ever think of because they are not you, and they are not I. And actually, if we add four more into the mix—wow—that's going to be really incredible." The more diversity we bring in, and the more creativity, the better, and so it just works.

Marie Ladino: Why was it important to receive patents for your inventions?

Audrey Sherman: The patent doesn't mean that you can do it. It means that others can't do it. So that exclusivity for a company allows us the time that's needed to get through all of the processes that we have to do to bring a product to market. No factory output is ever at full efficiency, and it takes a lot of time to do that. So you need to be able to have that time to yourself. And that's what a patent affords you: the time to yourself with that claim set, so that you can bring it to market and bring out the best product that you can.

Marie Ladino: Tell me about the recognition plaques 3M gives when you receive a patent.

Audrey Sherman: 3M does that for each patent earner, so that the management has something to hand out to acknowledge this accomplishment. And so I used to see them all over the place. Some of the inventors have them on their walls, in their office. Some of them have them down the halls, and some of them just have the boxes they come in, with the plaques still inside, stacked up in the corner of their office. And I decided I am not going to do that. And it was my husband who said, "What are you going to do with these?" And we moved into a new house, and if you can imagine, you walk up the stairwell—well, behind you on the stairwell, there's just nothing. There's just big walls. And so we decided, oh, we're going to just put them in there. And so we designed a way, just like plates on a shelf, to have these rails that we just slide them in, and we could fill up that whole wall. We got 123 there right now, and there's actually no more room for any more on that area. I never thought this. We planned it at 100, and then we had to hack it off and make it bigger for the 23. So now, luckily, I have another staircase in the house. So we're eye-balling that one to see if we can display them there. It's very, very subtle, but it makes such a statement. It's just incredible to see them all there together.

Marie Ladino: When people come to your house and see those plaques, how do they respond?

Audrey Sherman: I think most people, they understand what a patent is and an invention. And I think when they see them, they just, first of all, they want to know a story. So they're not arranged numerically either. They're arranged by who I invented with, which is really cool. And so I do have a story with them. The ones that are very low, that we can see, I talk about it to them. And they are just amazed at how varied they are. And that is just from my experience in the number of people that I invent with—from optics, to adhesives, to things that don't stick, to duct tape and Command hooks and masking tape.

Marie Ladino: Is there an invention you're especially proud of?

Audrey Sherman: One of my favorite inventions is the—for the shower and bath—the Command hook. Command hooks were already known, and the customer wanted to put them in the shower, and they wanted to hang the teeniest thing. They wanted to hang a ladies' razor. It weighs 20 grams, if that, but the Command hooks wouldn't work, and they didn't want to use—like everyone—a suction cup. So the company put a big search out for whose adhesive could hold things when they were wet and soapy, and also keep the Command brand of stretching and coming off clean. And so participating in that and submitting the adhesive that I had, that I was working on at the time to stick pavement marking down to wet roads, turned out to be the one that worked, and it was just fabulous. It was the first time that 3M ever commercialized an adhesive along that class of materials, too. And they still use it today. And so that one is really my favorite one because I use that adhesive everywhere, because if it can go in the shower, I actually know it can also go on my dry wall or on my window, too. And so I just use that one all the time.

On December 25, 2018, Audrey Sherman and her 3M co-inventors received U.S. Patent No. 10,162,090 B1 for a "conformable reflective film having specified reflectivity when stretched at room temperature." Sherman's experience developing adhesives that didn't cause corrosion was essential in creating this film, which the team designed to give the Lamborghini a mirror-like finish. The car went on display at 3M headquarters in St. Paul, Minnesota, in February of 2019.

Marie Ladino: I also have to ask you about the Lamborghini project.

Audrey Sherman: So my full circle patent is—remember wanting to cook polymers all day and drive a sports car? Well, a group in my company wanted to wrap a car, a Lamborghini, with their mirror wrap. So it's their graphic film that's actually a mirror finish. And they were having some problem finding the adhesive that wouldn't corrode that wrap. And so they called me up, and they said, "We remember that you worked on this years ago, and what was it? And it didn't corrode." And I said, "Yes, this is great. Here's what it is. Call this guy. Get a bucket of it. It will do what you guys have asked it to do." And then I did not hear from them for maybe even half a year until they said, "By the way, it works. We're filing on it. You're the one who told us this is the adhesive, so you have to be on the patent. It was your contribution to the claim." And I was like, "You guys, this is incredible. You have put my polymer now, that I cooked, on a sports car, on a Lamborghini in this mirror finish." And it just, I mean, that thing looked fabulous. I never got to sit in it or drive it, but I'll tell you right now, that thing is an amazing looking sports car with my polymers stuck on it.

Audrey Sherman recently hosted Miss America 2020, Camille Schrier, at 3M headquarters in St. Paul, Minnesota. Schrier is a biochemist and was the first person to demonstrate a science experiment in the talent segment of the pageant. Sherman emphasizes the importance of female role models in STEM fields, saying, "If you can see that it's possible, then maybe you can start to see yourself in those shoes."

Marie Ladino: This patent illustrates how far Sherman has come since her introduction to chemistry in high school and her first dreams of being a scientist and driving a sports car. Throughout her 35-year career at 3M, she's learned many important lessons, and she offers encouraging advice for students interested in STEM careers.

Audrey Sherman: Science gives you the ability to ask questions. Science isn't about knowing the answers. You've got to get that straight. It's not about knowing the answers. It's about finding the answers. And so when I work with students that come to work for me, I tell them this one thing: We're doing this experiment not so we can look at the back of the book and check the answers with the odd numbers. We don't know what the answer is. When you're done with the experiment, we're going to have the answer. And actually, until you tell me what happened with the experiment, you're going to be the only one in the world who knows what that answer is. And that's just super powerful. It doesn't mean that you have to know what to do with the answer. That's different. Science is looking for answers. The group part of it, where we play this as a team, is when everybody comes together and says, "What are we going to do with these answers?" And I just think that in order for that group to come together for the "what will we do," we need to have all kinds of diverse ideas, or it's just stuck, and you can't move it forward. So I would say, "Be brave, because you don't have to know the answer. You're going to find the answer." And then it's just so much fun to work in such a group and go back and forth and communicate with each other, and just, you really build off of each other.

Marie Ladino: Given your own experiences, what advice would you offer other innovators, and especially women?

Audrey Sherman: You have to be able to speak for yourself, find advocates as well. One of the upper management, when they were congratulating me for 150, said, "One thing about Audrey is when she knows she's right, she will never stop." And that's absolutely true. When I know that this is the right thing, I really am not going to stop. I'm just going to keep pestering them. And, you know, it's okay. It's okay, because in my mind, they just don't see it yet. It's my job to make sure they see what I see. And I think that is really important for female innovators and inventors that they're not—just remember, they're not seeing it how you saw it. And maybe, they possibly can't even see it how you saw it because you're so unique in how you think. But it's your responsibility to make sure they do, and don't stop until they do.

Marie Ladino: I heard you speak recently as part of DiscoverE's Persist series, and you talked about your philosophy of throwing a rope down. Can you share a little bit with this audience about what that means?

Audrey Sherman: Throwing the rope down is really about giving back to help others rise up to your level. The first thing that's really nice is to get out there and let people see what's possible. Okay, so if you can see that it's possible, then maybe you can start to see yourself in those shoes. "Hey, she could do this. Maybe I can do this." And so the second portion of that is, once they see that and women have this view that it's possible, we—other women—we owe it to them to help. You absolutely owe it to them to help. Help them up. Lift them up with you. Bring them along for the journey. You know, I do it in IP with just targeting questions: "I'd like to know, what do you think about this?" And all of a sudden, they'll come back with something I hadn't thought of. And it's like, "You need to write that down. That is going to be in a claim because I didn't think of it. You did." Now, you could just simply never ask. That is not throwing the rope down. You need to actively take part with helping the other female scientists. And we can do that. It's easy.

Marie Ladino: Audrey Sherman has set a strong example for others as a passionate inventor, innovator, and mentor. And there's still much more to come from this outstanding scientist. Her constant enthusiasm shows in her work, and her influence is reflected in everyone inspired by her journey.

From the USPTO, thanks for listening.

Credits

Produced by the USPTO Office of the Chief Communications Officer. For feedback or questions, please contact inventorstories@uspto.gov.

Interview and story production by Marie Ladino. Audio editing by and contributions from Jay Premack. Additional contributions from Lauren Emanuel. All images are courtesy of 3M. The images at the top of the story page and on the USPTO homepage show Audrey Sherman at home in her stairwell surrounded by the plaques 3M gave her to commemorate her patents.

The transcript has been edited for brevity.