Since the passage of the first Patent Act of 1790, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO)* has figured into an expansive list of interesting historical factoids. One is the origin of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The United States was founded on an agricultural economy. At the time, over 75 percent of the nation’s exports were agricultural products. It was apparent to the first four presidents (all farmers) that a strong economy depended on having an innovative agricultural industry, and they called for the establishment of a department of agriculture to foster improved farming practices and technologies. Congress did not, however, act on their recommendations. At the time, many Americans were economically independent farmers who had just fought the Revolutionary War to guarantee their self-determination. The challenge in creating the new nation was how strong to build the central government. Many farmers believed that a centralized department of agriculture would become too powerful and control their lives (Hagenstein et al., 2011).

By the 1830s, significant agricultural problems stressed the economic health of the nation. Standard farming had left a substantial amount of land in the Eastern states unproductive due to pests, diseases, and lack of fertilization. There was a need for a systematic collection and distribution of information on farming practices, as well as new and improved cultivars that could thrive and produce better harvests. To address these needs, Congress established the Agricultural Division within the Patent Office in 1839.

The decision to designate the Patent Office for oversight of agricultural improvements was advocated strongly by the Commissioner for Patents at the time, Henry Leavitt Ellsworth. In an 1838 report to Congress, he had written that “the Patent Office is crowded with men of enterprise, who, when they bring the models of their improvements in such implements, are eager to communicate a knowledge of every other kind of improvement in agriculture, and especially new and valuable varieties of seeds and plants.” He described at length the benefits of specific cultivars developed by farmers or collected by travelers, particularly members of the Navy, in foreign countries and sent to the Patent Office. Congress was convinced. The mission of the Agricultural Division would be to acquire, propagate, evaluate, and distribute seeds and plants to farmers, and to collect agricultural statistics and production information.

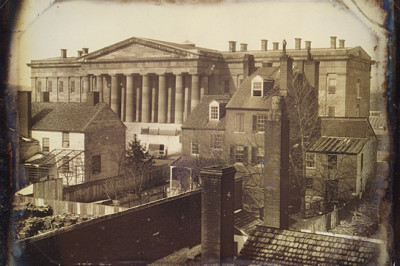

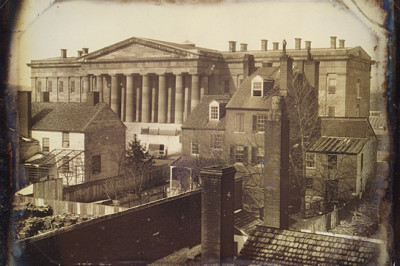

The grounds around the Patent Office were used as the garden to grow the nation’s living plant collection. For plants that were not winter-hardy in the Washington, D.C., area, two 50-foot long greenhouses were constructed (Weber, 1924). In 1849, however, the land that the greenhouses and garden occupied was needed for an expansion of the Patent Office Building. Congress appropriated $5,000 to relocate the greenhouses and garden to a site on the National Mall just west of the Capitol. This new and improved garden opened in 1856 and was known as the U.S. Propagation Garden (Holt, 1858).

By the 1860s, the Agricultural Section of the Patent Office was annually distributing over 2.4 million packages of seed from the basement of Patent Office Building. In 1864, Lois Bryan Adams, an Agricultural Division employee, news correspondent, and one of the first women employed by the federal government, described the basement area in a dispatch to the Detroit Advertiser and Tribune:

“Before us is a room 50 feet long by 25 feet wide; down the center nearly the whole length extends a table, on each side of which sit women and girls, forty in number, gray-haired, middle-aged, and youth scarcely past childhood, all closely crowded together, and bent over the work of filling and stitching up the piles of little seed bags before them. Between these busy workers and the wall, on either side, in rows three deep, stand casks and barrels, and piled upon these are other barrels, sacks, and boxes, containing seed prepared, or to be prepared, for distribution by mail or express to country homes far away.”

The Civil War demonstrated that the government needed to be more involved in advancing agriculture and addressing agricultural issues. Science was beginning to play a major role in agricultural production. For example, the scientific study of fertilizer resulted in the discovery that nitrogen was an essential plant nutrient.

In order to advance science-based agriculture, President Abraham Lincoln and Congress established the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 1862. The Commissioner of Agriculture was authorized “to receive & have charge of all property of the Agricultural Division of the Patent Office including fixtures & property of Propagating Garden” and to appoint a statistician, chemist, entomologist, and botanist. The statistician, chemist, and entomologist in the Agriculture Division of the Patent Office were retained and became employees of the USDA. Isaac Newton was appointed the Commissioner of Agriculture and he appointed William Saunders as the botanist.

Despite its autonomy, the newly founded USDA was still housed in the basement of the Patent Office, which it quickly outgrew along with the U.S. Propagation Garden. In 1868, the USDA moved into its own building on 20 acres just east of the Washington Monument. John Ellis (1869) described the Agricultural Building’s offices and laboratories in detail:

“The basement is well lighted, and contains, besides furnace and stove rooms, a laboratory and folding rooms. Upon the first floors are the offices, the library, and a second laboratory for the lighter work ... Upon the second floor is the main hall, fitted up with massive walnut cases, made air-tight, for the specimens which compose the museum ... On this same floor are rooms in which work connected with preparing specimens is done, and also the Statistical Bureau of the Department … The fourth floor, which is immediately under the roof, extends over the whole building, and resembles in all respects a great grain warehouse. An elevating platform connects it with the basement, and gives an easy method of raising the supplies of seed-grain, which are kept in this thoroughly dry and well ventilated space.”

Today, the USDA continues its important work to propagate and disseminate better farming practices and cultivars. Plants developed by the USDA can be found in supermarkets across the country, from blueberries to peppers and soybeans, but it all took root at the USPTO, over 150 years ago.

*Though the 1790 Patent Act established a federal patent system, an autonomous Patent Office is not considered to have begun until 1802 with the appointment of its first full-time employee, Dr. William Thornton. The designation “Patent and Trademark Office” was not instituted until 1975.

References

Adams, L.B. 1863. Life in Washington. Detroit Advertiser and Tribune, Dec. 1, 1863. p. 2.

Adams, L.B. 1864. The government propagating garden. Detroit Advertiser and Tribune, Feb. 5, 1864. p. 4.

Capron, H. 1868. Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. p. 1-14.

Ellis, J.B. 1869. The Sights and Secrets of the National Capital. U.S. Publishing Co., New York. p. 351-357.

Hagenstein E.C., S.M. Gregg, and B. Donahue. 2011. American Georgics. Yale Univ. Press.

Holt, J. 1858. Report of the Commissioner of Patents, Agriculture. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. p. 3-7.

True, A.C. 1937. A history of agriculture experimentation and research in the United States. U.S.D.A. Misc. Publ. 251. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. p. 42-43.

Weber, G.A. 1924. The Patent Office: Its History, Activities and Organization. Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, MD.

Weber, G.A. 1924. The Patent Office: Its History, Activities and Organization. Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, MD.

The USPTO gives you useful information and non-legal advice in the areas of patents and trademarks. The patent and trademark statutes and regulations should be consulted before attempting to apply for a patent or register a trademark. These laws and the application process can be complicated. If you have intellectual property that could be patented or registered as a trademark, the use of an attorney or agent who is qualified to represent you in the USPTO is advised.