“A day will come, when, in the eye of the law, literary property will be as sacred as whiskey, or any other of the necessaries of life.” — Mark Twain, speech in Montreal, Quebec, 1881.

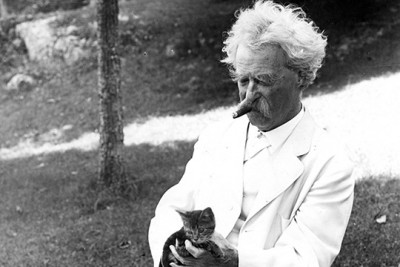

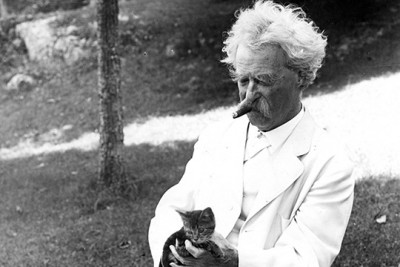

The popular image of Mark Twain is that of an old man with wild white hair, flaring eyebrows and mustache, grasping a cigar, standing resplendent in a white suit. But Samuel Langhorne Clemens did not adopt that celebrity look until 1906, when he was 71 years old. By the strictures of men’s fashion, white flannel was reserved for summertime and verandas. But this was a windy December day, and the setting was a Congressional hearing on copyright legislation.

It was a dramatic unveiling. Clemens removed his overcoat in a sea of black and grey suits. “Resplendent in a White Flannel Suit, Author Creates a Sensation,” read the headline in the New York Tribune. Always quick to promote himself, Clemens ordered more of such suits, saying they displayed the purity of his motives as a lobbyist.

He was lobbying for intellectual property rights, a concept that was fighting the tradition that an author was at the mercy of a publisher when it came to making money from his or her work. He was also fighting a long tradition of literary piracy.

In 1867—39 years before he put on that suit—the author first published his wildly popular short sketches, including his reputation-making “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.” He found that unscrupulous publishers were pirating his work, plucking short funny pieces he had written for newspapers and putting them into books. (In one such case, the judge held for the pirate, as the articles hadn’t been copyrighted and the publisher gave Clemens credit as “Mark Twain.”)

But even when his work fell under U.S. copyright protection, publishers in the other English-speaking countries that loved his work—notably Canada and the United Kingdom—were reaping tremendous profits from his books without a thought to including Clemens himself in the take. He said of one British publishing pirate: “I feel as if I wanted to take a broom-straw & go & knock that man’s brain out. Not in anger, for I feel none. Oh! Not in anger; but only to see, that is all. Mere idle curiosity.”

Canadian publishers in particular could publish cheap editions and export them easily to the United States, undercutting the editions for which Clemens was receiving royalties. He traveled to Canada on several occasions to establish residency in time for the publication of his books. British law provided for copyright protection as long as a book was published in England first; he traveled to England in 1873 to ensure that "The Gilded Age"—the novel he co-authored with Charles Dudley Warner that gave a name to the era—came out there two days before it came out in America, and "Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" was published in London in December 1884 and in the United States in February 1885.

When he became a publisher himself for a time, he warned his nephew and partner in the business, Charles W. Webster, against north-of-the border thieves, specifically regarding "Huckleberry Finn." “You want to look out for the Canadian pirates,” he wrote a few months before publication. “They could play the mischief with us now, if they should beat us out a month or two with this book. They will try.” And later, when his company was preparing to bring out the "Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant," he wrote: “Stop leaving those proofs on your table—keep them always in your safe. From now until the day of issue, the Canadian emissary will be around (how do you know but you’ve got him in your own employ) seeking to buy or steal proofsheets.”

In 1885 Clemens’s Hartford, Connecticut, neighbor, Senator Joseph Roswell Hawley, introduced a bill that would extend copyright protection to foreign authors—another aspect of the issue that American authors believed would protect them from being undercut by foreign publications. The bill ultimately failed, but not before Clemens, who had testified in its favor before the Senate Committee on Patents, had enlisted the aid of President Grover Cleveland. Clemens wrote the president: “Although a most worthy cause has failed once more we who are interested have one large consolation: that the country has at last had a resident who appreciated its importance.”

In 1900 Clemens actually appeared before a committee of Britain’s House of Lords to testify in favor of copyright protection, as he told the story later during his 1906 “white suit” speech:

"When I appeared before that committee of the House of Lords the chairman asked me what limit I would propose. I said, "Perpetuity." I could see some resentment in his manner, and he said the idea was illogical, for the reason that it has long ago been decided that there can be no such thing as property in ideas. I said there was property in ideas before Queen Anne's time; they had perpetual copyright. He said, "What is a book? A book is just built from base to roof on ideas, and there can be no property in it." I said I wished he could mention any kind of property on this planet that had a pecuniary value which was not derived from an idea or ideas."

By December 1906, Clemens was willing to settle for less than perpetuity. Speaking in his glowing garb before the Committee on Patents of the Senate and the House, he hoped to see the 42-year copyright period extended “to the author's life and fifty years afterward.”

Indeed, by this time he was thinking seriously about what he would leave his own children. His wife had died two years before, and he was keenly aware that his earliest books were nearing the 42-year limit decreed by copyright law. His two surviving daughters—Clara, 32 years old, and Jean, 26—might lose out on the royalties from these early works. Seeking a laugh (and he got many that day), he said that the two young women “can't get along as well as I can because I have carefully raised them as young ladies, who don't know anything and can't do anything.” (This was a blatant untruth. Among other things, Clara was an accomplished concert singer; Jean an animal rights activist and woodcarver. Their reaction to their father’s joke is not recorded.)

But he progressed to a tone of seriousness, seasoned, as always, with wit:

"I am interested particularly and especially in the part of the bill which concerns my trade. I like that extension of copyright life to the author’s life and fifty years afterward. I think that would satisfy any reasonable author, because it would take care of his children. Let the grand-children take care of themselves. That would take care of my daughters, and after that I am not particular. I shall then have long been out of this struggle, independent of it, indifferent to it."

Four years later, in 1910, Clemens was out of the struggle. By then he had seen and praised the passage of the Copyright Act of 1909, which allowed for renewal of copyright, bringing it to a total of 56 years. It was not until 1976 that American authors were finally granted Mark Twain’s “life and fifty years afterward.”

♦

Steve Courtney is a Curatorial Consultant at The Mark Twain House & Museum in Hartford and the author of "Joseph Hopkins Twichell: The Life and Times of Mark Twain’s Closest Friend" (Georgia, 2008) and “'The Loveliest Home That Ever Was': The Story of the Mark Twain House in Hartford" (Dover, 2011).

The USPTO gives you useful information and non-legal advice in the areas of patents and trademarks. The patent and trademark statutes and regulations should be consulted before attempting to apply for a patent or register a trademark. These laws and the application process can be complicated. If you have intellectual property that could be patented or registered as a trademark, the use of an attorney or agent who is qualified to represent you in the USPTO is advised.